(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – For the first time, researchers have developed a model to estimate how much energy the original colonizers of New Zealand expended to maintain their body temperatures on the cold, harrowing ocean journey from Southeast Asia.

Results showed that people making the first voyages from Tahiti to New Zealand in sailing canoes would expend 3.3 to 4.8 times more energy on thermoregulation – the technical term for maintaining body temperature - than those making a trip of similar length to Hawaii.

The ocean route to New Zealand required much more energy for thermoregulation because it went through harsher and colder conditions than the one to Hawaii, said Alvaro Montenegro, lead author of the study and associate professor of geography at The Ohio State University.

The findings help provide additional evidence supporting the long-standing theory of why Polynesians of today have a distinctive body type – relatively larger, heavier, bulkier – that is more often found in populations that live in higher latitudes with colder climates.

“It has been long hypothesized that the first trips to New Zealand were much harder on the body of settlers than trips of similar lengths to places like Hawaii,” Montenegro said.

“We were able to put together a model to actually measure how much more energy for thermoregulation it would take for people to get there – and show why larger, heavier people would have been more likely to survive the trip. That’s one reason why their descendants today may have the body types they do.”

The study was published today (July 12, 2023) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Although much of East Polynesia is tropical, the southern third, including New Zealand, ranges from a warm- to cool-temperate climate. Researchers say that may be one of the reasons it was one of the last places on Earth to become inhabited. The first people arrived in New Zealand about the 14th century.

“The basic question is how difficult would it be on human physiology to sail out of the tropics on these long-distance colonizing voyages through much harsher environmental conditions than they were used to?” Montenegro said.

Researchers believe that these original settlers used double-hulled sailing canoes that probably each had at most a few dozen voyagers on board.

Montenegro and colleagues had previously developed a voyage simulation model that estimates how far these boats would travel each day based on winds and currents. In this study, the researchers used that model combined with likely environmental conditions that voyagers would encounter, including air temperatures and wind.

To evaluate how body size would affect energy use for thermoregulation on these voyages, the researchers used female and male bodies of three different types. One body type resembled Polynesians of today, a second one was of a higher weight, and the third type had higher body weight and additional subcutaneous fat layer thickness.

The researchers estimated how much energy it would take travelers to maintain their body temperature sailing from Tahiti to New Zealand and compared that to travelers going to Hawaii, which they estimated would take about 23 days, similar to the 25-day trip to New Zealand.

The model the researchers used did not account for energy used by physical activity, which of course would be an additional need for the voyagers.

Results showed that the trip to New Zealand would take significantly more energy than the trip to Hawaii, Montenegro said.

Based on a summer trip (which would require less energy than a winter trip), each traveler to New Zealand would require an average of an extra 965 calories a day compared to those going to Hawaii to maintain their body temperature.

If this deficit was completely made up by burning fat, those going to New Zealand would lose an average of an extra 5.9 pounds at the end of a 25-day trip. If the difference was compensated just by use of muscle mass, the whole trip extra weight loss would be about 13.3 pounds.

Model calculations showed that travelers with a larger body size experienced lower heat loss, and so had an energy advantage compared to those of smaller body sizes. The advantage was greater for females.

“The trip would be difficult under any circumstances, but our results showed that people of larger body size would have had an advantage under the harsh conditions they faced,” Montenegro said.

These findings line up with the larger bodies of Polynesian populations today, including the fact that females are about 31% heavier, and males 24% heavier, than populations to their west.

“Our analysis can’t definitively prove that the size differences we see in Polynesia today are the result of larger people being more likely to survive the original trips and colonizing the region, but it certainly is consistent with that fact,” he said.

Other authors on the study were Alexandra Niclou of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and University of Notre Dame; Atholl Anderson of Australian National University and University of Canterbury; Scott Fitzpatrick of the University of Oregon; and Cara Ocobock of the University of Notre Dame.

