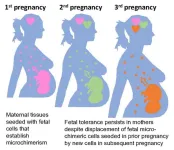

(Press-News.org) Scientists have known for decades that pregnancy requires a mother’s body to adjust so that her immune system does not attack the growing fetus as if it were a hostile foreign invader. Yet despite learning a great deal more about the immunology of pregnancy in recent years, a new study shows that the cellular crosstalk between a mother and her offspring is even more complex and long-lasting than expected.

The study was published online Sept. 21, 2023, in the journal Science by a research team led by Sing Sing Way, MD, PhD, Division of Infectious Diseases at Cincinnati Children’s and the Center for Inflammation and Tolerance.

“By investigating how prior pregnancy changes the outcomes of future pregnancies--or in other words how mothers remember their babies--our findings add a new dimension to our understanding of how pregnancy works,” Way says. “Nature has designed built-in resiliency in mothers that generally reduces the risk of preterm birth, preeclampsia, and stillbirth in women who have a prior healthy pregnancy. If we can learn ways to mimic these strategies, we may be better able to prevent complications in high-risk pregnancies.”

In addition to potentially making progress against the leading cause of infant mortality, Way says understanding how the immune system changes during pregnancy could influence other research fields including vaccine development, autoimmunity research, and how to prevent organ transplant rejection.

How Moms Remember Their Babies

In 2012, Way and colleagues published a study in Nature that revealed how the experience of a first pregnancy makes a woman’s body much less likely to reject a second pregnancy with the same father.

In addition to previously known short-term immune system adjustments, the researchers found that the mother’s body keeps a longer-term supply of immune suppressive T cells that specifically recognize the next fetus by the same couple. These suppressive T cells instruct the rest of the immune system to stand down as the pregnancy develops and linger in the mother’s body for years after giving birth.

For immunity against infection, such “memory” cells often require a constant, low level of exposure to the invading pathogen. So, initially, scientists were surprised to find these suppressive cells persisting in mothers well beyond childbirth.

The new study in Science reports that maintaining protective memory suppressive T cells is mediated by tiny populations of baby cells that remain in mothers after pregnancy called fetal microchimeric cells. This finding provides further biological evidence to support a widely recognized special connection between mothers and their children.

“Very small numbers of fetal cells can be found in the heart, liver, intestine, uterus and other tissues,” Way says. “The fact that we are made up of more than just cells with our own genetics, but also cells from our mothers and our children is a fascinating idea.”

This influence linked to fetal cells builds on research Way and colleagues published in Cell in 2015 that shows children maintain a small supply of cells transferred from their mothers during pregnancy called maternal microchimeric cells. Even many years later, these cells help explain why an organ transplant from a person’s mother is more likely to be successful compared to a donor organ from their father.

But there’s more to the story, Way says.

This potentially wide assortment of genetically foreign cells in women, including maternal microchimeric cells from their mother and unique fetal microchimeric cells from each pregnancy raises fundamental new questions about how microchimeric cells interact with each other, and the limits of their accumulation. The current Science paper shows that each individual can have only one set of microchimeric cells at a time.

Fetal microchimeric cells remaining in mothers from a first pregnancy get displaced by new fetal cells when mothers become pregnant again. Meanwhile, once a grown daughter becomes pregnant, fetal microchimeric cells displace maternal microchimeric cells causing her to immunologically “forget” her mother.

“This transience for individual sets of microchimeric cells is remarkable, especially considering their protective benefits on pregnancy outcomes, and they represent only one in a million cells,” Way says.

However, the new research also shows that mothers never fully forget their children in the same way daughters forget their mothers. While the supply of protective fetal microchimeric cells reflect only the most recent pregnancy, a small number of suppressive T cells from each pregnancy lives on in a latent form within the mother. They can linger for years, until called into action by a new pregnancy.

“This was an unexpected finding,” Way says. “These memory immune cells with latent suppressive properties act as a fail-safe mechanism in addition to the protection from traditional memory suppressive T cells.”

Implications for High-Risk Pregnancy

While the new study is based on studying mouse models, the co-authors say a body of research already exists demonstrating the cellular crosstalk observed in the mice also happens in humans.

One emerging theory that requires further study is that a woman’s immune system may also “remember” bad pregnancy outcomes in much the same way it remembers good outcomes.

“The challenge will be to identify specifically what a mother’s immune system retains from a pregnancy with a poor outcome,” Way says. “If we can isolate how those mechanisms differ from a healthy outcome then we would have a target for developing improved treatments to improve outcomes in high-risk pregnancies.”

Way says it will likely take several years to translate the new study’s findings into possible treatments that could be tested in clinical trials.

Implications for Vaccine Research

While recommended for years by some experts, awareness has grown in recent years that providing vaccines to pregnant woman can protect their newborns from infectious disease threats long before the babies can directly receive their own vaccines.

In June 2022, Way and colleagues detailed in Nature how mothers can produce “super antibodies” that can protect newborns from infectious threats more effectively than previously thought possible. Their findings add weight to recommendations that pregnant women receive all the vaccines available to them.

