(Press-News.org) Carbon dioxide levels in Earth’s atmosphere — and, consequently, ocean temperatures — are rising. How high and how fast ocean temperatures can rise can be learned from temperature measurements of ancient oceans. At the same time, energy exploration also relies on knowing the thermal history of oil and gas source rocks, which is often difficult to determine.

One of the most promising techniques for measuring ancient ocean temperatures and basin thermal histories relies on the co-enrichment of rare heavy oxygen and heavy carbon in the calcium carbonate compound found at the bottom of the ocean. This enrichment, termed clumped isotopes, is commonly measured using fossil shells and limestones to determine the temperatures at the time when sediments became deposited on the sea floor.

However, there’s a catch: Clumped isotope temperatures can be reset by the very process of sediments being buried, causing those sediment temperatures to rise as they create the same conditions responsible for converting organic matter in sedimentary rocks to oil.

Such complex problems require interdisciplinary approaches — a collaborative mindset that thrives in the Texas A&M University College of Arts and Sciences, where a team of geologists and chemists has taken the quest to the atomic level to more accurately measure ancient ocean temperatures.

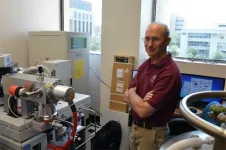

The team, led by Dr. Ethan Grossman in the Department of Geology and Geophysics and Dr. Sarbajit Banerjee in the Department of Chemistry, recently used a combination of supercomputing and density functional theory to model the process responsible for setting and resetting clumped isotope compositions, a phenomenon known as reordering.

“We were able to vividly simulate the motion of atoms and to capture the entire process underpinning rearrangement of carbon-oxygen bonds,” said Grossman, holder of the Michel T. Halbouty Chair and co-director of the Stable Isotope Geosciences Facility at Texas A&M. “This modeling technique, commonly applied to simulate the behavior of atoms in many scenarios, including lithium-ion batteries and brain-like computing, is for the first time being used to examine the rare movement of atoms in fossil shells and limestone rock.”

In comparing their results to previously published experimental results, Grossman says the team was also able to provide the missing link between experimentation and theory in identifying the catalytic culprit responsible for speeding up temperature resets in those clumped isotopes: water.

“We theoretically demonstrated for the first time that water in the crystal structure will hasten the resetting of clumped isotope temperatures, which thus warrants caution for how the approach is used to reconstruct ancient temperature records,” Grossman added. “This supports experimental data that previously lacked a theoretical underpinning and will lead to more accurate reconstructions of past climates, which in turn provides understanding of future climate scenarios.”

In addition to identifying the role of water as an accelerant in reordering, Grossman says the team’s studies help explain other enigmatic results — notably, the modification of fossil-derived ocean temperatures to impossibly high values hovering around 150 degrees Celsius, or roughly 300 degrees Fahrenheit. They were able to determine such outliers using specimens from approximately 320-million-year-old marine sedimentary rock deeply buried in the past and now exposed in New Mexico and the Ural Mountains in Russia.

“Clearly, these organisms did not live in water hotter than boiling temperatures,” he explained. “This finding pointed to the need to understand the burial history of fossils and the rates of clumped isotope reordering.”

The team’s results, published earlier this summer in Science Advances, represent a pivotal first step in developing a unified theory for the clumped-isotope reordering kinetics in carbonate minerals that Grossman says will pave the way for more accurate determinations of ancient ocean temperatures and the thermal history of petroleum basins. By illustrating how activation energy barriers and reordering rates are modified by crystal defects, ion substitution and incorporated water, they hope to contribute to more accurate reconstructions of past climates and a clearer understanding of future climate scenarios while also providing a mechanism for reconstructing the thermal history of sedimentary basins essential for oil and gas exploration.

“This study will allow for more accurate reconstructions of past climates by better understanding the depths of sediment burial beyond which clumped isotope temperatures from fossil shells are unreliable,” Grossman said. “Furthermore, it demonstrates the value of collaboration between departments and fields that have not traditionally worked together to unveil fundamentally new knowledge.”

In addition to Grossman and Banerjee, the team’s paper featured three lead co-authors: 2021 Texas A&M chemical engineering Ph.D. graduate Dr. Saul Perez-Beltran '20, who currently is a postdoctoral researcher with the Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station; 2023 Texas A&M materials and analytical chemistry Ph.D. graduate Dr. Wasif Zaheer '19, now a senior research specialist with Dow; and current Texas A&M geology candidate Zeyang Sun '19. The University of Queensland’s Dr. William F. Defliese, formerly a Berg-Hughes Postdoctoral Fellow at Texas A&M from 2017-2019, also was involved in the work.

The team’s paper, “Density Functional Theory and Ab-Initio Molecular Dynamics Reveal Atomistic Mechanisms for Carbonate Clumped Isotope Reordering,” can be viewed online along with related figures and acknowledgements. Their research was funded by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. EAR-19115647), with additional support from The Welch Foundation (Grant No. A-A1978-20220331), the Michel T. Halbouty Chair in Geology and the Chancellor’s Research Initiative for Mass Spectrometry, established in 2016.

“We have many unanswered questions,” Grossman said. “For starters, how does this reordering rate vary with the amount of water in the crystal structure? How does it vary in different minerals? Can we develop protocols for identifying the fossil and mineral material most resistant to reordering? Can we define a calibration scale to correct for errors in each mineral? And lastly, can we use this information to develop a new and innovative approach to reconstruct basin thermal histories and refine oil and gas exploration? In sum, we are eager for our next steps.”

END

Texas A&M chemists, geologists bond over NSF-funded study of clumped isotopes

2023-08-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Minds & eyes: Study shows dementia more common in older adults with vision issues

2023-08-01

Losing the ability to see clearly, and losing the ability to think or remember clearly, are two of the most dreaded, and preventable, health issues associated with getting older.

