(Press-News.org) The same AI technology used to mimic human art can now synthesize artificial scientific data, advancing efforts toward fully automated data analysis.

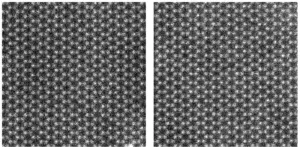

Researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have developed an AI that generates artificial data from microscopy experiments commonly used to characterize atomic-level material structures. Drawing from the technology underlying art generators, the AI allows the researchers to incorporate background noise and experimental imperfections into the generated data, allowing material features to be detected much faster and more efficiently than before.

“Generative AIs take information and generate new things that haven’t existed before in the world, and now we’ve leveraged that for the goal of automated data analysis,” said Pinshane Huang, a U. of I. professor of materials science and engineering and a project co-lead. “What is used to make paintings of llamas in the style of Monet on the internet can now make scientific data so good it fools me and my colleagues.”

Other forms of AI and machine learning are routinely used in materials science to assist with data analysis, but they require frequent, time-consuming human intervention. Making these analysis routines more efficient requires a large set of labeled data to show the program what to look for. Moreover, the data set needs to account for a wide range of background noise and experimental imperfections to be effective, effects that are difficult to model.

Since collecting and labeling such a vast data set using a real microscope is infeasible, Huang worked with U. of I. physics professor Bryan Clark to develop a generative AI that could create a large set of artificial training data from a comparatively small set of real, labeled data. To achieve this, the researchers used a cycle generative adversarial network, or CycleGAN.

“You can think of a CycleGAN as a competition between two entities,” Clark said. “There’s a ‘generator’ whose job is to imitate a provided data set, and there’s a ‘discriminator’ whose job is to spot the differences between the generator and the real data. They take turns trying to foil each other, improving themselves based on what the other was able to do. Ultimately, the generator can produce artificial data that is virtually indistinguishable from the real data.”

By providing the CycleGAN with a small sample of real microscopy images, the AI learned to generate images that were used to train the analysis routine. It is now capable of recognizing a wide range of structural features despite the background noise and systematic imperfections.

“The remarkable part of this is that we never had to tell the AI what things like background noise and imperfections like aberration in the microscope are,” Clark said. “That means even if there’s something that we hadn’t thought about, the CycleGAN can learn it and run with it.”

Huang’s research group has incorporated the CycleGAN into their experiments to detect defects in two-dimensional semiconductors, a class of materials that is promising for applications in

electronics and optics but is difficult to characterize without the aid of AI. However, she observed that the method has a much broader reach.

“The dream is to one day have a ‘self-driving’ microscope, and the biggest barrier was understanding how to process the data,” she said. “Our work fills in this gap. We show how you can teach a microscope how to find interesting things without having to know what you’re looking for.”

***

The study, “Leveraging generative adversarial networks to create realistic scanning transmission electron microscopy images,” was published in the journal NPJ Computational Materials.

Huang is a Racheff Faculty Scholar and an affiliate of the Materials Research Laboratory at the U. of I. Clark is an affiliate of the Center for Artificial Intelligence Innovation at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications and the Illinois Quantum Information Science and Technology Center at the U. of I.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy.

END

Generative AI ‘fools’ scientists with artificial data, bringing automated data analysis closer

2023-07-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Satisfaction with online dating app depends on what you’re looking for

2023-07-11

With an estimated 75 million active users each month, Tinder is the most popular dating app in the world. But a new study by Stanford Medicine researchers and collaborators has found, surprisingly - though perhaps not to users of the app - that many users are not swiping for dates.

In a survey of more than a thousand Tinder users, half said they were not interested in meeting offline, and nearly two-thirds were already married or "in a relationship."

In fact, the psychological motivations behind people's use of the app varied widely and had a strong influence on their satisfaction with the app and the dates it led to, according to the study published June 23 ...

