(Press-News.org) If you happen to come across plants of the Balanophoraceae family in a corner of a forest, you might easily mistake them for fungi growing around tree roots. Their mushroom-like structures are actually inflorescences, composed of minute flowers.

But unlike some other parasitic plants that extend an haustorium into host tissue to steal nutrients, Balanophora induces the vascular system of their host plant to grow into a tuber, forming a unique underground organ with mixed host-parasite tissue. This chimeric tuber is the interface where Balanophora steals nutrients from its host plant.

But how these subtropical extreme parasitic plants evolved into their current form piqued the interest of Dr. Xiaoli Chen, a scientist with BGI Research and lead author of a new study published this week in Nature Plants.

Dr. Chen and colleagues—including University of British Columbia botanist Dr. Sean Graham—compared the genomes of Balanophora and Sapria, another extreme parasitic plant in the family Rafflesiaceae that has a very different vegetative body.

The study revealed Sapria and Balanophora have lost 38 per cent and 28 per cent of their genomes respectively, while evolving to become holoparasitic—record shrinkages for flowering plants.

“The extent of similar, but independent gene losses observed in Balanophora and Sapria is striking,” said Dr. Chen. “It points to a very strong convergence in the genetic evolution of holoparasitic lineages, despite their outwardly distinct life histories and appearances, and despite their having evolved from different groups of photosynthetic plants.”

The researchers found a near-total loss of genes associated with photosynthesis in both Balanophora and Sapria, as would be expected with the loss of photosynthestic capability.

But the study also revealed a loss of genes involved in other key biological processes—root development, nitrogen absorption, and regulation of flowering development. The parasites have shed or compacted a large fraction of the gene families normally found in green plants—the large sets of duplicated gene plants that tend to perform related biological functions. This supports the idea that the parasites retain only those genes or gene copies that are essential.

Most astonishingly, genes related to the synthesis of a major plant hormone, abscisic acid (ABA), which is responsible for plant stress responses and signaling, have been lost in parallel in Balanophora and Sapria. Despite this, the researchers still recorded accumulation of the ABA hormone in flowering stems of Balanophora, and found that genes involved in the response to ABA signaling are still retained in the parasites.

"The majority of the lost genes in Balanophora are probably related to functions essential in green plants, which have become functionally unnecessary in the parasites,” said Dr. Graham.

“That said, there are probably instances where the gene loss was actually beneficial, rather than reflecting a simply loss of function. The loss of their entire ABA biosynthesis pathway may be a good example. It may help them to maintain physiological synchronization with the host plants. This needs to be tested in the future."

Dr. Huan Liu, a researcher at BGI Research, emphasized the significance of the study in the context of 10KP—a project to sequence the genomes of 10,000 plant species.

"The study of parasitic plants deepens our understanding of dramatic genomic alterations and the complex interactions between parasitic plants and their hosts. The genomic data provides valuable insights into the evolution and genetic mechanisms behind the dependency of parasitic plants on their hosts, and how they manipulate host plants to survive."

END

This parasitic plant convinces hosts to grow into its own flesh—it’s also an extreme example of genome shrinkage

2023-09-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mutations in 11 genes associated with aggressive prostate cancer identified in new research

2023-09-21

An international research team led by scientists in the Center for Genetic Epidemiology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center has singled out mutations in 11 genes that are associated with aggressive forms of prostate cancer. These findings come from the largest-scale prostate cancer study ever exploring the exome — that is, the key sections of the genetic code that contain the instructions to make proteins. The scientists analyzed samples from about 17,500 prostate cancer ...

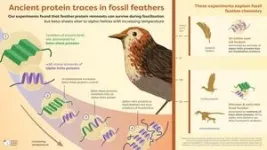

Dinosaur feathers reveal traces of ancient proteins

2023-09-21

Palaeontologists at University College Cork (UCC) in Ireland have discovered X-ray evidence of proteins in fossil feathers that sheds new light on feather evolution.

Previous studies suggested that ancient feathers had a different composition to the feathers of birds today. The new research, however, reveals that the protein composition of modern-day feathers was also present in the feathers of dinosaurs and early birds, confirming that the chemistry of feathers originated much earlier than previously thought.

