(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- A few years ago while on a fishing trip in the Florida Keys, biologist Lori Schweikert came face to face with an unusual quick-change act. She reeled in a pointy-snouted reef fish called a hogfish and threw it onboard. But later when she went to put it in a cooler she noticed something odd: its skin had taken on the same color and pattern as the deck of the boat.

A common fish in the western Atlantic Ocean from North Carolina to Brazil, the hogfish is known for its color-changing skin. The species can morph from white to mottled to reddish-brown in a matter of milliseconds to blend in with corals, sand or rocks.

Still, Schweikert was surprised because this hogfish had continued its camouflage even though it was no longer alive. Which got her wondering: can hogfish detect light using only their skin, independently of their eyes and brain?

“That opened up this whole field for me,” Schweikert said.

In the years that followed, Schweikert started researching the physiology of “skin vision” as a postdoctoral fellow at Duke University and Florida International University.

In 2018, Schweikert and Duke biologist Sönke Johnsen published a study showing that hogfish carry a gene for a light-sensitive protein called opsin that is activated in their skin, and that this gene is different from the opsin genes found in their eyes.

Other color-changing animals from octopuses to geckos have been found to make light-sensing opsins in their skin, too. But exactly how they use them to help change color is unclear.

“When we found it in hogfish, I looked at Sönke and said: Why have a light detector in the skin?” said Schweikert, now an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

One hypothesis is that light-sensing skin helps animals take in their surroundings. But new findings suggest another possibility -- “that they could be using it to view themselves,” Schweikert said.

In a study appearing Aug. 22 in the journal Nature Communications, Schweikert, Johnsen and colleagues teamed up to take a closer look at hogfish skin.

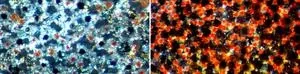

The researchers took pieces of skin from different parts of the fish’s body and took pictures of them under a microscope.

Up close, a hogfish’s skin looks like a pointillist painting. Each dot of color is a specialized cell called a chromatophore containing granules of pigment that can be red, yellow or black.

It’s the movement of these pigment granules that changes the skin color. When the granules spread out across the cell, the color appears darker. When they cluster together into a tiny spot that’s hard to see, the cell becomes more transparent.

Next, the researchers used a technique called immunolabeling to locate the opsin proteins within the skin. They found that in the hogfish, opsins aren’t produced in the color-changing chromatophore cells. Instead, the opsins reside in other cells directly beneath them.

Images taken with a transmission electron microscope revealed a previously unknown cell type, just below the chromatophores, packed with opsin protein.

This means that light striking the skin must pass through the pigment-filled chromatophores first before it reaches the light-sensitive layer, Schweikert said.

The researchers estimate that the opsin molecules in hogfish skin are most sensitive to blue light. This happens to be the wavelength of light that the pigment granules in the fish’s chromatophores absorb best.

The findings suggest that fish’s light-sensitive opsins act somewhat like internal Polaroid film, capturing changes in the light that is able to filter through the pigment-filled cells above as the pigment granules bunch up or fan out.

“The animals can literally take a photo of their own skin from the inside,” Johnsen said. “In a way they can tell the animal what it’s skin looks like, since it can’t really bend over to look.”

“Just to be clear, we're not arguing that hogfish skin functions like an eye,” Schweikert added. Eyes do more than merely detect light -- they form images. “We don't have any evidence to suggest that's what's happening in their skin,” Schweikert said.

Rather, it’s a sensory feedback mechanism that lets the hogfish monitor its own skin as it changes color, and fine-tune it to fit what it sees with its eyes.

“They appear to be watching their own color change,” Schweikert said.

The researchers say the work is important because it could pave the way to new sensory feedback techniques for devices such as robotic limbs and self-driving cars that must fine-tune their performance without relying solely on eyesight or camera feeds.

“Sensory feedback is one of the tricks that technology is still trying to figure out,” Johnsen said. “This study is a nice dissection of a new sensory feedback system.”

“If you didn't have a mirror, and you couldn't bend your neck, how would you know if you're dressed appropriately?” Schweikert said. “For us it may not matter,” she added. But for creatures that use their color-changing abilities to hide from predators, warn rivals or woo mates, “it could be life or death.”

The study was co-authored by researchers from the Florida Institute of Technology, Florida International University, and the Air Force Research Laboratory. Financial support came from Duke University, Florida International University, the Marine Biological Laboratory and the National Science Foundation (1556059).

CITATION: "Dynamic Light Filtering Over Dermal Opsin as a Sensory Feedback System in Fish Color Change," Lorian E. Schweikert, Laura E. Bagge, Lydia F. Naughton, Jacob R. Bolin, Benjamin R. Wheeler, Michael S. Grace, Heather D. Bracken-Grissom, and Sönke Johnsen. Nature Communications, Aug. 22, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-40166-4

END

This fish doesn't just see with its eyes -- it also sees with its skin.

Now researchers think they know why.

2023-08-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New antibiotic from microbial ‘dark matter’ could be powerful weapon against superbugs

2023-08-22

A new powerful antibiotic, isolated from bacteria that could not be studied before, seems capable to combat harmful bacteria and even multi-resistant ‘superbugs’. Named Clovibactin, the antibiotic appears to kill bacteria in an unusual way, making it more difficult for bacteria to develop any resistance against it. Researchers from Utrecht University, Bonn University (Germany), the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), Northeastern University of Boston (USA), and the company NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, USA) now share the discovery of Clovibactin and its killing mechanism in the scientific journal Cell.

Urgent need for new antibiotics

Antimicrobial ...