Now, a new study lends further weight to the idea that vision problems and dementia are linked.

In a sample of nearly 3,000 older adults who took vision tests and cognitive tests during home visits, the risk of dementia was much higher among those with eyesight problems – including those who weren’t able ...

John Rummel to be honored with the SETI Institute’s 2023 Drake Award

2023-08-01

August 1, 2023, Mountain View, CA – The SETI Institute is proud to announce that Dr. John Rummel will receive the prestigious 2023 Drake Award, recognizing his extraordinary and innovative programmatic contributions and unwavering advocacy for SETI and astrobiology. Rummel’s illustrious career has included roles at NASA Headquarters, where he served as Senior Scientist for Astrobiology, Planetary Protection Officer, Deputy Chief of the Mission from Planet Earth Study Office, and Program Scientist for SETI/High Resolution Microwave Survey. Despite sometimes facing significant opposition, Rummel has been an unwavering supporter of SETI science and funding, working to ...

Beatson Foundation awards grant to Boston College biologist Emrah Altindis for Type 1 diabetes research

2023-08-01

Chestnut Hill, Mass. (08/01/2023 - Boston College Assistant Professor of Biology Emrah Altindis has received a two-year, $275,000-grant from the Beatson Foundation to explore the role of gut microbes and viruses triggering the autoimmunity of Type 1 diabetes.

“Our lab is extremely grateful for the generous funding bestowed upon us by the Beatson Foundation,” Altindis said. “The receipt of this grant has evoked a profound sense of both excitement and gratitude within our team. We recognize the significant impact this funding will have on our research endeavors, particularly in the field of Type 1 Diabetes.”

Funding for the project, titled ...

North Atlantic Oscillation contributes to ‘cold blob' in Atlantic Ocean

2023-08-01

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A patch of ocean in the North Atlantic is stubbornly cooling while much of the planet warms. This anomaly — dubbed the "cold blob" — has been linked to changes in ocean circulation, but a new study found changes in large-scale atmospheric patterns may play an equally important role, according to an international research team led by Penn State.

“People often think the atmosphere has a very short memory, but here we provide evidence that atmospheric circulation change is significant enough to induce some long-term impact on the climate system,” ...

MSU leads Office of Naval Research grant to make AI more reliable and transparent

2023-08-01

Highlights:

Michigan State University researchers are leading a $1.8 million grant project funded by the Office of Naval Research to evolve artificial intelligence.

The research would make it possible to use AI more reliably for tasks we already accomplish with help from popular AI tools like ChatGPT. It could also enable people to entrust AI systems with more advanced jobs that rely on understanding language and visual information, including education, navigation and multimodal question-answering systems.

The team is working to connect “classical” or symbolic AI with current deep neural networks and create a neuro-symbolic framework. ...

Multiclonality of estrogen receptor expression in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

2023-08-01

“We have discussed in detail the clinical implications of ER in avoiding overtreatment and undertreatment in DCIS.”

BUFFALO, NY- August 1, 2023 – A new editorial paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on July 20, 2023, entitled, “Multiclonality of ER expression in DCIS – Implications for clinical practice and future research.”

Estrogen receptor (ER) expression is not routinely evaluated in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). This may be because the prognostic role of ER in DCIS was unclear until the UK/ ANZ DCIS trial in 2021 showed that lack of ER expression in DCIS was associated with a greater than 3-fold risk of ipsilateral recurrence. This ...

Score, then rank: Researchers propose an integrated approach to grant review assessments

2023-08-01

The public funding of science is responsible for many of the biomedical and other scientific breakthroughs on which our lives depend. However, the process through which funding decisions are made, the peer review of grant proposals, has been historically understudied, and current approaches can lead to undesirable outcomes. Writing in Research Integrity and Peer Review, Stephen A. Gallo, then affiliated with the American Institute of Biological Sciences, and Michael Pearce, Carole J. Lee, and Elena A. Erosheva from the University of ...

A floating sponge could help remove harmful algal blooms

2023-08-01

In the peak heat of summer, beachgoers don’t want their plans thwarted by harmful algal blooms (HABs). But current methods to remove or kill toxin-producing algae and cyanobacteria aren’t efficient or practical for direct applications in waterways. Now, researchers reporting in ACS ES&T Water have coated a floating sponge in a charcoal-like powder, and when paired with an oxidizing agent, the technique destroyed over 85% of algal cells from lake and river water samples.

Swaths of electric green and bright orange-red HABs, or the less brilliantly colored cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa, can produce toxins that can sicken humans ...

Early-life lead exposure linked to higher risk of criminal behavior in adulthood

2023-08-01

An evaluation of 17 previously published studies suggests that exposure to lead in the womb or in childhood is associated with an increased risk of engaging in criminal behavior in adulthood—but more evidence is needed to strengthen understanding. Maria Jose Talayero Schettino of the George Washington University, U.S., and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Global Public Health.

Lead exposure can cause a variety of health challenges, such as cardiac issues, kidney ...

Organoids revolutionize research on respiratory infections

2023-08-01

Biofilms are highly resistant communities of bacteria that pose a major challenge in the treatment of infections. While studying biofilm formation in laboratory conditions has been extensively conducted, understanding their development in the complex environment of the human respiratory tract has remained elusive.

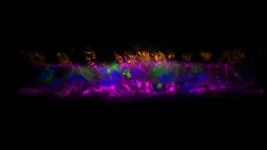

A team of researchers led by Alexandre Persat at EPFL have now cracked the problem by successfully developing organoids called AirGels. Organoids are miniature, self-organized 3D tissues grown from stem cells to mimic actual body tissues and organs in the human body. They represent ...