(Press-News.org) More and more bacterial pathogens are developing resistance. There is an increasing risk that common drugs will no longer be effective against infectious diseases. That is why scientists around the world are searching for new effective substances. Researchers from the University of Bonn, the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), Utrecht University (Netherlands), Northeastern University in Boston (USA) and the company NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge (USA) now have discovered and deciphered the mode of action of a new antibiotic. Clovibactin is derived from a soil bacterium. This antibiotic is highly effective at attacking the cell wall of bacteria, including many multi-resistant “superbugs.” The results have now been published in the renowned journal Cell.

“We urgently need new antibiotics to stay ahead in the race against bacteria that have become resistant,” says Prof. Dr. Tanja Schneider of the Institute for Pharmaceutical Microbiology at the University of Bonn and the University Hospital Bonn. She adds that in recent decades, not many new substances to combat bacterial pathogens have come onto the market. “Clovibactin is novel compared to current antibiotics in use,” says the co-spokesperson of the Transregional Collaborative Research Center “Antibiotic CellMAP,” who is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Life & Health” and the Cluster of Excellence “ImmunoSensation2.” The Institute for Pharmaceutical Microbiology, together with the German Center for Infection Research, specializes in deciphering the mode of action of antibiotic candidates.

The soil bacterium Eleftheria terrae subspecies carolina carries its place of origin in its name: It was isolated from a soil sample in the US state of North Carolina and produces the new antibiotic compound clovibactin to protect itself from competing bacteria. “The new antibiotic simultaneously attacks the bacterial cell wall at several sites by blocking essential building blocks,” explains Tanja Schneider. It specifically binds to these building blocks with unusual intensity and kills the bacteria by destroying their cell envelope.

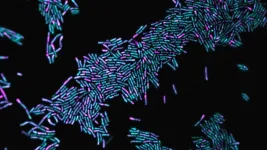

Clovibactin surrounds the target structure like a cage

Research groups from different disciplines and countries worked together to unravel exactly how this works. The team led by Prof. Kim Lewis of the Antimicrobial Discovery Center at Northeastern University in Boston (USA) and the company NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge (USA) discovered clovibactin using the iCHip device. This allows bacteria to be grown in the laboratory that were previously considered unculturable and were not available for the development of new antibiotics.

“Our discovery of this exciting new antibiotic further validates the iCHip culturing technology for finding new therapeutic compounds from previously uncultivated microorganisms,” says Dallas Hughes, Ph.D., president of NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals, LLC. The company has demonstrated that clovibactin has very good activity against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens and has successfully treated mice in preclinical studies.

The mode of action of the new antibiotic was elucidated by researchers led by Tanja Schneider. The researchers from Bonn were able to show that clovibactin binds very selectively and with high specificity to pyrophosphate groups of bacterial cell wall components. Prof. Markus Weingarth’s group from the Department of Chemistry at Utrecht University in the Netherlands uncovered exactly what this interaction looks like. Using solid-state NMR spectroscopy, the researchers deciphered the structure of the complex of clovibactin and the bacterial target structure lipid II - under conditions similar to those found in the bacterial cell. These studies showed that clovibactin grips around the pyrophosphate group. This is where the name “Clovibactin” comes from, derived from the Greek “Klouvi” (cage), because it encloses the target structure like a cage.

Combined attack minimizes resistance development

Clovibactin acts primarily on gram-positive bacteria. These include “hospital pathogens,” such as MRSA bacteria but also the pathogens of the widespread tuberculosis, which affects many millions of people worldwide. “We are very confident that the bacteria will not develop resistance to clovibactin so quickly,” Tanja Schneider says. This is because the pathogens cannot change the cell wall building blocks so easily to undermine the antibiotic - their Achilles’ heel therefore remains.

But clovibactin can do even more. After docking to the target structures, clovibactin forms supramolecular filamentous structures that tightly enclose and further damage the target structures of the bacteria. Bacteria that encounter clovibactin are also stimulated to release certain enzymes, known as autolysins, which then uncontrollably dissolve their own cell envelope. “The combination of these different mechanisms is the reason for the exceptional resilience to resistance,” says Tanja Schneider. This shows the potential that still exists in the natural diversity of bacteria that are candidates for new antibiotics.