Just in August, that list of vaccines grew when the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first vaccine that can be given to pregnant women to protect newborns from RSV--the No. 1 cause of lower respiratory tract illness in infants and toddlers. Around the world, some 45,000 children die each year from RSV, including about 300 children a year in the United States. Another 80,000 babies a year in the U.S. get so sick from RSV that they require hospital care.

With new understanding emerging about how the immune system functions during pregnancy, Way predicts that even more vaccines will come along to protect both mother and child.

“We are just beginning to understand how mothers immunologically tolerate their babies during pregnancy. Considering parity or the outcomes of prior pregnancy on the outcomes of future pregnancies add an exciting new dimension for investigating how pregnancy works,” Way says. “On the other hand, given the importance of reproductive fitness in trait selection, immunology learned from mothers and babies can open up new ways to improve vaccines, autoimmunity and transplantation.”

About this study

In addition to Way, co-authors from Cincinnati Children’s included co-first authors Tzu-Yu Shao, PhD, and Jeremy Kinder, PhD; and contributors Gavin Harper, BS, Giang Pham, PhD, Yanyan Peng, PhD, Bryan Sherman, BS, Yuehong Wu, BS, Alexandra Iten, BS, Yueh-Chiang Hu, PhD, Abigail Russi, MD, PhD, John Erickson, MD, PhD, and Hilary Miller-Handley, MD. Co-authors also included University of Cincinnati researchers James Liu, MD, and Emily Gregory, MD.

Funding sources for this study include the National Institutes of Health (DP1AI131080, R01AI120202, R01AI124657); the HHMI Faculty Scholar’s Program; the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; and the March of Dimes Ohio Collaborative.

END

Moms’ ability to ‘remember’ prior pregnancies suggests new strategies for preventing complications

Cincinnati Children’s and University of Cincinnati scientists shed new light on how a woman’s immune system adjusts during and after pregnancy. Implications could extend into vaccine research and organ transplantation.

2023-09-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Curbing violence in Mexico: Disrupting cartel recruitment holds the key, a new study finds

2023-09-21

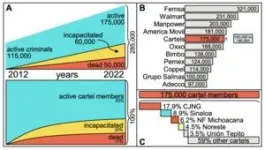

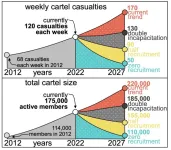

Not through courts and not through prisons. The only way to reduce violence in Mexico is to cut off recruitment. Increasing incapacitation instead leads to both more homicides and cartel members, researcher Rafael Prieto-Curiel from the Complexity Science Hub and colleagues show in a study in Science.

In 2021, approximately 34,000 people died from intentional homicides in Mexico – the equivalent of nearly 27 victims per 100,000 population. This ranks Mexico among the least peaceful countries worldwide.

FIFTH LARGEST EMPLOYER

In order to be able to address this violence ...

Rewiring tumor mitochondria enhances the immune system’s ability to recognize and fight cancer

2023-09-21

Immunotherapy, which uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer, is an effective treatment option, yet many patients do not respond to it. Thus, cancer researchers are seeking new ways to optimize immunotherapy so that it is more effective for more people. Now, Salk Institute scientists have found that manipulating an early step in energy production in mitochondria—the cell’s powerhouses—reduces melanoma tumor growth and enhances the immune response in mice.

The study, published in Science on September 21, ...

Two studies indicate CO2 on Europa’s surface originated from within the moon’s internal ocean

2023-09-21

A pair of independent studies, using recent James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations of carbon dioxide (CO2) ice on Jupiter’s moon Europa, indicate the CO2 originates from a source within the icy body’s subsurface ocean. The findings from both research groups provide new insights into the poorly known composition of Europa’s internal ocean. Beneath a crust of solid water ice, Jupiter’s moon Europa is thought to have a subsurface ocean of salty liquid water. Because of this, Europa is a prime target in the search for life elsewhere in the Solar System. Assessing this deep ...

Global study reveals extensive impact of metal mining contamination on rivers and floodplains, suggesting need for new safeguards to address spike in demand for ‘green’ minerals

2023-09-21

A groundbreaking study, published today in Science, has provided new insights into the extensive impact of metal mining contamination on rivers and floodplains across the world, with an estimated 23 million people believed to be affected by potentially dangerous concentrations of toxic waste.

Led by Professors Mark Macklin and Chris Thomas, Directors of the Lincoln Centre for Water and Planetary Health at the University of Lincoln, UK – working with Dr Amogh Mudbhatkal from the University’s Department of Geography – the study offers a comprehensive understanding of the environmental and health challenges associated with metal mining activities.

Using ...

Regeneration across complete spinal cord injuries reverses paralysis

2023-09-21

When the spinal cords of mice and humans are partially damaged, the initial paralysis is followed by the extensive, spontaneous recovery of motor function. However, after a complete spinal cord injury, this natural repair of the spinal cord doesn’t occur and there is no recovery. Meaningful recovery after severe injuries requires strategies that promote the regeneration of nerve fibers, but the requisite conditions for these strategies to successfully restore motor function have remained elusive.

