(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Flexible displays that can change color, convey information and even send veiled messages via infrared radiation are now possible, thanks to new research from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Engineers inspired by the morphing skins of animals like chameleons and octopuses have developed capillary-controlled robotic flapping fins to create switchable optical and infrared light multipixel displays that are 1,000 times more energy efficient than light-emitting devices.

The new study led by mechanical science and engineering professor Sameh Tawfick demonstrates how bendable fins and fluids can simultaneously switch between straight or bent and hot and cold by controlling the volume and temperature of tiny fluid-filled pixels. Varying the volume of fluids within the pixels can change the directions in which the flaps flip – similar to old-fashioned flip clocks – and varying the temperature allows the pixels to communicate via infrared energy.

The study findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Tawfick’s interest in the interaction of elastic and capillary forces – or elasto-capillarity – started as a graduate student, spanned the basic science of hair wetting and led to his research in soft robotic displays at Illinois.

“An everyday example of elasto-capillarity is what happens to our hair when we get in the shower,” Tawfick said. “When our hair gets wet, it sticks together and bends or bundles as capillary forces are applied and released when it dries out.”

In the lab, the team created small boxes, or pixels, a few millimeters in size, that contain fins made of a flexible polymer that bend when the pixels are filled with fluid and drained using a system of tiny pumps. The pixels can have single or multiple fins and are arranged into arrays that form a display to convey information, Tawfick said.

Click here to see a video of a single-fin arrangement

Click here to see a video of a four-fin arrangement

“We are not limited to cubic pixel boxes, either,” Tawfick said. “The fins can be arranged in various orientations to create different images, even along curved surfaces. The control is precise enough to achieve complex motions, like simulating the opening of a flower bloom.”

The study reports that another feature of the new displays is the ability to send two simultaneous signals – one that can be seen with the human eye and another that can only be seen with an infrared camera.

“Because we can control the temperature of these individual droplets, we can display messages that can only be seen using an infrared device,” Tawfick said, “Or we can send two different messages at the same time.”

However, there are a few limitations to the new displays, Tawfick said.

While building the new devices, the team found that the tiny pumps needed to control the pixel fluids were not commercially available, and the entire device is sensitive to gravity – meaning that it only works while in a horizontal position.

“Once we turn the display by 90 degrees, the performance is greatly degraded, which is detrimental to applications like billboards and other signs intended for the public,” Tawfick said. “The good news is, we know that when liquid droplets become small enough, they become insensitive to gravity, like when you see a rain droplet sticking on your window and it doesn’t fall. We have found that if we use fluid droplets that are five times smaller, gravity will no longer be an issue.”

The team said that because the science behind gravity’s effect on droplets is well understood, it will provide the focal point for their next application of the emerging technology.

Tawfick said he is very excited to see where this technology is headed because it brings a fresh idea to a big market space of large reflective displays. “We have developed a whole new breed of displays that require minimal energy, are scaleable and even flexible enough to be placed onto curved surfaces.”

Illinois researchers Jonghyun Ha, Yun Seong Kim, Chengzhang Li, Jonghyun Hwang, Sze Chai Leung and Ryan Siu also participated in this research.

The Airforce Office of Scientific Research and the National Science Foundation supported this research.

Editor’s notes:

To reach Sameh Tawfick, call (217) 244-6303; email tawfick@illinois.edu.

The paper “Polymorphic display and texture integrated systems controlled by capillarity” is available online. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adh1321

END

Displays controlled by flexible fins and liquid droplets more versatile, efficient than LED screens

2023-06-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CU Anschutz researchers identify unique cell receptor, potential for new therapies

2023-06-30

AURORA, Colo. (June 30, 2023) – Researchers from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have identified a potential new immune checkpoint receptor that could lead to treatments for diseases such as lung and bowel cancer and autoimmune conditions including IBD.

The study, published today in Science Immunology, examines a family of 13 receptors, or proteins that transmit signals for cells to follow, called killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR). Of the 13 receptors, one is unique in that it has not readily been observed on immune cells of ...

A new bacterial blueprint to aid in the war on antibiotic resistance

2023-06-30

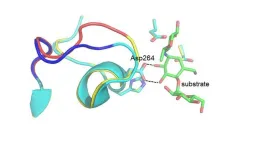

A team of scientists from around the globe, including those from Trinity College Dublin, has gained high-res structural insights into a key bacterial enzyme, which may help chemists design new drugs to inhibit it and thus suppress disease-causing bacteria. Their work is important as fears continue to grow around rising rates of antibiotic resistance.