END

How larger body sizes helped the colonizers of New Zealand

More weight helped voyagers survive cold ocean journey

2023-07-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Could AI-powered robot “companions” combat human loneliness?

2023-07-12

AUKLAND, NZ and DURHAM, N.C. – Companion robots enhanced with artificial intelligence may one day help alleviate the loneliness epidemic, suggests a new report from researchers at Auckland, Duke, and Cornell Universities.

Their report, appearing in the July 12 issue of Science Robotics, maps some of the ethical considerations for governments, policy makers, technologists, and clinicians, and urges stakeholders to come together to rapidly develop guidelines for trust, agency, engagement, and real-world efficacy.

It also proposes a new way to measure whether a companion robot is helping someone.

“Right now, all the evidence ...

Those who are smarter live longer

2023-07-12

Cognitive abilities not only vary among different species but also among individuals within the same species. It is expected that smarter individuals live longer, as they are likely to make better decisions, regarding habitat and food selection, predator avoidance, and infant care. To investigate the factors influencing life expectancy of wild gray mouse lemurs, researchers from the German Primate Center conducted a long-term study in Madagascar. They administered four different cognitive tests and two personality tests to 198 animals, while also measuring their weight and tracking their survival over several years. ...

Secrets of Egyptian painters revealed by chemistry

2023-07-12

Within the scope of a vast research program undertaken in coordination with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and the University of Liège, an international team—including scientists from the CNRS, Sorbonne University, and Université Grenoble Alpes—has revealed the artistic license exercised in two ancient Egyptian funerary paintings (dating to ~1,400 and ~1,200 BCE, respectively), as evident in newly discovered details invisible to the naked eye. Their findings are published in PLOS ONE (12 July).

The language of ancient ...

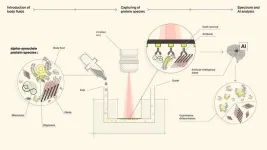

A novel biosensor for detecting neurogenerative disease proteins

2023-07-12

By combining multiple advanced technologies into a single system, EPFL researchers have made a significant step forward in diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD). This novel device is known as the ImmunoSEIRA sensor, a biosensing technology that enables the detection and identification of misfolded protein biomarkers associated with NDDs. The research, published today in Science Advances, also harnesses the power of artificial intelligence (AI) by employing neural networks to quantify disease ...

Eliminating public health scourge can also benefit agriculture

2023-07-12

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease that causes organ damage and death, affected more than 250 million people worldwide in 2021, according to the World Health Organization.

One of the world’s most burdensome neglected tropical diseases, schistosomiasis occurs when worms are transmitted from freshwater snails to humans. The snails thrive in water with plants and algae that proliferate in areas of agricultural runoff containing fertilizer. People become infected during routine activities in infested water.

Researchers from the University of Notre Dame, in a study recently published in Nature, found that removing invasive vegetation at water access points in and around several ...

Rosé renaissance: Spanish study uncorks ultrasound for superior wine quality

2023-07-12

Since the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) approved the use of ultrasound to promote the extraction of grape compounds back in 2019, its application for obtaining superior red wines has been studied extensively.

Now researchers are turning their attention to rosé – an expanding market which has seen strong growth over the past 15 years. A team from the University of Castilla-La Mancha and the University of Murcia in Spain used high-power ultrasound technology to treat Monastrell crushed grapes – a process known as sonication ...

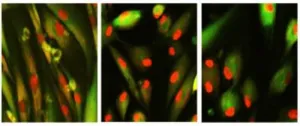

NEW STUDY: Discovery of chemical means to reverse aging and restore cellular function

2023-07-12

On July 12, 2023, a new research paper was published in Aging, titled, “Chemically induced reprogramming to reverse cellular aging.”

BUFFALO, NY- July 12, 2023 – In a groundbreaking study, researchers have unlocked a new frontier in the fight against aging and age-related diseases. The study, conducted by a team of scientists at Harvard Medical School, has published the first chemical approach to reprogram cells to a younger state. Previously, this was only achievable using a powerful gene ...

