(Press-News.org) The rotating shoulders and extending elbows that allow humans to reach for a high shelf or toss a ball with friends may have first evolved as a natural braking system for our primate ancestors who simply needed to get out of trees without dying.

Dartmouth researchers report in the journal Royal Society Open Science that apes and early humans likely evolved free-moving shoulders and flexible elbows to slow their descent from trees as gravity pulled on their heavier bodies. When early humans left forests for the grassy savanna, the researchers say, their versatile appendages were essential for gathering food and deploying tools for hunting and defense.

The researchers used sports-analysis and statistical software to compare videos and still-frames they took of chimpanzees and small monkeys called mangabeys climbing in the wild. They found that chimps and mangabeys scaled trees similarly, with shoulders and elbows mostly bent close to the body. When climbing down, however, chimpanzees extended their arms above their heads to hold onto branches like a person going down a ladder as their greater weight pulled them downward rump-first.

Luke Fannin, first author of the study and a graduate student in Dartmouth's Ecology, Evolution, Environment and Society program, said the findings are among the first to identify the significance of "downclimbing" in the evolution of apes and early humans, which are more genetically related to each other than to monkeys. Existing research has observed chimps ascending and navigating trees—usually in experimental setups—but the researchers' extensive video from the wild allowed them to examine how the animals' bodies adapted to climbing down, Fannin said.

"Our study broaches the idea of downclimbing as an undervalued, yet incredibly important factor in the diverging anatomical differences between monkeys and apes that would eventually manifest in humans," Fannin said. "Downclimbing represented such a significant physical challenge given the size of apes and early humans that their morphology would have responded through natural selection because of the risk of falls."

"Our field has thought about apes climbing up trees for a long time—what was essentially absent from the literature was any focus on them getting out of a tree. We've been ignoring the second half of this behavior," said study co-author Jeremy DeSilva, professor and chair of anthropology at Dartmouth.

"The first apes evolved 20 million years ago in the kind of dispersed forests where they would go up a tree to get their food, then come back down to move on to the next tree," DeSilva said.

"Getting out of a tree presents all kinds of new challenges. Big apes can't afford to fall because it could kill or badly injure them. Natural selection would have favored those anatomies that allowed them to descend safely."

Flexible shoulders and elbows passed on from ancestral apes would have allowed early humans such as Australopithecus to climb trees at night for safety and come down in the daylight unscathed, DeSilva said. Once Homo erectus could use fire to protect itself from nocturnal predators, the human form took on broader shoulders capable of a 90-degree angle that—combined with free-moving shoulders and elbows—made our ancestors excellent shots with a spear (apes cannot throw accurately).

"It’s that same early-ape anatomy with a couple of tweaks. Now you have something that can throw a spear or rocks to protect itself from being eaten or to kill things to eat for itself. That's what evolution does—it's a great tinkerer," DeSilva said.

"Climbing down out of a tree set the anatomical stage for something that evolved millions of years later," he said. "When an NFL quarterback throws a football, that movement is all thanks to our ape ancestors."

Despite chimps' lack of grace, Fannin said, their arms have adapted to ensure the animals reach the ground safely—and their limbs are remarkably similar to those of modern humans.

"It's the template that we came from—going down was probably far more of a challenge for our early ancestors, too," Fannin said. "Even once humans became upright, the ability to ascend, then descend, a tree would've been incredibly useful for safety and nourishment, which is the name of the game when it comes to survival. We're modified, but the hallmarks of our ape ancestry remain in our modern skeletons."

The researchers also studied the anatomical structure of chimp and mangabey arms using skeletal collections at Harvard University and The Ohio State University, respectively. Like people, chimps have a shallow ball-and-socket shoulder that—while more easily dislocated—allows for a greater range of movement, Fannin said. And like humans, chimps can fully extend their arms thanks to the reduced length of the bone just behind the elbow known as the olecranon process.

Mangabeys and other monkeys are built more like quadrupedal animals such as cats and dogs, with deep pear-shaped shoulder sockets and elbows with a protruding olecranon process that make the joint resemble the letter L. While these joints are more stable, they have a much more limited flexibility and range of movement.

