(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — There’s a barrier preventing the advent of truly elastic electronic systems, the kind needed for advanced human-machine interfaces, artificial skins, smart health care and more, but a Penn State-led research team may have found a way to stretch around it.

According to principal investigator Cunjiang Yu, who holds is the Dorothy Quiggle Career Development Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics and of Biomedical Engineering at Penn State, fully elastic electronic systems require flexibility and stretchability in every component. Researchers have achieved this characteristic in most of the components, except for one type of semiconductor that is notoriously brittle. Now, Yu and his international team developed an approach to compensate for the frail and breakable semiconductor to advance the field closer to fully flexible systems.

They published their work in Nature Electronics.

“Such technology requires stretchy elastic semiconductors, the core material needed to enable integrated circuits that are critical to the technology enabling our computers, phones and so much more, but these semiconductors are mainly p-type,” said Yu, referring to a material that conducts electricity primarily through positively charged movable holes. “However, complementary integrated electronics, optoelectronics, p-n junction devices and many others — also require an n-type semiconductor.”

N-type semiconductors conduct electricity primarily through negative electrons carrying the charge, and in combination with p-type semiconductors, they can act as a switch, with current flowing in one direction. They are often rigid, and certain strategies to make them more mechanically stretchy are needed to achieve completely stretchable transistors and circuits with n-type semiconductors, according to Yu.

To address this issue, the researchers sandwiched the n-type semiconductor between two rubbery materials known as elastomers, which are polymers that can stretch and snap back to their original shape.

“We found that the stack architecture improves mechanical stretchability and suppresses the formation and propagation of microcracks in the intrinsically brittle n-type semiconductor,” Yu said, explaining that microcracks are tiny structure defects that appear when the n-type semiconductor is stretched. They can degrade electrical performance and lead to mechanical failure.

The team put the stack through a gauntlet of stress and stability tests, all of which it passed with flying colors, Yu said. They also used the stack to fabricate stretchy transistors and integrated electronic systems.

“The elastic transistors retained high device performance even when stretched 50% in either direction,” Yu said. “The devices also exhibited long-term stable operation for over 100 days in an ambient environment.”

The stability in an ambient environment is particularly useful, according to Yu, because n-type semiconductors can lose efficiency with exposure to oxygen and moisture. Sandwiched between elastomers, the semiconductor is effectively encapsulated against the elements.

Next, Yu said, the team will continue to work to improve the performances of the stacked materials and optimize the layer configuration to further reduce the density of microcracks.

“Now we have a stretchy n-type semiconductor, and we will soon have stretchy rubbery integrated circuits,” Yu said. “Isn’t it exciting?”

Yu is also affiliated with Penn State’s Materials Research Institute and the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences. Penn State Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics graduate students Shubham Patel and Seonmin Jang and former postdoctoral researcher Hyunseok Shim, now affiliated with Pusan National University in Korea, co-authored the paper, along with Yu’s former students at the University of Houston Kyoseung Sim and Yongcao Zhang; Binghao Wang, Southeast University in China; and Torbin J. Marks and Antonio Facchetti, Northwestern University. Sim is now affiliated with the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in Korea. Facchetti is also affiliated with Flexterra Inc.

The Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and Northwestern University’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center supported this research.

END

Stretchy integrated electronics may be possible with sandwiched semiconductor

2023-07-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Water-scarce cultures value long-term thinking more than their water-rich neighbors do

2023-07-24

Water is the world’s most valuable natural resource. Although a human can survive weeks or even months without food, going as little as three days without water could spell the end. The effects of water scarcity aren’t limited to immediate survival situations, however. Recently published research in Psychological Science suggests that cultures from water-scarce environments tend to be more likely than cultures from water-rich areas to value long-term thinking and to scorn short-term indulgence.

“Individuals from historically water-scarce climates tend to be ...

New method for noninvasive detection of circulating tumor cells in blood

2023-07-24

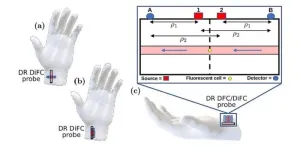

Metastasis occurs when cancer cells acquire the ability to spread and form new tumors in different places in the body, usually by traveling within blood or lymph vessels. Since metastasis is a hallmark of advanced cancer and severely complicates treatment, its early diagnosis is essential. One way to do this is by looking for circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood samples.

However, CTCs can be very rare, and they might be completely absent in small blood samples despite being present in a patient’s bloodstream. To address this problem, researchers have developed a technique called diffuse in-vivo flow cytometry (DiFC). It involves labeling CTCs with ...

