(Press-News.org) Two to three weeks after conception, an embryo faces a critical point in its development. In the stage known as gastrulation, the transformation of embryonic cells into specialized cells begins. This initiates an explosion of cellular diversity in which the embryonic cells later become the precursors of future blood, tissue, muscle, and more types of cells, and the primitive body axes start to form. Studying this process in the human-specific context has posed significant challenges to biologists, but new research offers an unprecedented window into this point in time in human development.

A recent strategy to combat these challenges is to model embryo development using stem cell technologies, with many valuable approaches emerging from research groups across the globe. But embryos don’t grow in isolation and most previous developmental models have lacked crucial supporting tissues for embryonic growth. A groundbreaking model that includes both embryonic and extraembryonic components will allow researchers to study how these two parts interact around gastrulation stages—providing a unique look at the molecular and cellular processes that occur, and offering potential new insights into why pregnancies can fail as well as the origins of congenital disorders. The team, including Berna Sozen, PhD, and Zachary Smith, PhD, both assistant professors of genetics at Yale School of Medicine (YSM), published its findings in Nature on [tk].

“This work is extremely important as it provides an ethical approach to understand the earliest stages of human growth,” says Valentina Greco, PhD, the Carolyn Walch Slayman Professor of Genetics at YSM and incoming president-elect of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), who was not involved in the study. “This stem cell model provides an excellent alternative to start to understand aspects of our own early development that is normally hidden within the mother’s body.”

“The Sozen and Smith groups have achieved a milestone in developing in vitro models to study the earliest stages of human development that are unfeasible yet so important for understanding health and disease,” says Haifan Lin, PhD, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Cell Biology, director of the Yale Stem Cell Center, and president of ISSCR. “I commend their exceptional accomplishment as well as their sensitivity to ethical issues by limiting the model’s ability to develop further”

The ethical questions are profound, including whether these models have the potential to develop into human beings. Sozen, the principal investigator of the study, emphasizes that they do not. The published paper demonstrates that this model lacks trophectodermal cells, which are required for an embryo to implant in the uterus. Sozen says this model also represents a developmental stage beyond the time frame in which embryos can implant. “It is very important to focus on the fact that our model cannot grow further or implant and therefore is not considered a human embryo,” she says. But as a reductionist strategy to mimic and study aspects of natural development, its potential is immense, especially where universal guidelines severely limit scientists’ ability to study actual embryos.

New Model Contains Embryonic and Extraembryonic Tissues

All embryos have two components—embryonic and extraembryonic. The tissues we have now in our adult bodies grew from the embryonic component. The extraembryonic component includes the tissues that offer nutritional and other support, such as the placenta and yolk sac. The majority of previous embryo models of developmental stages around gastrulation were single-tissue models that only contained the embryonic component.

In the new study, the Yale-led team grew embryonic stem cells in vitro in the lab to generate their new model. They transferred these cells into a 3D culture system and exposed them to a conditions which stimulated the cells to spontaneously self-organize and differentiate. The cells diverged into two lineages—embryonic and extraembryonic precursors. The extraembryonic cells in this model were precursors for the yolk sac. The researchers grew these cellular lineages in the culture for approximately one week and analyzed how they guided each other as they developed. “We started looking into very mechanistic details, such as what signals they are giving each other and how specific genes are impacting one another,” says Sozen. “This has been limited in the literature previously.”

The Need for Models of Human Development

While researchers have learned a great deal from embryos of other species such as mouse, the lack of accessibility to human embryos has left significant knowledge gaps about our development. “If you want to understand human development, you need to look at the human system,” says Sozen. “This work is really important because it’s giving us direct information about our own species.” Not only does this model give access into the human gastrulation window, but will also allow for a greater quantity of research. The ability to generate as many as thousands of these models will allow for mass analysis that is not possible with human embryos. “I’m one scientist with one vision,” says Sozen. “But thinking about what other scientists are envisioning globally and what we can all accomplish is just really, really exciting to me.”

The new model has over 70% efficiency—in other words, the stem cells aggregate correctly over roughly 70% of the time. As noted by the authors, there are some limitations to the strategy, and it is challenging to benchmark some findings against the natural embryo itself. Sozen hopes to continue to work on the models so that they become more standardized in the future.

The team believes the models will transform scientists’ knowledge around human developmental biology. In their latest publication, the team explored some of the molecular paths underlying human gastrulation onset. In future studies, they hope to delve even deeper into the developmental pathways, including whether pregnancy loss and congenital disorders may stem from failures during gastrulation stages. Sozen believes her model can be used to look at some of these disorders and learn more about what is going awry. “Previous model systems have been able to look at this, but our model is unique because it has this extra tissue that allows us to analyze a bit deeper,” she says.

END

New model provides unprecedented window into human embryonic development

2023-06-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Deaf mice can have virtually normal auditory circuitry: implications for cochlear implants

2023-06-27

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University, US, led by Calvin Kersbergen report that mice with the most common form of human congenital deafness develop normal auditory circuitry – until the ear canal opens and hearing begins. Publishing June 27th in the open access journal PLOS Biology, the study suggests that this is possible because spontaneous activity of support cells in the inner ear remains present during the first weeks of life.

