(Press-News.org) It’s been 22 years since UC Davis MIND Institute Medical Director Randi Hagerman and her husband, researcher Paul Hagerman, discovered the neurodegenerative condition called FXTAS (fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome). Hagerman, a pediatrician known for her enthusiasm for her work and patients, has been studying FXTAS ever since, seeking to develop treatments for it.

She was recently awarded her 24th consecutive year of funding from the National Institutes of Health for her fragile X-related work, a five-year, $3.2 million grant. The study has evolved over the years and is now focused on better understanding the characteristics, or phenotype, of FXTAS.

FXTAS causes tremors, balance problems, dementia and other neurological challenges. It gets worse over time and there are no approved treatments — only therapies to manage symptoms.

The syndrome is caused by a “premutation” expansion of the FMR1 gene. It’s genetically related to fragile X syndrome. Both are caused by different-sized changes in the FMR1 gene. Fragile X syndrome starts in early development, and includes intellectual disability, developmental challenges and often, autism. FXTAS begins in late adulthood. The premutation usually runs in families.

Hagerman is an endowed chair in fragile X research. In this Q&A, she shares details about her research, what she’s focused on next and why she’s hopeful about future treatments.

What is the goal of the FXTAS study?

We’re trying to better understand FXTAS, which leads to tremor and balance problems as individuals age, particularly in their 60s. We’re studying the progression of FXTAS, which is often misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s and even Alzheimer’s, as it can also be associated with cognitive decline.

About 1 in 200 females and 1 in 400 males have the premutation in the general population. We’re trying to understand the different phenotypes, or presentations, between males and females. Males tend to develop FXTAS symptoms earlier and about half develop dementia. Females have a milder form, with less white matter disease in the brain according to our MRI studies. But females may also have autoimmune problems and more significant anxiety and depression.

Who is in the study?

We’ll have a total of about 160 people after enrolling additional participants from more diverse backgrounds this year. Some participants have been part of the study for 10-15 years. That includes men and women who either have a FXTAS diagnosis or who have early signs of the condition but don’t yet have FXTAS, ages 40 to 85. This includes mild tremor, neuropathy, memory challenges and balance problems but also emotional symptoms that may exacerbate these. We’re looking at the illnesses or events that can be a sign FXTAS is starting.

When the study began in 1999, we were mainly focused on younger people with the premutation. We began focusing on FXTAS about 15 years ago. We are meeting with them about every two years so we can follow their progression and to see what therapies and treatments may help.

Might it be possible in the future to predict that someone will develop FXTAS?

It’s possible. Better understanding the “pre-FXTAS” stage is very important. We are looking for biomarkers that could help with that goal. For instance, are there biomarkers that will tell us whether someone has white matter disease? And does the degree of white matter disease correlate with motor or mental health challenges? The interplay among these domains in the phenotype are important as we strive to help our patients.

What are some of the things you’re measuring or testing?

We do a special MRI brain scan protocol that shows the degree of white matter disease in the brain. We measure brain volume in different parts of the brain, too. We also look at the degree of tremor and balance problems that they have and assess their gait. We have them walk while doing mental calculations because sometimes that causes more balance difficulties. We also measure reaction time and grip strength and assess for depression or anxiety. And we give them recommendations about what might help them, including exercise, nutrition or medications that their primary care doctor might consider.

What are the key takeaways from this study over the years?

One thing we’ve learned is that premutation challenges can be lifelong. Not necessarily FXTAS, which happens with aging, but there can be neurodevelopmental challenges, including autism, that can occur in a subset of premutation carriers. There are also psychiatric conditions like depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behavior and chronic fatigue, which can occur in mid-adulthood. The premutation is also the most common single-gene cause of ovarian insufficiency, which causes infertility or early menopause. This is a condition we call fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency, or FXPOI.

In fact, women are often tested by their gynecologist and then when we investigate the family tree, we find out their father or mother may have FXTAS. That’s mainly how we find people with FXTAS — either the grandparents of a child with fragile X syndrome or the parent of a woman with the premutation who has FXPOI.