Colorado River Basin has lost water equal to Lake Mead due to climate change

2023-07-24

American Geophysical Union

Release No. 23-28

24 July 2023

For Immediate Release

This press release and accompanying multimedia are available online at: https://news.agu.org/press-release/colorado-river-basin-has-lost-water-equal-to-lake-mead-due-to-climate-change/

Colorado River Basin has lost water equal to Lake Mead due to climate change

A rapid rate of reductions in runoff associated with the Colorado Basin’s snowpack region, quantified here for the first time, is largely responsible for the water loss.

AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, news@agu.org +1 (202) 777-7492 (UTC-4 hours)

Contact ...

Beyond protected areas: Novel method shows promise for monitoring biodiversity on working lands

2023-07-24

New research led by Adam Dixon, a conservation scientist with the World Wildlife Fund, describes the successful pilot of a novel method to study how well grassland birds are faring on croplands. The study, published in Ecological Applications, looked at 44 pockets of non-crop vegetation in the gaps between crop rows and at the edges of fields on lands under intensive agricultural cultivation in Iowa. The study may serve as a model for monitoring wildlife on working lands more generally, which can include crop fields, cattle ranches, and logged forests.

The researchers analyzed satellite imagery data to determine each pocket's area and “texture,” ...

Is snacking bad for your health? It depends on what and when you eat

2023-07-24

Snacking is becoming increasingly popular, with more than 70% of people reporting they snack at least twice a day. In a new study involving more than 1,000 people, researchers examined whether snacking affects health and if the quality of snack foods matters.

“Our study showed that the quality of snacking is more important than the quantity or frequency of snacking, thus choosing high quality snacks over highly processed snacks is likely beneficial,” said Kate Bermingham, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at King's College London. “Timing is also important, with late night snacking being unfavorable for health.”

Bermingham ...

One way to reduce medical errors? Connect doctors with other doctors

2023-07-24

We trust our doctors with our lives, but the sad and scary fact is that doctors can get things wrong. Approximately 100,000 Americans die each year due to medical errors and recent studies have found that 10 to 15% of all clinical decisions regarding patient diagnosis and treatment are wrong.

A team of researchers led by Damon Centola, Professor and Director of the Network Dynamics Group at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, has found a simple, effective way to reduce errors in patient diagnosis and treatment — use structured networks to connect clinicians with other clinicians.

In a study published today in the journal ...

Study finds new, unexpected mechanism of cancer cell spread

2023-07-24

A surprising finding from USC reveals key details about how cancer cells metastasize and suggests new therapeutic approaches for halting their spread.

The research, supported by the National Institutes of Health, centers on a cellular chaperone protein known as GRP78, which helps regulate the folding of other proteins inside cells. Previous studies from the same team, led by Amy S. Lee, PhD, professor of biochemistry and molecular medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, have shown that when cells are under stress (due to COVID-19 or cancer), GRP78 gets hijacked, allowing viral invaders to replicate, ...

Sahara dust can enhance removal of methane

2023-07-24

The study by Maarten van Herpen et al., entitled “Photocatalytic Chlorine Atom Production on Mineral Dust-Sea Spray Aerosols over North Atlantic,” was funded in part by the NGO Spark Climate Solutions. It incorporates a proposed new mechanism whereby blowing mineral dust mixes with sea-spray to form Mineral Dust-Sea Spray Aerosol (MDSA).

The results suggest that MDSA is activated by sunlight to produce an abundance of chlorine atoms, which oxidize atmospheric methane and tropospheric ozone via photocatalysis. Largely composed of blowing dust from the Sahara Desert combined with sea salt aerosol from the ocean, MDSA is the dominant source of atmospheric ...

Unlocking secrets of the elusive ghost shark

2023-07-24

Researchers from the University of Florida and the Seattle Aquarium are exploring 100 meters underwater in the Pacific Northwest this summer to learn more about mysterious ghost sharks, one of the strangest beasts from the depths of the ocean.

Using remotely operated underwater vehicles, or ROVs, the scientists searched for nesting grounds of the Pacific spotted ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei, a ghostlike fish that lurks on the ocean floor.

“We know very little about these elusive relatives of sharks and even less about their spawning habits and embryonic development,” said ...

Risk of fatal heart attack may double in heat wave & high fine particulate pollution days

2023-07-24

Research Highlights:

An analysis of more than 202,000 heart attack deaths between 2015-2020 in a single Chinese province found that days that had extreme heat, extreme cold or high levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution were significantly associated with the risk of death from a heart attack, especially in women and older adults.

The greatest increase in the risk of death from heart attack was seen on days that had the combination of extreme heat and high levels of PM2.5.

The days with extreme heat were associated ...