The scientists, led by Martin Caffrey, Fellow Emeritus in Trinity’s School of Medicine and School of Biochemistry and Immunology, used next-gen X-ray crystallography and single particle cryo-electron microscopy ...

Climate disasters, traumatic events have long-term impacts on youths' academics

2023-06-30

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Experiencing traumatic events such as natural disasters may have long-term consequences for the academic progress and future food security of youth — a problem researchers said could worsen with the increased frequency of extreme weather events due to climate change.

In a study using data from Peru, researchers from Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences found that being exposed to a greater number of traumatic events or “shocks,” such as a natural disaster or loss of family income, in early ...

Researchers demonstrate single-molecule electronic "switch" using ladder-like molecules

2023-06-30

Researchers have demonstrated a new material for single-molecule electronic switches, which can effectively vary current at the nanoscale in response to external stimuli. The material for this molecular switch has a unique structure created by locking a linear molecular backbone into a ladder-type structure. A new study finds that the ladder-type molecular structure greatly enhances the stability of the material, making it highly promising for use in single-molecule electronics applications.

Reported in the journal Chem, the study shows that the ladder-type molecule serves as a robust and reversible molecular switch over a wide range of conductivity levels and different molecular ...

Can bone-strengthening exercises and/or drugs reduce fracture risk when older adults lose weight?

2023-06-30

A $7 million study beginning this summer at Wake Forest University and Wake Forest University School of Medicine will help determine whether a combination of resistance training plus bone-strengthening exercises and/or osteoporosis medication use can help older adults safely lose weight without sacrificing bone mass.

That paradox – that shedding pounds can help stave off heart disease and diabetes while increasing bone loss and subsequent fracture risk – has been a focus of Wake Forest researcher Kristen Beavers for about a decade.

Her previous research ...

Incidence of diabetes in children and adolescents during the pandemic

2023-06-30

About The Study: Incidence rates of type 1 diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis at diabetes onset in children and adolescents were higher after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic than before the pandemic. Increased resources and support may be needed for the growing number of children and adolescents with diabetes. Future studies are needed to assess whether this trend persists and may help elucidate possible underlying mechanisms to explain temporal changes.

Authors: Rayzel Shulman, M.D., ...

Association of preoperative high-intensity interval training with cardiorespiratory fitness, postoperative outcomes among adults undergoing major surgery

2023-06-30

About The Study: The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies including 832 patients suggest that preoperative high-intensity interval training may improve cardiorespiratory fitness and reduce postoperative complications. These findings support including high-intensity interval training in pre-habilitation programs before major surgery.

Authors: John C. Woodfield, Ph.D., of the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media ...

Scientists discover clues to aging and healing from a squishy sea creature

2023-06-30

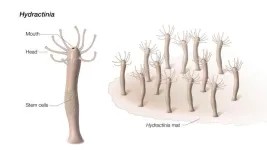

Insights into healing and aging were discovered by National Institutes of Health researchers and their collaborators, who studied how a tiny sea creature regenerates an entire new body from only its mouth. The researchers sequenced RNA from Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a small, tube-shaped animal that lives on the shells of hermit crabs. Just as the Hydractinia were beginning to regenerate new bodies, the researchers detected a molecular signature associated with the biological process of aging, also known as senescence. According to the study published in Cell Reports, Hydractinia demonstrates that the fundamental biological processes of healing and aging are intertwined, ...

Scientists designed new enzyme using Antarctic bacteria and computer calculations

2023-06-30

For the first time, researchers have succeeded in predicting how to change the optimum temperature of an enzyme using large computer calculations. A cold-adapted enzyme from an Antarctic bacterium was used as a basis. The study is to be published in the journal Science Advances and is a collaboration between researchers at Uppsala University and the University of Tromsø.

The type of cold-adapted enzymes used by the researchers for their study can be found in bacteria and fish that live in icy water, for example. Evolution has shaped ...

Protection of biodiversity and ecosystems: we are still far from the European targets

2023-06-30

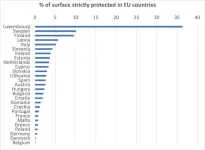

The goal of fully protecting 10% of the EU's land area is ambitious for European countries that have been profoundly shaped by millennia of human transformation. A recently published study, coordinated by the University of Bologna, has carried out the first analysis at European level on the strictly protected areas (classified by the IUCN as integral reserves, wilderness areas and national parks) across the EU, studying how extensive integral protection is across biogeographical regions, countries and elevation gradients.

"We have discovered – explains Prof. Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, conservation ...