“Five years ago, we demonstrated that nerve fibers can be regenerated across anatomically complete spinal cord ...

The dance of organ positioning: a tango of three proteins

2023-09-21

In order to keep track of their environment, cells use cilia, antenna-like structures that can sense a variety of stimuli, including the flow of fluids outside the cell. Genetic defects that cause cilia to malfunction and lose their sensory abilities can result in disorders known as “ciliopathies”, including polycystic kidney diseases; but they can also disrupt the correct asymmetric positioning of internal organs during embryonic development – what is known as “organ laterality”.

An example of such asymmetry is the heart, which is typically ...

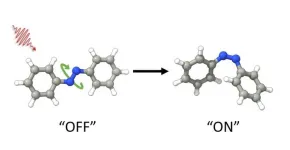

Using harmless light to change azobenzene molecules with new supera molecular complex

2023-09-21

New discovery allows scientists to change the shape of azobenzene molecules using visible light, which is more practical and safe than previously used ultraviolet light. Azobenzenes are incredibly versatile and have many potential uses, such as in making tiny machines and improving technology as well as making light controllable drugs. This molecule can switch between two different forms by light. However, the two forms are in equilibrium, which means that a mixture present that prevents optimal use for applications. Being able to control them with visible light and enrich only one form opens up new possibilities for these applications, making them more efficient ...

Scientists regenerate neurons that restore walking in mice after paralysis from spinal cord injury

2023-09-21

In a new study in mice, a team of researchers from UCLA, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and Harvard University have uncovered a crucial component for restoring functional activity after spinal cord injury. The neuroscientists have shown that re-growing specific neurons back to their natural target regions led to recovery, while random regrowth was not effective.

In a 2018 study published in Nature, the team identified a treatment approach that triggers axons — the tiny fibers that link nerve cells and enable them to communicate — to regrow after spinal cord injury ...

Conversations with plants: Can we provide plants with advance warning of impending dangers?

2023-09-21

Imagine if humans could ‘talk’ to plants and warn them of approaching pest attacks or extreme weather.

A team of plant scientists at the Sainsbury Laboratory Cambridge University (SLCU) would like to turn this science fiction into reality using light-based messaging to ‘talk’ to plants.

Early lab experiments with tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) have demonstrated that they can activate the plant's natural defence mechanism (immune response) using light as a stimulus (messenger).

Light serves as a universal means of daily human communication, for example the signalling at traffic lights, pedestrian ...

Chicago’s West Side is air pollution hotspot

2023-09-21

Three independent state-of-the-art datasets reveal that the West Side has more nitrogen dioxide (NO2) pollution than the rest of the city

Depending on the month, residents in this area experience 16 to 32% higher NO2 concentrations on average

By identifying hotspots, residents and policymakers can be confident about where to prioritize immediate interventions

EVANSTON, Ill. — The western edge of Chicago — including the North and South Lawndale, East Garfield Park, Archer Heights and Brighton Park neighborhoods — experiences up to 32% higher concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) air pollution compared to the rest of the city, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Gibson Oncology, NIH to begin Phase 2 trials of LMP744 for treatment of first-time recurrent glioblastoma

Researchers develop a high-efficiency photocatalyst using iron instead of rare metals

Study finds no evidence of persistent tick-borne infection in people who link chronic illness to ticks

New system tracks blockchain money laundering faster and more accurately

In vitro antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Tithonia diversifolia (asteraceae) and Solanum torvum (solanaceae) against selected shigella species

Qiliang (Andy) Ding, PhD, named recipient of the 2026 ACMG Foundation Rising Scholar Trainee Award

Heat-free gas sensing: LED-driven electronic nose technology enhances multi-gas detection

Women more likely to choose wine from female winemakers

E-waste chemicals are appearing in dolphins and porpoises

Researchers warn: opioids aren’t effective for many acute pain conditions

Largest image of its kind shows hidden chemistry at the heart of the Milky Way

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

People’s gut bacteria worse in areas with higher social deprivation

Unique analysis shows air-con heat relief significantly worsens climate change

Keto diet may restore exercise benefits in people with high blood sugar

Manchester researchers challenge misleading language around plastic waste solutions

Vessel traffic alters behavior, stress and population trends of marine megafauna

Your car’s tire sensors could be used to track you

Research confirms that ocean warming causes an annual decline in fish biomass of up to 19.8%

Local water supply crucial to success of hydrogen initiative in Europe

New blood test score detects hidden alcohol-related liver disease

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

[Press-News.org] Moms’ ability to ‘remember’ prior pregnancies suggests new strategies for preventing complicationsCincinnati Children’s and University of Cincinnati scientists shed new light on how a woman’s immune system adjusts during and after pregnancy. Implications could extend into vaccine research and organ transplantation.