“Without the interdisciplinary cooperation between the partners, this important step in the fight against resistance would not have succeeded,” says Prof. Markus Weingarth. The research team now plans to use its findings to further increase the effectiveness of clovibactin. “But there is still a long way to go before a new antibiotic hits the market,” says Tanja Schneider.

Participating institutions and funding:

In addition to the Institute for Pharmaceutical Microbiology and the Clausius Institute for Physical and Theoretical Chemistry at the University of Bonn, participants in this study included Utrecht University (Netherlands), NovoBiotic Pharmaceutical in Cambridge (USA), the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (Netherlands), the University of Tübingen, the German Center for Infection Research, Tianjin Medical University (China), the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Cambridge (USA), the University of Florence (Italy), the Consorzio Interuniversitario Risonanze Magnetiche di Metallo Proteine in Sesto Fiorentino (Italy) and Northeastern University in Boston (USA). The German Center for Infection Research and the Transregional Collaborative Research Center “Antibiotic CellMAP” of the German Research Foundation funded the project on the Bonn and Tübingen side.

Publication: Rhythm Shukla, Aaron J. Peoples, Kevin C. Ludwig, Sourav Maity, Maik G.N. Derks, Stefania De Benedetti, Annika M Krueger, Bram J.A. Vermeulen, Theresa Harbig, Francesca Lavore, Raj Kumar, Rodrigo V. Honorato, Fabian Grein, Kay Nieselt, Yangping Liu, Alexandre Bonvin, Marc Baldus, Ulrich Kubitscheck, Eefjan Breukink, Catherine Achorn, Anthony Nitti, Christopher J. Schwalen, Amy L. Spoering, Losee Lucy Ling, Dallas Hughes, Moreno Lelli, Wouter H. Roos, Kim Lewis, Tanja Schneider, Markus Weingarth: A new antibiotic from an uncultured bacterium binds to an immutable target, Cell, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.07.038

Media contact:

Prof. Dr. Tanja Schneider

Institute for Pharmaceutical Microbiology

University of Bonn and University Hospital Bonn

Tel. +49 (0)228 735688

Email: tschneider@uni-bonn.de

Prof. Dr. Markus Weingarth

Department of Chemistry

Utrecht University

Tel. +31 (0)640828581

Email: m.h.weingarth@uu.nl

END

Researchers decode new antibiotic

Cooperation between the University of Bonn, the USA and the Netherlands cracks the mode of action of clovibactin

2023-08-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Wistar researchers discover potential target for gastric cancers associated with Epstein-Barr virus

2023-08-22

PHILADELPHIA—(August 22, 2023)—Now, scientists at The Wistar Institute have discovered a potential target for gastric cancers associated with Epstein-Barr Virus; study results were published in the journal mBio. In the paper, Wistar’s Tempera lab investigates the epigenetic characteristics of gastric cancer associated with the Epstein-Barr Virus: EBVaGC. In evaluating EBVaGC’s epigenetics — the series of biological signals associated with the genome that determines whether a given gene is expressed — the Tempera lab ...

Advances in quantum emitters mark progress toward a quantum internet

2023-08-22

– By Alison Hatt

The prospect of a quantum internet, connecting quantum computers and capable of highly secure data transmission, is enticing, but making it poses a formidable challenge. Transporting quantum information requires working with individual photons rather than the light sources used in conventional fiber optic networks. To produce and manipulate individual photons, scientists are turning to quantum light emitters, also known as color centers. These atomic-scale defects in semiconductor materials can emit single photons of fixed wavelength or color and allow photons to interact with electron spin properties in controlled ways.

A team ...

Scientists create 3D models of freshwater mussels to help save them from extinction

2023-08-22

Scientists and imaging specialists have teamed up to help save one of the world’s most endangered groups of animals: freshwater mussels. With funding provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Conservation Training Center, imaging experts will create 3D shell models based on specimens from the Florida Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History.

Once complete, the models will be available online for free to educate the public about these amazing yet little-known creatures that ...