Empowering student ideas: NPS introduces the Naval Innovation Exchange

2023-07-12

The Naval Innovation Center (NIC) at the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) in Monterey, Calif., is part of the Secretary of the Navy’s initiative to leverage the power of American innovation for national security. Integral to the function of the NIC is the Naval Innovation Exchange (NIX), a new program that organizes and empowers multidisciplinary teams of NPS students and faculty focused on developing prototype research solutions.

While in its early stages, the NIC at NPS will leverage and empower ...

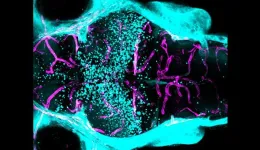

Researchers uncover signal needed for blood-brain barrier

2023-07-12

At a glance:

Working with mice and zebrafish, researchers identify a gene, expressed in neurons, that produces a signal needed for development and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier.

When mutated, the gene makes certain regions of the blood-brain barrier more permeable.

The findings could help scientists control the blood-brain barrier — important for delivering drugs into the central nervous system or countering damage from neurodegenerative disease

What makes the vital layer of protective cells around the brain and spinal cord — ...

Psychedelic-assisted therapies for patients with PTSD

2023-07-12

Psychedelic-based therapies are poised to change the treatments that psychiatrists can offer patients.

“I often talk about psychedelic treatments as catalysts for change, for both the individual and the field of psychiatry,” said Medical University of South Carolina psychiatrist Jennifer Jones, M.D., who conducts research on these treatments.

The highly anticipated approval of MDMA, or “ecstasy,” to treat post-traumatic stress disorder would be the first for a psychedelic drug, ushering in changes for patients, mental health providers and society. The Food and Drug Administration is expected to issue a decision on MDMA-assisted ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Current Pharmaceutical Analysis releases Volume 22, Issue 2 with open access research

Researchers capture thermal fluctuations in polymer segments for the first time

16-year study finds major health burden in single‑ventricle heart

Disposable vapes ban could lead young adults to switch to cigarettes, study finds

Adults with concurrent hearing and vision loss report barriers and challenges in navigating complex, everyday environments

Breast cancer stage at diagnosis differs sharply across rural US regions

Concrete sensor manufacturer Wavelogix receives $500,000 grant from National Science Foundation

California communities’ recovery time between wildfire smoke events is shrinking

Augmented reality job coaching boosts performance by 79% for people with disabilities

Medical debt associated with deferring dental, medical, and mental health care

AAI appoints Anand Balasubramani as Chief Scientific Programs Officer

Prior authorization may hinder access to lifesaving heart failure medications

Scholars propose transparency, credit and accountability as key principles in scientific authorship guidelines

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop DDINet for accurate and scalable drug-drug interaction prediction

IEEE researchers achieve 20x signal boost in cerebral blood flow monitoring with next-generation interferometric diffusing wave spectroscopy

IEEE researchers achieve low-power ultrashort mid-IR pulse compression

Deep-sea natural compound targets cancer cells through a dual mechanism

Antibiotics can affect the gut microbiome for several years

Study: Electrical stimulation can restore ability to move limbs, receive sensory feedback after spinal cord injury

Rice scientists unveil new tool to watch quantum behavior in action

Gene-based therapies poised for major upgrade thanks to Oregon State University research

Extreme heat has extreme effects r—but some like it hot

Blood marker for Alzheimer’s may also be useful in heart and kidney diseases

Climate extremes hinder early development in young birds

Climate policies: The swing voters that determine their fate

Building protection against infectious diseases with nanostructured vaccines

Oval orbit casts new light on black hole - neutron star mergers

Does online sports gambling affect substance use behaviors?

How do rapid socio-environmental transitions reshape cancer risk?

Do abortion bans affect birth rates and food-assistance costs?

[Press-News.org] How larger body sizes helped the colonizers of New ZealandMore weight helped voyagers survive cold ocean journey