Are there better treatments on the horizon for FXTAS?

I feel very positive about potential future treatments. For example, we recently did a study about sulforaphane, a sulfur-containing protein in broccoli, brussels sprouts and cauliflower. It turns on the Nrf2 gene, which controls the pathways to relieve oxidative stress in the neurons. This was helpful for some cognitive problems with FXTAS. We are also focused on exercise, which can help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress. But we need a better primary treatment for FXTAS. That’s why we’re excited about finding biomarkers in these studies that will lay the groundwork for treatment trials. I believe the next few years could bring about new treatments for FXTAS.

How far has the field of research come since you discovered FXTAS in 2001?

It is now an entity that has worldwide interest and hundreds of papers have been published about it by scientists around the world. But there are still clinicians that I meet who have not heard of FXTAS — even neurologists.

I see patients from all over the world at the MIND Institute, but there are still providers elsewhere who confuse FXTAS with fragile X syndrome, though they are two very different conditions. We must keep building awareness. My MIND Institute colleagues and I recently hosted a conference on the FMR1 premutation in New Zealand which included researchers from all over the world who are studying this, and I am very hopeful for the future.

What drives you to continue this work?

I truly want to find better treatments for FXTAS and all fragile-X associated conditions. You can help a whole family through multiple generations once you make the diagnosis with one or two members in a family. Also, these conditions occur all over the world. I love to bring new treatments and awareness to other places. We do such great work at the MIND Institute, and I want to share that with people all over the world.

END

NIH renews UC Davis MIND Institute grant to study fragile X-associated syndromes for 24th year

World-renowned researcher Randi Hagerman reflects on two decades of research and why she’s hopeful for future treatments

2023-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI must not worsen health inequalities for ethnic minority populations

2023-07-20

Scientists are urging caution before artificial intelligence (AI) models such as ChatGPT are used in healthcare for ethnic minority populations. Writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, epidemiologists at the University of Leicester and University of Cambridge say that existing inequalities for ethnic minorities may become more entrenched due to systemic biases in the data used by healthcare AI tools.

AI models need to be ‘trained’ using data scraped from different sources such as healthcare websites and scientific research. However, evidence shows ...

Monitoring T cells may allow prevention of type 1 diabetes

2023-07-20

LA JOLLA, CA—Scripps Research scientists have shown that analyzing a certain type of immune cell in the blood can help identify people at risk of developing type 1 diabetes, a life-threatening autoimmune disease. The new approach, if validated in further studies, could be used to select suitable patients for treatment that stops the autoimmune process—making type 1 diabetes a preventable condition.

In the study, which appeared in Science Translational Medicine on July 5, 2023, the researchers ...

Important groups of phytoplankton tolerate some strategies to remove CO2 from the ocean

2023-07-20

Humanity has a long track record of making big changes with little forethought. From fossil fuels to AI, plastics to pesticides, we love innovating away our problems, only to find we’ve created different ones. So it can be refreshing to hear about cases where we’ve taken a step back to deliberate before committing to a drastic new idea, like carbon dioxide removal.

With carbon emissions continuing to climb, many scientists, environmentalists and policy-makers have advocated taking action to directly ...

Private equity takeovers of healthcare services linked to patient harm

2023-07-20

Private equity ownership of healthcare services such as nursing homes and hospitals is associated with harmful impacts on costs and quality of care, suggests a review of the latest evidence published by The BMJ today.

No consistently beneficial impacts of private equity ownership were identified, and the researchers say these results confirm the need for more research on private equity ownership in healthcare and possibly increased regulation.

Private equity firms use capital from wealthy individuals and large institutional investors to buy companies, and, after a relatively brief period of ownership, ...

Disrupted access to healthcare during pandemic linked to avoidable hospital admissions

2023-07-20

People who experienced disrupted access to healthcare (including appointments and procedures) during the covid-19 pandemic were more likely to have potentially preventable hospital admissions, finds a study published by The BMJ today.