The research, published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution, was led by palaeontologists ...

Researchers develop first method to study microRNA activity in single cells

2023-09-21

MicroRNAs are small molecules that regulate gene activity by binding to and destroying RNAs produced by the genes. More than 60% of all human genes are estimated to be regulated by microRNAs, therefore it is not surprising that these small molecules are involved in many biological processes including diseases such as cancer. To discover the function of a microRNA, it is necessary to find out exactly which RNAs are targeted by it. While such methods exist, they require a lot of material typically in order of millions of cells, to ...

Nanoparticles made from plant viruses could be farmers’ new ally in pest control

2023-09-21

A new form of agricultural pest control could one day take root—one that treats crop infestations deep under the ground in a targeted manner with less pesticide.

Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed nanoparticles, fashioned from plant viruses, that can deliver pesticide molecules to soil depths that were previously unreachable. This advance could potentially help farmers effectively combat parasitic nematodes that plague the root zones of crops, all while minimizing costs, pesticide use and environmental toxicity.

Controlling infestations caused by root-damaging nematodes has long been a challenge in agriculture. One reason is that the types of pesticides ...

Social vs. language role: researchers question function of two brain areas

2023-09-21

A research team led by Prof. LIN Nan from the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences found that during sentence processing, the neural activity of two canonical language areas, i.e., the left ventral temporoparietal junction (vTPJ) and the lateral anterior temporal lobe (lATL), is associated with social-semantic working memory rather than language processing per se.

The study was published in Nature Human Behaviour on Sept. 21.

Language and social cognition are two deeply interrelated abilities of the human species, but have traditionally been studied ...

Inauguration ceremony of carbon future

2023-09-21

On September 17th, 2023, Carbon Future, an international interdisciplinary journal sponsored by Tsinghua University, has been officially inaugurated.

Carbon Future is an open access, peer-reviewed and international interdisciplinary journal that reports carbon-related materials and processes, including carbon materials, catalysis, energy conversion and storage, as well as low carbon emission process and engineering. The journal is published quarterly by Tsinghua University Press, and publicly released on SciOpen, an internationally digital ...

Revolutionizing data storage: DNA movable-type system paves the way for sustainable data storage technology

2023-09-21

In a groundbreaking study published in Engineering, researchers have developed a revolutionary method for data storage using DNA. The paper titled “Engineering DNA Materials for Sustainable Data Storage Using a DNA Movable-Type System” introduces a novel approach that utilizes DNA fragments, referred to as “DNA movable types,” for data writing, thereby eliminating the need for costly and environmentally hazardous DNA synthesis.

DNA molecules have long been recognized as green materials ...

NIH center grant bolsters male contraceptive research

2023-09-21

Weill Cornell Medicine has received a three-year, nearly $6 million grant to lead one of three national contraceptive research centers. The grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, part of the National Institutes of Health, will fund the Weill Cornell Medicine Contraception Development Research Center. Led by Drs. Jochen Buck and Lonny Levin, both professors of pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine, the center will focus on developing an on-demand male contraceptive.

“It’s an honor to be selected for a second time for this award,” Dr. Levin ...

Supportive later-life social relationships mediate the risk of severe frailty in adults who had negative childhood experiences

2023-09-21

INDIANAPOLIS -- Frailty is a serious concern in later-life adults due to its association with additional health risks including disability, falls, hospitalization and mortality. The prevalence of frailty has risen over time; about 15 percent of those aged 65 years and older are considered frail.

In one of the first studies to analyze the mediating effects of social relationships in the relationship between childhood experiences and frailty, Regenstrief Research Scientist Monica M. Williams-Farrelly, PhD, has found ...

Towards a better understanding of early human embryonic development

2023-09-21

The onset of embryo-specific gene transcription, also known as embryonic genome activation (EGA), is a crucial step in the developmental journey of an organism. Although EGA has been studied to some extent in mice, human EGA remains largely unexplored, mainly due to the lack of novel in vitro cell models and ethical restrictions on the usage of human embryos. Thus, cell models resembling the human blastomere stage—when the embryo undergoes a cell duplication process—are necessary to study the earliest stages of human EGA and understand the events that occur during early embryonic development.

To ...