(Press-News.org) Aug. 28, 2023

Images

ANN ARBOR—University of Michigan researchers have discovered that the same cellular mechanism involved in a form of cystic fibrosis is also implicated in a form of a rare disease called cystinosis.

The mechanism cleans up mutated proteins. In cystinosis, a genetic disease, this allows cystine crystals to build up in the cell. This disrupts the cell, and eventually, tissues and ultimately organs, particularly the kidneys and the eyes.

The problem begins when the lysosome, an organelle within the cell, is unable to do its job. Often called the recycling center of the cell, the lysosome takes in cellular garbage, breaks it down into reusable cellular building blocks, then transports those materials back into the cell.

But when the protein that transports one of the recycled amino acids back into the cell mutates and fails, a cellular mechanism cleans up the faulty protein, allowing amino acid, or cystine, to build up in the lysosome.

"If cystinosis not treated at an early age, some of the effects are irreversible and it could include impaired growth, kidney failure and neurological problems," said Varsha Venkatarangan, graduate student in the U-M Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology and lead author of the study. "Typically, the symptoms of the disease are treated rather than the root problem. So we have been wondering what could be the possible cellular mechanism of this disease."

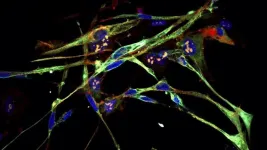

Venkatarangan worked with fibroblasts, skin tissue cells derived from patients with the disease. Using these cells, she determined that this disease mechanism called endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation, or ERAD, degrades a mutated version of the lysosome cystine transporter.

ERAD is the same mechanism behind other diseases such as a major form of cystic fibrosis. And because this mechanism has been identified, the researchers were able to show that previously identified drug molecules were able to help the transporter protein remain stable. Their findings are now published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"This drug molecule is a small chemical that can somehow assist the protein folding of the mutant and protect it from being degraded," said MCDB professor Ming Li. "This chemical chaperone helps it achieve the right formation so that it can be functional."

The lab, led by Li, became interested in the cystine transporting protein and wanted to understand how mutations in the transporter gene caused cystinosis. They painstakingly collected nearly 40 mutations that caused cystinosis and studied their protein stability. The researchers identified one striking mutation that had a very short half life compared to the non-mutated form of the protein.

"We were interested about the fact that this disease mutant was degrading so rapidly, what was the potential mechanism by which it was degrading, and the machinery involved," Venkatarangan said.

So Venkatarangan performed numerous genetic and chemical tests to inhibit different protein degradation machinery of the cell, narrowing down which cellular mechanism was involved in the disease. She determined that the mechanism was ERAD, a cellular pathway located in the cell's endoplasmic reticulum. The cell's endoplasmic reticulum is a network of tiny tubes and sheets that help ferry the cell's proteins to their destination. ERAD targets misfolded proteins and marks them for protein degradation.

And because this is a commonly known disease mechanism, involved in cystic fibrosis, drug molecules had already been identified to work around the ERAD mechanism and prolong the life of the protein. These drug molecules, Li said, are called chemical chaperones and help the protein achieve the right formation so that they can be functional.

"This small chemical chaperone can somehow magically—we don't know the exact mechanism—bind to our mutant and protect the protein from being degraded," Li said.

The researchers were able to stabilize the protein and determine that it was in the right location where it could function to ferry amino acids out of the lysosome, but they then needed to determine whether the transporter was still functional. Performing an assay in collaboration with UCSD, the researchers measured the cystine concentration in the lysosome. With a functional transporter, the lysosome would have lower amounts of amino acid.

"The reduction was pretty dramatic—nearly a 70% reduction of the accumulation level," Li said. "That directly brought the system level to almost normal. If we actually used this chemical chaperone to treat patients, it's possible that we could directly bring down the cystine accumulation in the lysosome."

People may wonder why a disease mechanism found in the endoplasmic reticulum might affect the function of lysosome membrane proteins, Li said. That's because lysosome membrane proteins are transported from the endoplasmic reticulum.

While the lysosome is being built, it needs a lot of trafficking proteins. These lysosomal proteins go through the endoplasmic reticulum and then the Golgi apparatus, which packages the proteins and sends them to the lysosome. During protein trafficking, they have to fold properly. Otherwise, they will be degraded prematurely by protein quality control systems such as ERAD.

These mutant proteins disappear early in the trafficking stage, the researchers discovered, after getting stuck and degraded in the endoplasmic reticulum.

In finding a new purpose for a drug already in use, the team also fulfilled a goal of a program at the National Institutes of Health that encourages finding new uses for already-approved drugs as this leads to faster therapies. However, the team emphasizes that the work is preliminary, done only in cultured patient cells, and the drug has not been tested to treat cystinosis in animals or humans.

"Again, this is preliminary work that was done in patient cells, so we don't really know the systemic effect or how well it works in actual patients," Venkatarangan said. "Our finding also emphasizes the importance of precision medicine, because most of the time, disease mutations are treated similarly under one umbrella of a particular disease.

"But the fact that individual mutations may actually have their own pathogenesis mechanism emphasizes that understanding the individual patient mechanism might help them with a better treatment strategy."

Co-authors of the paper include U-M MCDB's Weichao Zhang and Xi Yang. Jess Thoene of the Department of Pediatrics at the U-M Medical School and Si Houn Hahn of the Seattle Children's Hospital at University of Washington School of Medicine also contributed to the study.

END

Rare disease shares mechanism with cystic fibrosis

2023-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Once rhabdomyosarcoma, now muscle

2023-08-28

“Every successful medicine has its origin story. And research like this is the soil from which new drugs are born,” says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Christopher Vakoc.

