(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON – Georgetown University Medical Center neuroscientists say the brain’s auditory lexicon, a catalog of verbal language, is actually located in the front of the primary auditory cortex, not in back of it -- a finding that upends a century-long understanding of this area of the brain. The new understanding matters because it may impact recovery and rehabilitation following a brain injury such as a stroke.

The findings appear in Neurobiology of Language on July 5, 2023.

Riesenhuber’s lab showed the existence of a lexicon for written words at the base of the brain’s left hemisphere in a region known as the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA) and subsequently determined that newly learned written words are added to the VWFA. The present study sought to test whether a similar lexicon existed for spoken words in the so-called Auditory Word Form Area (AWFA), located anterior to primary auditory cortex.

“Since the early 1900s, scientists believed spoken word recognition took place behind the primary auditory cortex, but that model did not fit well with many observations from patients with speech recognition deficits, such as stroke patients,” says Maximilian Riesenhuber, PhD, professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Georgetown University Medical Center and senior author of this study. “Our discovery of an auditory lexicon more towards the front of the brain provides a new target area to help us understand speech comprehension deficits.”

In the study, led by Srikanth Damera, MD, PhD, 26 volunteers went through three rounds of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans to examine their spoken word processing abilities. The technique used in this study was called functional-MRI rapid adaptation (fMRI-RA), which is more sensitive than conventional fMRI in assessing representation of auditory words as well as the learning of new words.

“In future studies, it will be interesting to investigate how interventions directed at the AWFA affect speech comprehension deficits in populations with different types of strokes or brain injury,” says Riesenhuber. “We are also trying to understand how the written and spoken word systems interact. Beyond that, we are using the same techniques to look for auditory lexica in other parts of the brain, such as those responsible for speech production.”

Josef Rauschecker, PhD, DSc, professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Georgetown and co-author of the study, adds that many aspects of how the brain processes words, either written or verbal, remain unexplored.

“We know that when we learn to speak, we rely on our auditory system to tell us whether the sound we’ve produced accurately represents our intended word,” he said. “We use that feedback to refine future attempts to say the word. However, the brain’s process for this remains poorly understood – both for young children learning to speak for the first time, but also for older people learning a second language.”

###

In addition to Riesenhuber , Damera and Rauschecker, the other authors at Georgetown University are Lillian Chang, Plamen Nikolov, James Mattei, Suneel Banerjee, Patrick H. Cox and Xiong Jiang. Laurie S. Glezer is at San Diego State University, CA. This work was supported by funds from the National Science Foundation grant BCS-1756313. Additional support was provided by NIH grant 1S10OD023561. This work also used resources provided through the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant ACI-1548562.

The authors declare no personal financial interests related to the study.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

As a top academic health and science center, Georgetown University Medical Center provides, in a synergistic fashion, excellence in education — training physicians, nurses, health administrators and other health professionals, as well as biomedical scientists — and cutting-edge interdisciplinary research collaboration, enhancing our basic science and translational biomedical research capacity in order to improve human health. Patient care, clinical research and education is conducted with our academic health system partner, MedStar Health. GUMC’s mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on social justice and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or “care of the whole person.” GUMC comprises the School of Medicine, the School of Nursing, School of Health, Biomedical Graduate Education, and Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. Designated by the Carnegie Foundation as a doctoral university with "very high research activity,” Georgetown is home to a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health, and a Comprehensive Cancer Center designation from the National Cancer Institute. Connect with GUMC on Facebook (Facebook.com/GUMCUpdate) and on Twitter (@gumedcenter).

END

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Elephants eat plants. That’s common knowledge to biologists and animal-loving schoolchildren alike. Yet figuring out exactly what kind of plants the iconic herbivores eat is more complicated.

A new study from a global team that included Brown conservation biologists used innovative methods to efficiently and precisely analyze the dietary habits of two groups of elephants in Kenya, down to the specific types of plants eaten by which animals in the group. Their findings on the habits of ...

