(Press-News.org) Averting our eyes from things that scare us may be due to a specific cluster of neurons in a visual region of the brain, according to new research at the University of Tokyo. Researchers found that in fruit fly brains, these neurons release a chemical called tachykinin which appears to control the fly’s movement to avoid facing a potential threat. Fruit fly brains can offer a useful analogy for larger mammals, so this research may help us better understand our own human reactions to scary situations and phobias. Next, the team want to find out how these neurons fit into the wider circuitry of the brain so they can ultimately map out how fear controls vision.

Do you cover your eyes during horror movies? Or perhaps the sight of a spider makes you turn and run? Avoiding looking at things which scare us is a common experience, for humans and animals. But what actually makes us avert our gaze from the things we fear? Researchers have found that it may be due to a group of neurons in the brain which regulates vision when feeling afraid.

“We discovered a neuronal mechanism by which fear regulates visual aversion in the brains of Drosophila (fruit flies). It appears that a single cluster of 20-30 neurons regulates vision when in a state of fear. Since fear affects vision across animal species, including humans, the mechanism we found may be active in humans as well,” explained Assistant Professor Masato Tsuji from the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Tokyo.

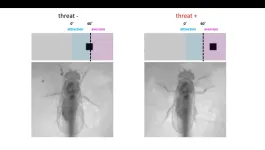

The team used puffs of air to simulate a physical threat and found that the flies’ walking speed increased after being puffed at. The flies also would choose a puff-free route if offered, showing that they perceived the puffs as a threat (or at least preferred to avoid them). Next the researchers placed a small black object, roughly the size of a spider, 60 degrees to the right or left of the fly. On its own the object didn’t cause a change in behavior, but when placed following puffs of air, the flies avoided looking at the object and moved so that it was positioned behind them.

To understand the molecular mechanism underlying this aversion behavior, the team then used mutated flies in which they altered the activity of certain neurons. While the mutated flies kept their visual and motor functions, and would still avoid the air puffs, they did not respond in the same fearful manner to visually avoid the object.

“This suggested that the cluster of neurons which releases the chemical tachykinin was necessary for activating visual aversion,” said Tsuji. “When monitoring the flies’ neuronal activity, we were surprised to find that it occurred through an oscillatory pattern, i.e., the activity went up and down similar to a wave. Neurons typically function by just increasing their activity levels, and reports of oscillating activity are particularly rare in fruit flies because up until recently the technology to detect this at such a small and fast scale didn’t exist.”

By giving the flies genetically encoded calcium indicators, the researchers could make the flies' neurons shine brightly when activated. Thanks to the latest imaging techniques, they then saw the changing, wavelike pattern of light being emitted, which was previously averaged out and missed.

Next, the team wants to figure out how these neurons fit into the broader circuitry of the brain. Although the neurons exist in a known visual region of the brain, the researchers do not yet know from where the neurons are receiving inputs and to where they are transmitting them, to regulate visual escape from objects perceived as dangerous.

“Our next goal is to uncover how visual information is transmitted within the brain, so that we can ultimately draw a complete circuit diagram of how fear regulates vision,” said Tsuji. “One day, our discovery might perhaps provide a clue to help with the treatment of psychiatric disorders stemming from exaggerated fear, such as anxiety disorders and phobias.”

#####

Paper Title:

Masato Tsuji, Yuto Nishizuka, Kazuo Emoto. Threat gates visual aversion via theta activity in Tachykinergic neurons. Nature Communications. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39667-z

Funding

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the Graduate Program for Leaders in Life Innovation (GPLLI), MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Dynamic regulation of brain function by Scrap and Build system” (KAKENHI 16H06456), JSPS (KAKENHI 16H02504), WPI-IRCN, AMED-CREST (JP21gm1310010), JST-CREST (JPMJCR22P6), Toray Foundation, Naito Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, and Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Useful Links

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

International Research Center for Neurointelligence: https://ircn.jp/en/

Research Contacts:

Assistant Professor Masato Tsuji

Department of Biological Sciences

Graduate School of Science

The University of Tokyo

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan

Email: mtsuji@bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Tel.:+81-3-5841-4427

Professor Kazuo Emoto

Department of Biological Sciences

Graduate School of Science

The University of Tokyo

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan

Email: emoto@bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Tel.: +81-3-5841-4426

Press contact:

Mrs. Nicola Burghall

Public Relations Group, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan

press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

END

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) – Rising ocean temperatures are sweeping the seas, breaking records and creating problematic conditions for marine life. Unlike heatwaves on land, periods of abrupt ocean warming can surge for months or years. Around the world these ‘marine heatwaves’ have led to mass species mortality and displacement events, economic declines and habitat loss. New research reveals that even areas of the ocean protected from fishing are still vulnerable to these extreme events fueled by climate change.