How bacteria surf cargo through the cell

2023-08-22

Bacteria live in nearly every habitat on earth including within soil, water, acidic hot springs and even within our own guts.

Many are involved in fundamental processes like fermentation, decomposition and nitrogen fixation. But scientists don’t understand a fundamental process within bacteria cells: how they organize themselves before division.

Driving vs. surfing

When cells divide the cell splits into two “daughter cells” with the same genetic material as the original cell.

During this process, the DNA and other cellular components replicate, and then this “cargo” ...

JMIR Nursing Call for Papers Theme Issue on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Nursing

2023-08-22

JMIR Nursing Editor-in-Chief: Elizabeth Borycki RN, PhD, FIAHIS, FACMI, FCAHS and theme editor Kenrick Dwain Cato, PhD, RN, CPHIMS, FAAN welcome submissions to a special theme issue examining "Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Nursing."

AI is revolutionizing health care. Nurse informaticist developers, researchers, practitioners, clinicians, educators, and innovators have designed, developed, implemented, and used AI to support patients, their families, nurses and health care activities.

AI has been used to support ...

New study sheds light on the molecular mechanisms underlying SLC29A3 disorders

2023-08-22

In humans, the SLC29A3 gene regulates the function of lysosomes to control waste recycling in cells such as macrophages (that engulf and destroy foreign bodies). This gene encodes for the lysosomal protein that transport nucleosides — degradation products of RNA and DNA — from lysosomes to the cytoplasm. Loss-of-function mutations in the SLC29A3 gene lead to aberrant nucleoside storage, resulting in a spectrum of conditions called SLC29A3 disorders. These disorders can manifest in the form of pigmented skin patches, enlargement of the liver/spleen, hearing loss, or type 1 diabetes. A key manifestation of this group of disorders is histiocytosis, ...

MPFI's Wang Lab awarded $1 million grant to study mechanism behind memory decline in Alzheimer’s

2023-08-22

Max Planck Florida will be able to expand their research program to investigate the neural circuits underlying Alzheimer’s disease with new support. The National Institute on Aging of the NIH has awarded Dr. Yingxue Wang $1,038,819 over three years as part of the Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative Fund. The research will shed new light on how the brain forms new memories and maintains them over time and what can lead to memory decline during Alzheimer’s Disease.

Turning our daily experiences ...

USPSTF recommendation on preexposure prophylaxis to prevent acquisition of HIV

2023-08-22

Bottom Line: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that clinicians prescribe preexposure prophylaxis using effective antiretroviral therapy to persons at increased risk of HIV acquisition to decrease the risk of acquiring HIV. An estimated 1.2 million persons in the U.S. currently have HIV, and more than 760,000 persons have died of complications related to HIV since the first cases were reported in 1981. Although treatable, HIV is not curable and has significant health consequences. Therefore, effective strategies to prevent HIV are an important public health and ...

This fish doesn't just see with its eyes -- it also sees with its skin.

2023-08-22

DURHAM, N.C. -- A few years ago while on a fishing trip in the Florida Keys, biologist Lori Schweikert came face to face with an unusual quick-change act. She reeled in a pointy-snouted reef fish called a hogfish and threw it onboard. But later when she went to put it in a cooler she noticed something odd: its skin had taken on the same color and pattern as the deck of the boat.

A common fish in the western Atlantic Ocean from North Carolina to Brazil, the hogfish is known for its color-changing skin. ...

New antibiotic from microbial ‘dark matter’ could be powerful weapon against superbugs

2023-08-22

A new powerful antibiotic, isolated from bacteria that could not be studied before, seems capable to combat harmful bacteria and even multi-resistant ‘superbugs’. Named Clovibactin, the antibiotic appears to kill bacteria in an unusual way, making it more difficult for bacteria to develop any resistance against it. Researchers from Utrecht University, Bonn University (Germany), the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF), Northeastern University of Boston (USA), and the company NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, USA) now share the discovery of Clovibactin and its killing mechanism in the scientific journal Cell.

Urgent need for new antibiotics

Antimicrobial ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

[Press-News.org] Researchers decode new antibioticCooperation between the University of Bonn, the USA and the Netherlands cracks the mode of action of clovibactin