Endometriosis is linked to a reduction in fertility in the years preceding a definitive surgical diagnosis of the condition, according to new research published today (Wednesday) in Human Reproduction [1], one of the world’s leading reproductive medicine journals.

In the first study to look at birth rates in a large group of women who eventually received a surgical verification of endometriosis, researchers in Finland found that the number of first live births in the period before diagnosis was half that of women without the painful condition. ...

Biomechanical studies on the arachnid-like front “legs” of an extinct apex predator show that the 2-foot (60-centimeter) marine animal Anomalocaris canadensis was likely much weaker than once assumed. One of the largest animals to live during the Cambrian, it was probably agile and fast, darting after soft prey in the open water rather than pursuing hard-shelled creatures on the ocean floor. The study is published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

First discovered in the late 1800s, Anomalocaris canadensis—which means “weird shrimp from Canada” in Latin—has long been thought to be responsible ...

Changes in water conditions interact to affect how Trinidadian guppies protect themselves from predators, scientists at the University of Bristol have discovered.

Known stressors, such as increased temperature and reduced visibility, when combined, cause this fish to avoid a predator less, and importantly, form looser protective shoals.

The findings, published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, show guppies’ responses are more affected by the interaction of these stressors than if they acted independently.

Natural ...

New research reveals that wild birds living in vineyards can be highly susceptible to contamination by triazole fungicides, more so than in other agricultural landscapes. Exposure to these fungicides at a field-realistic level were found to disrupt hormones and metabolism, which can impact bird reproduction and survival.

“We found that birds can be highly contaminated by triazoles in vineyards,” says Dr Frédéric Angelier, Senior Researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research, France. “This contamination was much higher in vineyards relative to other crops, emphasizing that contaminants may especially put birds at risk in these ...

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 16:00 LONDON TIME (BST) / 11:00 (US ET) ON TUESDAY 4TH JULY 2023

Analysis of global tracking data for 77 species of petrel has revealed that a quarter of all plastics potentially encountered in their search for food are in remote international waters – requiring international collaboration to address.

The extensive study assessed the movements of 7,137 individual birds from 77 species of petrel, a group of wide-ranging migratory seabirds including the Northern Fulmar and European Storm-petrel, and the Critically Endangered Newell’s Shearwater.

This is ...

New study reveals the areas most at risk of plastic exposure by the already endangered seabirds.

The study, now published in Nature Communications, brings together more than 200 researchers worldwide around a pressing challenge, widely recognized as a growing threat to marine life: the pollution of oceans by plastic. Coordinated by Dr. Maria Dias, researcher at the Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (cE3c) at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon (Ciências ULisboa), ...

New research suggests that the use of an omega-3 rich oil called “ahiflower oil” can prevent damage to honey bee mitochondria caused by neonicotinoid pesticides. This research is part of an ongoing project by PhD student Hichem Menail of the Université de Moncton in New Brunswick, Canada.

“Pesticides are a major threat to insect populations and as insects are at the core of ecosystem richness and balance, any loss in insect biodiversity can lead to catastrophic outcome,” says Mr Menail, adding that pesticide-related pollinator declines are also a huge concern for food crops globally.

Imidacloprid, ...

Global efforts to reduce infectious disease rates must have a greater focus on older children and adolescents after a shift in disease burden onto this demographic, according to a new study.

The research, led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, has found that infectious disease control has largely focused on children aged under five, with scarce attention on young people between five and 24 years old.

Published in The Lancet, the study found three million children and adolescents die from infectious diseases every year, equivalent to one death every 10 seconds. It looked at data across 204 countries ...

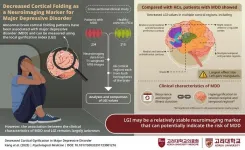

In appearance, the human brain’s outermost layer, called the cortex, is a maze of tissue folds. The peaks or raised surfaces of these folds, called gyri, play an important role in the proper functioning of the brain. Improper gyrification—or the development of gyri—has been implicated in various neurological disorders, one of them being the debilitating and widespread mental illness, major depressive disorder (MDD). Although prior studies have shown that abnormal cortical folding patterns are associated with MDD, ...