For six years, Vakoc’s lab has been on a mission to transform sarcoma cells into regularly functioning tissue cells. Sarcomas are cancers that form in connective tissues like muscle. Treatment often involves chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation—procedures that are especially tough on kids. If doctors could transform cancer cells into healthy cells, it would offer patients a whole new treatment option—one that could spare them and their families a great deal of ...

Past abrupt changes in North Atlantic Overturning have impacted the climate system across the globe

2023-08-28

The Dansgaard-Oeschger events are rapid Northern-Hemisphere temperature jumps of up to 15°C in Greenland that repeatedly occurred within a few decades during the last ice age. “These events are the archetype of abrupt climate changes and further increasing our understanding of them is crucial for more reliable assessments of the risk and possible impacts of future large-scale climate tipping events”, says Niklas Boers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and the Technical University of Munich, one of the authors of the study to be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences PNAS.

In the ...

Historic red tide event of 2020 fueled by plankton super swimmers

2023-08-28

A major red tide event occurred in waters off Southern California in the spring of 2020, resulting in dazzling displays of bioluminescence along the coast. The spectacle was caused by exceedingly high densities of Lingulodinium polyedra (L. polyedra), a plankton species renowned for its ability to emit a neon blue glow. While the red tide captured the public’s attention and made global headlines, the event was also a harmful algal bloom. Toxins were detected at the height of the bloom that had the potential to harm marine life, and dissolved oxygen levels dropped to near-zero as the extreme biomass of the red tide decomposed. This lack of oxygen led to fish die-offs ...

Intravascular imaging associated with improved outcomes compared with angiography

2023-08-28

Amsterdam, Netherlands – 27 Aug 2023: Intravascular imaging-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with a lower rate of target lesion failure compared with angiography-guided PCI, according to late breaking research presented in a Hot Line session today at ESC Congress 2023.1

Numerous randomised trials have compared intravascular imaging-guided PCI with angiography-guided PCI. However, most of these prior trials have used intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Optical coherence ...

Pulsed field ablation is noninferior to thermal ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

2023-08-28

Amsterdam, Netherlands – 27 Aug 2023: Pulsed field ablation (PFA) is as effective and safe as conventional thermal ablation for the treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), according to late breaking research presented in a Hot Line session today at ESC Congress 2023.1

ESC guidelines recommend catheter ablation after failure of drug therapy in patients with paroxysmal AF.2 Conventional ablation technology uses thermal energy (either heat/radiofrequency energy or cold/cryothermal energy) to ablate the tissue. Unlike thermal ablation, PFA uses high energy electrical pulses to destroy tissue by a process called electroporation. Preclinical ...

Mazin to study ab initio engineering of doped-covalent-bond superconductors

2023-08-28

Mazin To Study Ab Initio Engineering Of Doped-Covalent-Bond Superconductors

Igor Mazin, Professor of Practice for Advanced Studies in Theoretical Physics, Quantum Materials Center, Physics and Astronomy, is set to receive funding for the project: "Collaborative research: Ab Initio Engineering of Doped-Covalent-Bond Superconductors."

This EAGER award will support a joint computational and theoretical effort to guide the search for practical superconducting materials.

Superconductors carry electrical current without any resistance when cooled down below a certain material-dependent ...

Marasco bridging chemistry & AI-empowered imaging for secure & trustworthy human identity verification

2023-08-28

Marasco Bridging Chemistry & AI-Empowered Imaging For Secure & Trustworthy Human Identity Verification

Emanuela Marasco, Assistant Professor, Center for Secure Information Systems, received funding for the project: "EAGER: SaTC: Sweaty Digits: Bridging Chemistry and AI-Empowered Imaging for Secure and Trustworthy Human Identity Verification."

Marasco seeks to characterize a person's extrinsic and intrinsic features for a more accurate representation of their identity by exploiting selected compounds ...

COS researchers transitioning training dataset labeling tool to support discoveries in earth science & heliophysics

2023-08-28

COS Researchers Transitioning Training Dataset Labeling Tool To Support Discoveries In Earth Science & Heliophysics

Chaowei Yang, Professor, Director, NSF Spatiotemporal Innovation Center, Geography and Geoinformation Science, and Jie Zhang, Professor, Physics and Astronomy, received funding for the project: "Transitioning a Training Dataset Labeling Tool (TDLT) to Support Discoveries in Earth Science and Heliophysics."

The researchers are creating a generalizable training dataset labeling tool for both Earth and heliophysics by ...

Still separate and unequal: How subsidized housing exacerbates inequality

2023-08-28

For years, scholars, advocates and journalists have highlighted the ongoing racism and segregation in the housing market, yet a segment of the housing market — government-subsidized housing — has been overlooked, until now.

A new study from researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and other institutions is the first in decades to investigate racial inequality in the subsidized housing market. Using restricted 2017 American Housing Survey data provided by the U.S. Department ...

Ambulances should take cardiac arrest victims to closest emergency department

2023-08-28

Amsterdam, Netherlands – 27 Aug 2023: A randomised trial involving all hospitals in London, UK, has found no difference in survival at 30 days in patients with resuscitated cardiac arrest in the community who were taken by ambulance to a cardiac arrest centre compared with those delivered to the geographically closest emergency department. That’s the finding of late breaking research presented in a Hot Line session today at ESC Congress 2023.1 The study also found no overall difference in neurological outcomes at discharge and at three months between groups.

Sudden ...