Effect of a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction during pregnancy on child neurodevelopment

2023-08-22

About The Study: In this randomized clinical trial that included 626 children, maternal structured lifestyle interventions during pregnancy based on a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction significantly improved child neurodevelopmental outcomes at age 2.

Authors: Francesca Crovetto, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Barcelona in Barcelona, Spain, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30255)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including ...

Comparison of ophthalmologist and AI chatbot responses to online patient eye care questions

2023-08-22

About The Study: In this study of human-written and artificial intelligence (AI)-generated responses to 200 eye care questions from an online advice forum, a chatbot appeared capable of responding to long user-written eye health posts and largely generated appropriate responses that did not differ significantly from ophthalmologist-written responses in terms of incorrect information, likelihood of harm, extent of harm, or deviation from ophthalmologist community standards.

Authors: Sophia Y. Wang, M.D., M.S., of Stanford University in Stanford, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed ...

Hard-of-hearing music fans prefer a different sound

2023-08-22

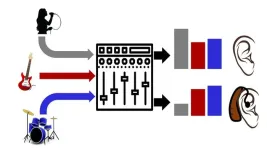

WASHINGTON, August 22, 2023 – Millions of people around the world experience some form of hearing loss, resulting in negative impacts to their health and quality of life. Treatments exist in the form of hearing aids and cochlear implants, but these assistive devices cannot replace the full functionality of human hearing and remain inaccessible for most people. Auditory experiences, such as speech and music, are affected the most.

In JASA, published on behalf of the Acoustical Society of America by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Oldenburg studied the impact of hearing loss on subjects’ enjoyment of different ...

High-fat diets alter gut bacteria, boosting colorectal cancer risk in mice

2023-08-22

LA JOLLA (August 22, 2023)—The prevalence of colorectal cancer in people under the age of 50 has risen in recent decades. One suspected reason: the increasing rate of obesity and high-fat diets. Now, researchers at the Salk Institute and UC San Diego have discovered how high-fat diets can change gut bacteria and alter digestive molecules called bile acids that are modified by those bacteria, predisposing mice to colorectal cancer.

In the study, published in Cell Reports on August 22, 2023, the team found increased levels of specific gut bacteria in mice fed high-fat diets. Those gut bacteria, they ...

BU commentary: Vitamin D supplementation was found to improve more than 1.5 fold survival of cancers of the digestive tract including colorectal cancer in patients with a cancer fighting immune system

2023-08-22

(Boston)—For more than 100 years, it has been believed that sunlight and vitamin D deficiency were associated with the risk for many deadly cancers including colorectal, prostate and breast. But some scientists remained skeptical that this nutrient provides any benefit for reducing cancer risk and morbidity and mortality and several randomized controlled trials that have supported this doubt.

However, in a new commentary in JAMA Network Open, Michael F. Holick, PhD, MD, professor of medicine, pharmacology, physiology & biophysics and molecular medicine at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, explores the controversy as to ...

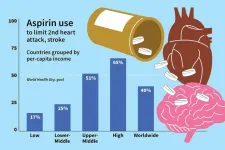

Aspirin can help prevent a second heart attack, but most don’t take it

2023-08-22

For people who have experienced a heart attack or stroke, taking a daily aspirin has been shown to help prevent a second one. Yet, despite aspirin’s low cost and its clear benefits in such scenarios, fewer than half of people worldwide who have had a heart attack or stroke take the medication, according to a new study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Michigan.

The study appears Aug. 22 in JAMA.

Cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and ...

Poor report card for children’s wellbeing

2023-08-22

While COVID-19 lockdowns are no longer mandated, the stress and anxiety of the pandemic still lingers, especially among young South Australians, say health experts at the University of South Australia.

In a new study released today, researchers show that children’s mental health and wellbeing have gradually worsened over the past six years, particular during and post the pandemic.

Examining measures of wellbeing – life satisfaction, optimism, happiness, cognitive engagement, emotional regulation, perseverance, worry, and sadness – ...

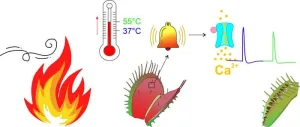

Heat sensor protects the Venus flytrap from fire

2023-08-22

The Venus flytrap can survive in the nutrient-poor swamps of North and South Carolina because it compensates for the lack of nitrogen, phosphate and minerals by catching and eating small animals. It hunts with snap traps that have sensory hairs on them. If an insect touches these hairs two times, the traps shut and digests the prey.

In its location in the swamp, the carnivorous plant is often not visible because it is overgrown by grass. In summer, the grass dries up. Then it can catch fire from the frequent lightning storms typical of North Carolina – ...

Cleveland Clinic-led team awarded $2.8 million to translate cancer cell evolution research to clinical care

2023-08-22

The National Institutes of Health recently awarded Cleveland Clinic’s Jacob Scott, M.D., D.Phil., and collaborators $2.8 million to translate research on how cancer cells evolve and compete into patient care. The project aims to move previous advances done in vitro closer to clinical reality by developing computer and preclinical models side-by-side, a significant step in the fight against multidrug-resistant cancers that are responsible for more than 90% of cancer deaths.

This is a milestone for ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

Frontiers in Science Deep Dive webinar series: How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

UMaine researcher develops model to protect freshwater fish worldwide from extinction

Illinois and UChicago physicists develop a new method to measure the expansion rate of the universe

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

AI-powered platform accelerates discovery of new mRNA delivery materials

Quantum effect could power the next generation of battery-free devices

[Press-News.org] This fish doesn't just see with its eyes -- it also sees with its skin.Now researchers think they know why.