Mutations to the protein connexin 26 are the most common cause of hearing loss at birth, accounting for more than 25% of genetic hearing loss worldwide. To understand how these mutations lead to deafness ...

Deaf mice have nearly normal inner ear function until ear canal opens

2023-06-27

**EMBARGOED TILL TUESDAY, JUNE 27, AT 2 P.M. ET**

For the first two weeks of life, mice with a hereditary form of deafness have nearly normal neural activity in the auditory system, according to a new study by Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists. Their previous studies indicate that this early auditory activity — before the onset of hearing — provides a kind of training to prepare the brain to process sound when hearing begins.

The findings are published June 27 in PLOS Biology.

Mutations in Gjb2 cause more than a quarter of all hereditary forms of hearing loss at birth in people, according to some estimates. The connexin 26 protein coded by ...

Chemists are on the hunt for the other 99 percent

2023-06-27

The universe is awash in billions of possible chemicals. But even with a bevy of high-tech instruments, scientists have determined the chemical structures of just a small fraction of those compounds, maybe 1 percent.

Scientists at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) are taking aim at the other 99 percent, creating new ways to learn more about a vast sea of unknown compounds. There may be cures for disease, new approaches for tackling climate change, or new chemical or biological threats lurking in the chemical universe.

The work is part of an initiative known as m/q or “m over q”—shorthand ...

Easier access to opioid painkillers may reduce opioid-related deaths

2023-06-27

Increasing access to prescription opioid painkillers may reduce opioid overdose deaths in the United States, according to a Rutgers study.

“When access to prescription opioids is heavily restricted, people will seek out opioids that are unregulated,” said Grant Victor, an assistant professor in the Rutgers School of Social Work and lead author of the study published in the Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment. “The opposite may also be true; our findings suggest that restoring easier access to opioid pain medications may protect against fatal overdoses.”

America’s opioid crisis has ...

Fear of being exploited is stagnating our progress in science

2023-06-27

Science is a collaborative effort. What we know today would have never been, had it not been generations of scientists reusing and building on the work of their predecessors.

However, in modern times, academia has become increasingly competitive and indeed rather hostile to the individual researchers. This is especially true for early-career researchers yet to secure tenure and build a name in their fields. Nowadays, scholars are left to compete with each other for citations of their published work, awards and funding.

So, understandably, many scientists have grown unwilling ...

New findings on hepatitis C immunity could inform future vaccine development

2023-06-27

A new USC study that zeros in on the workings of individual T cells targeting the hepatitis C virus (HCV) has revealed insights that could assist in the development of an effective vaccine.

Every year, hepatitis and related illnesses kill more than one million people around the world. If unaddressed, those deaths are expected to rise—and even outnumber deaths caused collectively by HIV, tuberculosis and malaria by 2040.

For that reason, the World Health Organization and other leading groups have pledged to work toward eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030. While there are vaccines for two of the three most common ...

Cooperation between muscle and liver circadian clocks, key to controlling glucose metabolism

2023-06-27

Collaborative work by teams at the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS) at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), University of California, Irvine (UCI), and the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) has shown that interplay between circadian clocks in liver and skeletal muscle controls glucose metabolism. The findings reveal that local clock function in each tissue is not enough for whole-body glucose metabolism but also requires signals from feeding and fasting cycles to properly maintain glucose levels in the ...

Bias in health care: study highlights discrimination toward children with disabilities

2023-06-27

Children with disabilities, and their families, may face discrimination in in the hospitals and clinics they visit for their health care, according to a new study led by researchers at University of Utah Health. These attitudes may lead to substandard medical treatment, which could contribute to poor health outcomes, say the study’s authors.

“They mistreated her and treated her like a robot. Every single time a nurse walked in the room, they treated her like she was not even there,” said one mother who was interviewed about her child’s health care encounters.

The findings, published in the journal Pediatrics, ...

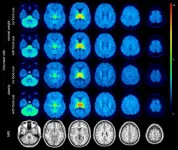

Molecular imaging identifies brain changes in response to food cues; offers insight into obesity interventions

2023-06-27

Chicago, Illinois (Embargoed until 10:05 a.m. CDT, Tuesday, June 27, 2023)—Molecular imaging with 18F-flubatine PET/MRI has shown that neuroreceptors in the brains of individuals with obesity respond differently to food cues than those in normal-weight individuals, making the neuroreceptors a prime target for obesity treatments and therapy. This research, presented at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2023 Annual Meeting, contributes to the understanding of the fundamental mechanisms underlying obesity ...

Flexible, supportive company culture makes for better remote work

2023-06-27

The pandemic made remote work the norm for many, but that doesn’t mean it was always a positive experience. Remote work can have many advantages: increased flexibility, inclusivity for parents and people with disabilities, and work-life balance. But it can also cause issues with collaboration, communication, and the overall work environment.

New research from the Georgia Institute of Technology used data from the employee review website Glassdoor to determine what made remote work successful. Companies that catered to employees’ interests, ...