University of Illinois study finds turning food waste into bioenergy can become a profitable industry

2023-07-11

URBANA, Ill. — Food waste is a major problem around the world. In the United States, an estimated 30 to 40% of edible food is lost or wasted, costing billions of dollars each year. One potential solution is to divert food waste from landfills to renewable energy production, but this isn’t done on a large scale anywhere. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign investigates the feasibility of implementing energy production from food waste in the state of Illinois.

“We have a large amount of organic waste in the U.S., which eventually enters landfills and emits greenhouse gasses. However, this material ...

Hepatic hydrogen sulfide levels are reduced in mouse model of progeria

2023-07-11

“To date, no studies have directly measured [hydrogen sulfide] production in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- July 11, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 12, entitled, “Hepatic hydrogen sulfide levels are reduced in mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.”

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a rare ...

Missing a rare cause of hereditary cancer

2023-07-11

New research from Cedars-Sinai Cancer investigators could warrant reconsideration of current screening guidelines to include a poorly recognized cause of Lynch syndrome, the most common cause of hereditary colorectal and endometrial cancers. Their study, published today in the JNCCN—Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, concluded that the guidelines leave a significant number of patients undiagnosed.

“When patients with Lynch syndrome—whose first cancers generally appear at an early age—aren’t diagnosed promptly, they don’t get appropriate follow-up or surveillance,” said Megan Hitchins, ...

U of M Medical School receives DARPA award to develop detection tools for early symptoms of depression, psychosis and suicidality

2023-07-11

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (07/11/2023) — Researchers at the University of Minnesota Medical School recently received a four-year award from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA’s) Neural Evidence Aggregation Tool program. The goal of their project— titled Fast, Reliable Electrical Unconscious Detection (FREUD)—is to develop tools to better detect early symptoms of depression, psychosis and suicidality, with the intent that treatment can be started as early in a condition’s trajectory as possible.

“It’s exactly those early moments when getting someone therapy or mental health services could save their life or ...

Research aims to identify better COPD diagnosis in African American patients

2023-07-11

DENVER — Recently published research suggests that despite showing clear symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), many African Americans are not officially diagnosed with the disease due to flaws in diagnosis methods. The Research was led by National Jewish Health and recently published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine from the COPDGene study.

Fixed-ratio spirometry, a standard method of measuring respiratory capacity, has long been used as a method of detecting COPD. ...

With a comfort promise, new clinic aims to eliminate pain in kids

2023-07-11

Each year, too many kids in the East Bay suffer needlessly from pain related to long-term serious illness, including migraines, joint and abdominal pain, sickle cell anemia and more. A new UCSF Health pain clinic in Walnut Creek is opening to provide relief.

The new clinic extends the reach of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland. The Center is one of the nation’s most innovative and comprehensive integrative ...

Potential targets to delay motor aging revealed by C. elegans genome-wide screen

2023-07-11

Genome-wide screen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans reveals potential targets to delay motor aging, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase VPS-34; genetic and pharmacological partial inhibition of VPS-34 improves neurotransmission and muscle integrity through increased PI(3)P-PI-PI(4)P conversion, ameliorating motor aging in both worms and mice.

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002165

Article ...

Scientists build a healthy dietary pattern using ultra-processed foods

2023-07-11

GRAND FORKS, N.D., July 11, 2023 ̶ Scientists at the USDA Agricultural Research Service’s (ARS) Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research Center led a study that demonstrates it is possible to build a healthy diet with 91 percent of the calories coming from ultra-processed foods (as classified using the NOVA scale) while still following the recommendations from the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The study highlights the versatility of using DGA recommendations in constructing healthy menus.

“The study is a proof-of-concept that shows a more balanced view of healthy ...

Low-glucose sensor in the brain promotes blood glucose balance

2023-07-11

The body’s blood glucose level needs to be maintained in a relatively narrow range. It cannot be too high, as it can lead to diabetes, and it cannot be too low because it can cause fainting or even death.

“There are many glucose-sensing neurons in the brain that are thought to actively participate in detecting small changes of glucose levels in the body and then trigger responses accordingly to return the level to a healthy range,” said Dr. Yong Xu, professor of pediatrics – nutrition, ...