The researchers' analysis showed that the angle of a chimp's shoulders was 14 degrees greater during descent than when climbing up. And their arm extended outward at the elbow 34 degrees more when coming down from a tree than going up. The angles at which mangabeys positioned their shoulders and elbows were only marginally different—4 degrees or less—when they were ascending a tree versus downclimbing.

"If cats could talk, they would tell you that climbing down is trickier than climbing up and many human rock climbers would agree. But the question is why is it so hard," said study co-author Nathaniel Dominy, the Charles Hansen Professor of Anthropology and Fannin's adviser.

"The reason is that you're not only resisting the pull of gravity, but you also have to decelerate," Dominy said. "Our study is important for tackling a theoretical problem with formal measurements of how wild primates climb up and down. We found important differences between monkeys and chimpanzees that may explain why the shoulders and elbows of apes evolved greater flexibility."

Co-author Mary Joy, who led the study with Fannin for her undergraduate thesis and graduated from Dartmouth in 2021, was reviewing videos of chimps that DeSilva had filmed when she noticed the difference in how the animals descended trees than how they went up them.

"It was very erratic, just crashing down, everything's flying. It's very much a controlled fall," Joy said. "In the end, we concluded that the way chimps descend a tree is likely related to weight. Greater momentum potentially expends less energy and they're much more likely to reach the ground safely than by making small, restricted movements."

But as a trail runner, Joy knew the pained feeling of inching down an incline in short clips instead of just hurtling down the path with the pull of gravity, her legs extended forward to catch her at the end of each stride.

"When I'm moving downhill, the slower I'm going and restricting my movement, the more I'm fatiguing. It catches up to me very quickly. No one would think the speed and abandon with which chimps climb down from trees would be the preferred method for a heavier primate, but my experience tells me it's more energy efficient," she said.

"Movement in humans is a masterpiece of evolutionary compromises," Joy said. "This increased range of motion that began in apes ended up being pretty good for us. What would the advantage of losing that be? If evolution selected for people with less range of motion, what advantages would that confer? I can't see any advantage to losing that."

The paper, "Downclimbing and the evolution of ape forelimb morphologies," was published Sept. 6 by Royal Society Open Science. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS 0840110, 0921770, 0922429, GRFP 1840344), the Clare Garber Goodman Fund and the James O. Freedman Presidential Scholars Research Fund at Dartmouth, a Mamont Scholars Grant from The Explorers Club, the Leakey Foundation, and the Primate Society of Great Britain.

###

END

Human shoulders and elbows first evolved as brakes for climbing apes

Study introduces 'downclimbing' from trees as a driver in early-human evolution

2023-09-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

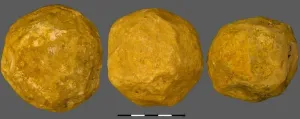

The limestone spheroids of ‘Ubeidiya: Intentional imposition of symmetric geometry by early hominins?

2023-09-06

Limestone spheroids, enigmatic lithic artifacts from the ancient past, have perplexed archaeologists for years. While they span from the Oldowan to the Middle Palaeolithic, the purpose behind their creation remains a subject of intense debate. Now, a study conducted by a team from the Computational Archaeology Laboratory of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in collaboration with researchers from Tel Hai College and Rovira i Virgili University seeks to shed light on these mysterious objects, offering insights into the intentions and skills of early hominins.

Spheroids ...

Balancing biodiversity, climate change, food for a trifecta

2023-09-06

Across the globe, and particularly in Brazil, lies an embarrassment of riches that also stage a showdown as mitigating climate change and protecting biodiversity square off against growing food.

In this week’s Science of the Total Environment, scientists from and once affiliated with Michigan State University’s Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (MSU-CSIS) identify ways for landowners in rural areas to be able to capitalize on win-win situations, whether they have fruitful land ...

