AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, news@agu.org (UTC-4 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Matthew S. Huber, University of the Western Cape, mhuber@uwc.ac.za (UTC+2 hours)

WASHINGTON — Earth’s oldest craters could give scientists critical information about the structure of the early Earth and the composition of bodies in the solar system as well as help to interpret crater records on other planets. But geologists can’t find them, and they might never be able to, according to a new study. The study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research Planets, AGU’s journal for research on the formation and evolution of the planets, moons and objects of our Solar System and beyond.

Geologists have found evidence of impacts, such as ejecta (material flung far away from the impact), melted rocks, and high-pressure minerals from more than 3.5 billion years ago. But the actual craters from so long ago have remained elusive. The planet’s oldest known impact structures, which is what scientists call these massive craters, are only about 2 billion years old. We’re missing two and a half billion years of mega-craters.

The steady tick of time and the relentless process of erosion are responsible for the gap, according to Matthew S. Huber, a planetary scientist at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa who studies impact structures and led the new study.

“It’s almost a fluke that the old structures we do have are preserved at all,” Huber said. “There are a lot of questions we’d be able to answer if we had those older craters. But that’s the normal story in geology. We have to make a story out of what’s available.”

Geologists can sometimes spot hidden, buried craters using geophysical tools, such as seismic imaging or gravity mapping. Once they’ve identified potential impact structures, they can search for physical remnants of the impact process to confirm its existence, such as ejecta and impact minerals.

The big question for Huber and his team was how much of a crater can be swept away by erosion before the last lingering geophysical traces disappear. Geophysicists have suggested that 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of vertical erosion would erase even the biggest impact structures, but that threshold had never been tested in the field.

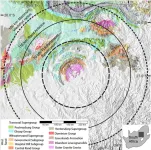

To find out, the researchers dug into one of the planet’s oldest known impact structures: the Vredefort crater in South Africa. The structure is about 300 kilometers (186 miles) across and was formed about 2 billion years ago when an impactor about 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) across slammed into the planet.

The impactor hit with such energy that the crust and mantle rose up where the impact occurred, leaving a long-term dome. Farther from the center, ridges of rock jutted up, minerals transformed and rock melted. And then time took its course, eroding about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) down from the surface in two billion years.

Today, all that remains at the surface is a semicircle of low hills southwest of Johannesburg, which marks the center of the structure, and some smaller, telltale signs of impact. The bullseye, caused by the uplift of the mantle, appears in gravity maps, but beyond the center, geophysical evidence of the impact is lacking.

“That pattern is one of the last geophysical signatures that is still detectable, and that only happens for the largest-scale impact structures,” Huber said. Because only the deepest layers of the structure remain, the other geophysical traces have disappeared.

But that’s okay, because Huber wanted to know just how reliable those deep layers are for recording ancient impacts from both a mineralogical and geophysical perspective.

“Erosion makes these structures disappear from the top down,” Huber said. “So we went from the bottom up.”

The researchers sampled rock cores across a 22-kilometer (13.7-mile) transect and analyzed their physical properties, searching for differences in density, porosity and mineralogy between impacted and non-impacted rocks. They also modeled the impact event and what its effects on rock and mineral physics would be and compared that to what they saw in their samples.

What they found was not encouraging for the search for Earth’s oldest craters. While some impact melt and minerals remained, the rocks in the outer ridges of the Vredefort structure were essentially indistinguishable from the non-impact rocks around them when viewed through a geophysical lens.

“That was not exactly the result we were expecting,” Huber said. “The difference, where there was any, was incredibly muted. It took us a while to really make sense of the data. Ten kilometers of erosion and all the geophysical evidence of the impact just disappears, even with the largest craters,” confirming what geophysicists had estimated previously.

The researchers caught Vredefort just in time; if much more erosion occurs, the impact structure will be gone. The odds of finding buried impact structures from more than 2 billion years ago are low, Huber said.

“In order to have an Archean impact crater preserved until today, it would have to have experienced really unusual conditions of preservation,” Huber said. “But then, Earth is full of unusual conditions. So maybe there’s something unexpected somewhere, and so we keep looking.”

#

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

***

Notes for journalists:

This paper is published in JGR Planets with open access. View and download a PDF of the study here.

Paper title:

“Can Archean impact structures be discovered? A case study from Earth’s largest, most deeply eroded impact structure”

Authors:

Matthew S. Huber (corresponding author), Department of Earth Science, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

E. Kovaleva, Department of Earth Science, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa; Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, GFZ, Potsdam, Germany

A.S.P. Rae, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

N. Tisato, Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geoscience, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, US; Center for Planetary Systems Habitability, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, US

S.P.S. Gulick, Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geoscience, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, US; Center for Planetary Systems Habitability, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, US; Institute for Geophysics, Jackson School of Geoscience, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, US END