A study published today in Global Change Biology, led by researchers at UC Santa ...

A collaboration of scientists from The University of Manchester and the University of Hong Kong have found a source for the mysterious alignment of stars near the Galactic Centre.

The alignment of planetary nebulae was discovered ten years ago by a Manchester PhD student, Bryan Rees, but has remained unexplained.

New data obtained with the European Southern Observatory Very Large Telescope in Chile and the Hubble Space Telescope, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, has confirmed the alignment but also found a particular ...

· Colorism – system of inequality that views lighter skin as more beautiful and advantageous – motivates skin lightening

· Users aren’t aware of adulterated ingredients in over-the-counter products such as mercury and steroids

· Products are purchased from chain grocery stores or online, used without medical advice

CHICAGO --- Skin lightening is prevalent in the U.S. among skin of color individuals – particularly women – but the people who use those products don’t know the risks, reports a new Northwestern ...

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

EMBARGOED UNTIL 05:01 LONDON TIME (GMT) ON THURSDAY 13 JULY 2023

Images and paper available at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/18XRYP9dHcC1Z8lc3B86j3k6BzgIesqUS?usp=sharing

Small-winged and lighter coloured butterflies likely to be at greatest threat from climate change

The family, wing length and wing colour of tropical butterflies all influence their ability to withstand rising temperatures, say a team led by ecologists at the University of Cambridge. The researchers believe this could help identify species whose survival is under threat from climate change.

Butterflies with smaller or lighter coloured wings are likely to ...

Defying conventional wisdom, researchers have uncovered a novel coupling mechanism involving leaky mode, previously has been considered unsuitable for high-density integration in photonic circuits. This unexpected finding opens new possibilities for dense photonic integration, revolutionizing the scalability and application of photonic chips in optical computing, quantum communication, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), optical metrology, and biochemical sensing.

In a recent Light Science & Application publication, Sangsik Kim, associate professor of electrical engineering ...

A study examining unemployment and underemployment figures and suicide rates in Australia has found both were significant drivers of suicide mortality between 2004-2016.

The researchers say the findings indicate that economic policies such as a Job Guarantee, which prioritise full employment, should be a core part of any comprehensive national suicide prevention strategy.

Predictive modelling also revealed an estimated 9.5 percent of suicides reported during that time resulted directly from unemployment ...

Overview

Associate Professor Hiroto Sekiguchi (Department of Electrical and Electronic Information Engineering, Toyohashi University of Technology) and Assistant Professor Susumu Setogawa and Associate Professor Noriaki Ohkawa (Comprehensive Research Facilities for Advanced Medical Science, Dokkyo Medical University; Assistant Professor Setogawa is currently a Specially Appointed Assistant Professor at University Public Corporation Osaka) have developed a flexible electrocorticography (Note 1) film for simultaneous detection of multisensory information (Note 2) from multiple regions of the cerebral cortex by placing neural ...

Mycelium, an incredible network of fungal strands that can thrive on organic waste and in darkness, could be a basis for sustainable fireproofing. RMIT researchers are chemically manipulating its composition to harness its fire-retardant properties.

Associate Professor Tien Huynh, an expert in biotechnology and mycology, said they’ve shown that mycelium can be grown from renewable organic waste.

“Fungi are usually found in a composite form mixed with residual feed material, but we found a way to grow pure mycelium sheets that can be layered and engineered into different uses – from flat panels for the building industry to a leather-like material for ...

The structure of a molecular junction with noncovalent interaction plays a key role in electron transport, reveals a recent study conducted by researchers at Tokyo Tech. Through simultaneous surface-enhanced Raman scattering and current–voltage measurements, they found that a single dimer junction of naphthalenethiol molecule shows three different bondings, namely π–π intermolecular and through-π and through-space molecule–electrode interactions.

The π–π interaction is a type of noncovalent interaction that occurs when the electron clouds in the π orbitals ...

New research suggests that targeting autoimmune inflammation associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) using two drugs, one of them already approved for multiple sclerosis, could be a promising approach for treatment.

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. It leads to the gradual loss of muscle control, eventually resulting in paralysis and difficulty with speech, swallowing, and breathing. The exact cause of ALS is not fully understood, and currently, there is no cure ...