COVID-19 vaccination appears safe in study of patients with glomerular diseases

2023-09-05

Among 2,055 adults with a wide range of glomerular diseases, the COVID-19 vaccination did not adversely affect kidney function or worsen kidney damage and appeared safe in this population.

Patients with glomerular disease (GN) may be at increased risk of severe COVID-19, yet concerns over vaccines causing disease relapse may lead to vaccine hesitancy. Researchers examined the associations of COVID-19 with longitudinal kidney function and proteinuria and compared these to similar associations with COVID-19 vaccination. In this cohort study of 2,055 patients with minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy, or ...

Study: Health equity an important aspect of improving quality of care provided to children in emergency departments

2023-09-05

INDIANAPOLIS—A new multi-site study led by Indiana University School of Medicine found increasing pediatric readiness in emergency departments reduces, but does not eliminate, racial and ethnic disparities in children and adolescents with acute medical emergencies.

The study also involved researchers from Oregon Health and Science University and UC Davis Health. They recently published their findings in JAMA Open Network.

“Ours is a national study group focused on pediatric emergency department readiness,” said Peter Jenkins, MD, associate professor surgery at IU School of Medicine and first ...

UMass Amherst researcher shines light on effectiveness of school sunscreen legislation

2023-09-05

AMHERST, Mass. – States that enacted laws permitting children to carry and apply sunscreen at school experienced an increased interest in sun protection and a higher rate of sunscreen use among adolescents, according to new research by a University of Massachusetts Amherst resource economist.

Brandyn Churchill, assistant professor of resource economics at UMass Amherst, is co-author of the study that is the first to examine state-level “SUNucate” laws, which permit students to apply sunscreen at school and wear sun-protective clothing even if it does not ...

Fossil spines reveal deep sea’s past

2023-09-05

Right at the bottom of the deep sea, the first very simple forms of life on earth probably emerged a long time ago. Today, the deep sea is known for its bizarre fauna. Intensive research is being conducted into how the number of species living on the sea floor have changed in the meantime. Some theories say that the ecosystems of the deep sea have emerged again and again after multiple mass extinctions and oceanic upheavals. Today's life in the deep sea would thus be comparatively young in the history of the Earth. But there is increasing evidence that parts of this world are much older than previously thought. A research team led by the University ...

MSU researchers discover link between cholesterol and diabetic retinopathy

2023-09-05

Images

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Advancements that could lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment for diabetic retinopathy, a common complication that affects the eyes, have been identified by a multi-department research team from Michigan State and other universities.

Their findings were recently published in Diabetologia, the official journal of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Additional contributors are from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Case Western Reserve University and Western University ...

New model helps FAMU-FSU researchers locate best spots for field hospitals after disasters

2023-09-05

FAMU-FSU College of Engineering researchers want Floridians to be prepared when the next pandemic or hurricane hits the state. A new study published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction examines the best locations for field hospitals that can supplement health care facilities when resources are stretched thin.

“One of the goals of RIDER is to look after our most vulnerable when disasters hit,” said Eren Ozguven, director of the Resilient Infrastructure ...

OHSU scientists discover new cause of Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia

2023-09-05

Researchers have discovered a new avenue of cell death in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

A new study, led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University and published online in the journal Annals of Neurology on Aug. 21, reveals for the first time that a form of cell death known as ferroptosis — caused by a buildup of iron in cells — destroys microglia cells, a type of cell involved in the brain’s immune response, in cases of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

The ...

JNM publishes consensus statement on patient selection and appropriate use of Lu-177 PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy

2023-09-05

Reston, VA—The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) has issued a new consensus statement to provide standardized guidance for the selection and management of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients being treated with 177Lu-PSMA radionuclide therapy. The statement, published in the July issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine, also reviews current clinical struggles physicians face during treatment with 177Lu-PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 177Lu-PSMA-617 for the treatment of men with mCRPC after progressing on taxane-based chemotherapy ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

[Press-News.org] Human shoulders and elbows first evolved as brakes for climbing apesStudy introduces 'downclimbing' from trees as a driver in early-human evolution