This is the first study to examine the impact of disruption on health outcomes using individual level longitudinal data, and the researchers say reducing the backlog from covid-19 disruption is vital to tackle the short and long term implications of the pandemic.

The ...

Exposure to antiseizure medications does not harm neurological development in young children

2023-07-20

PITTSBURGH, July 19, 2023 — Most mothers who took prescription antiseizure medications during pregnancy can breathe a sigh of relief: A new study published today in Lancet Neurology found that young children who were exposed to commonly-prescribed medications in utero do not have worse neurodevelopmental outcomes than children of healthy women.

Commonly used antiseizure medications such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam are generally considered effective and safe, especially compared to many first-generation epilepsy treatments that carried profound risks to the unborn child. ...

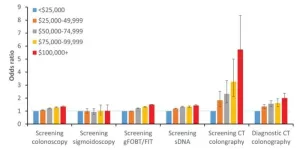

AJR on sociodemographic factors and screening CTC among Medicare beneficiaries

2023-07-20

Leesburg, VA, July 19, 2023—According to an accepted manuscript published in the American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), lacking Medicare coverage could contribute to greater income-based differences in use of screening CT colonography (CTC) than of other recommended screening strategies or of diagnostic CTC.

Noting that Medicare’s non-coverage for screening CTC may account for lower adherence with screening guidelines among lower-income beneficiaries, “Medicare coverage of CTC could reduce income-based disparities for individuals avoiding optical colonoscopy due to invasiveness, need for anesthesia, or complication ...

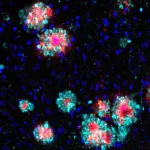

Study sheds light on cellular interactions that lead to liver transplant survival

2023-07-20

A new study identifies how certain proteins in the immune system interact leading to organ rejection. The study, which involved experiments on mice and human patients, uncovered an important communication pathway between two molecules called CEACAM1 (CC1) and TIM-3, finding that the pathway plays a crucial role in controlling the body's immune response during liver transplantation.

When an organ is transplanted from a donor to a recipient, the recipient's immune system recognizes the transplanted tissue as foreign, activating an immune response that can lead to rejection. T cells play a significant role ...

A potential new biomarker for Alzheimer’s

2023-07-20

Alzheimer’s is considered a disease of old age, with most people being diagnosed after 65. But the condition actually begins developing out of sight many years before any symptoms emerge. Tiny proteins, known as amyloid-beta peptides, clump together in the brain to form plaques. These plaques lead to inflammation and eventually cause neuronal cell death.

Interplay of proteins in the brain reveals disease mechanism

Exactly what triggers these pathological changes is still unclear. “We’re lacking good diagnostic markers that would allow us to reliably detect the disease at an early stage or make predictions about its course,” says Professor ...

A non-covalent bonding experience

2023-07-19

UPTON, NY—Putting a suite of new materials synthesis and characterization methods to the test, a team of scientists from the University of Iowa and the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory has developed 14 organic-inorganic hybrid materials, seven of which are entirely new. These uranium-based materials, as well as the detailed report of their bonding mechanisms, will help advance clean energy solutions, including safe nuclear energy. The work, currently published online, was recognized as both a Very Important Paper and a Hot Topic: Crystal Engineering in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

Heat does not reduce prosociality

Advancing brain–computer interfaces for rehabilitation and assistive technologies

Detecting Alzheimer's with DNA aptamers—new tool for an easy blood test

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal study develops radiomics model to predict secondary decompressive craniectomy

New molecular switch that boosts tooth regeneration discovered

Jeonbuk National University researchers track mineral growth on bioorganic coatings in real time at nanoscale

Convergence in the Canopy: Why the Gracixalus weii treefrog sounds like a songbird

Subway systems are uncomfortably hot — and worsening

Granular activated carbon-sorbed PFAS can be used to extract lithium from brine

[Press-News.org] NIH renews UC Davis MIND Institute grant to study fragile X-associated syndromes for 24th yearWorld-renowned researcher Randi Hagerman reflects on two decades of research and why she’s hopeful for future treatments