(Press-News.org) When you see a familiar face upright, you’ll recognize it right away. But if you saw that same face upside down, it’s much harder to place. Now researchers who’ve studied Claudio, a 42-year-old man whose head is rotated back almost 180 degrees such that it sits between his shoulder blades, suggest that the reason people are so good at processing upright faces has arisen through a combination of evolution and experience. The findings appear September 22 in the journal iScience.

“Nearly everyone has far more experience with upright faces and ancestors whose reproduction was influenced by their ability to process upright faces, so it's not easy to pull apart the influence of experience and evolved mechanisms tailored for upright faces in typical participants,” says first author Brad Duchaine, a psychologist at Dartmouth College. “However, because Claudio's head orientation is reversed to most faces that he has looked at, he provides an opportunity to examine what happens when the faces viewed most often have a different orientation than the viewer's face.”

Researchers have long known from earlier studies that our ability to process faces drops or even plummets when a face is rotated 180 degrees. But it had been hard to determine if the reason for that comes from evolutionary mechanisms that shaped our brains' facial processing abilities gradually over time or simply because most of us primarily interact with people and see them with their face in an upright position.

The question was: How does Claudio’s altered viewpoint relative to the faces of others change how he is able to detect and match them up? Or does it? The answer, they realized, would offer clues about the nature of face perception in people more generally.

To find out, the researchers tested Claudio’s face-detection and identity-matching ability in 2015 and 2019. They also tested his recognition of Thatcherized faces, in which some of the features, such as the eyes and mouth, had been altered. Across all three types of tests, people with typical face perception are much better at these judgements when faces are upright than when they are inverted.

Their studies found that Claudio was more accurate than controls with inverted detection and Thatcher judgments but scored similarly to controls with face identity matching. The researchers say the findings suggest that our ability with upright faces arises from a combination of evolutionary mechanisms and experience.

“Because Claudio appears to have had more experience with upright faces than upside-down faces and he has viewed faces from an upside-down vantage point, it is revealing that he does not do better with upright faces than inverted faces for face detection and face identity matching,” Duchaine said. “The absence of an advantage for the face orientation that he's had more experience with suggests that our great sensitivity to upright faces results from both our greater experience with them and an evolved component that makes our visual system better tuned to upright faces than inverted faces.”

Duchaine was surprised to get a different result when Claudio saw Thatcherized faces. In that case, Claudio performed better when those manipulated faces appeared upright. While the researchers say they don’t why this happened, they suspect that the Thatcher effect arises from different visual mechanisms than facial detection and identity matching—and that those different mechanisms must have different developmental trajectories.

In future studies, the researchers want to learn more about this difference as well as other kinds of judgments people make when they see faces, including facial expressions, age, sex, attractiveness, eye gaze direction, trustworthiness, and more. Using measures of what’s happening in Claudio’s brain when he sees faces, they also want to “see whether his current face processing depends on typical mechanisms.”

####

The work was supported by the Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth.

iScience, Duchaine et al.: “The development of upright face perception depends on evolved orientation-specific mechanisms and experience” https://www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext/S2589-0042(23)01840-0

iScience (@iScience_CP) is an open-access journal from Cell Press that provides a platform for original research and interdisciplinary thinking in the life, physical, and earth sciences. The primary criterion for publication in iScience is a significant contribution to a relevant field combined with robust results and underlying methodology. Visit http://www.cell.com/iscience. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

END

Even without a central brain, jellyfish can learn from past experiences like humans, mice, and flies, scientists report for the first time on September 22 in the journal Current Biology. They trained Caribbean box jellyfish (Tripedalia cystophora) to learn to spot and dodge obstacles. The study challenges previous notions that advanced learning requires a centralized brain and sheds light on the evolutionary roots of learning and memory.

No bigger than a fingernail, these seemingly simple jellies have a complex visual system with 24 eyes embedded in their bell-like body. Living ...

Jellyfish are more advanced than once thought. A new study from the University of Copenhagen has demonstrated that Caribbean box jellyfish can learn at a much more complex level than ever imagined – despite only having one thousand nerve cells and no centralized brain. The finding changes our fundamental understanding of the brain and could enlighten us about our own mysterious brains.

After more than 500 million years on Earth, the immense evolutionary success of jellyfish is undeniable. Still, we've always thought of them as simple creatures with very limited learning abilities.

The prevailing opinion is that ...

About The Study: In this study using a behavioral experiment designed to mimic a real-world imposter scam among 644 older adults, a sizable number of older adults engaged without skepticism. The results suggest that many older adults, including those without cognitive impairment, are vulnerable to fraud and scams.

Authors: Lei Yu, Ph.D., of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.35319)

Editor’s ...

About The Study: The results of this study of 220,000 American Indian and Alaska Native patients with Medicare insurance suggest a significant burden of cardiovascular disease and cardiometabolic risk factors. These findings highlight the critical need for future efforts to prioritize the cardiovascular health of this population.

Authors: Lauren A. Eberly, M.D., M.P.H., of the Indian Health Service in Gallup, New Mexico, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.15212/ZOONOSES-2023-0031

Announcing a new article publication for Zoonoses journal. Monkey B virus (BV) infection in humans and other macaque species has a mortality rate of approximately 80%. Because BV infects humans through bites, scratches, and other injuries inflicted by macaques, the simple and rapid diagnosis of BV in field laboratories is of great importance to protect veterinarians, laboratory researchers, and support personnels from the threat of infection.

Two recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) assays with a closed vertical flow (VF) visualization strip (RPA-VF-UL27 and RPA-VF-US6) were developed that target ...

A research group at the University of Helsinki and its partners have found a promising drug candidate for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor CDNF prolongs the lifespan of and alleviates disease symptoms in rats and mice in animal studies.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rapidly progressing fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Specifically, a selective degeneration of motoneurons occurs in the spinal cord, leading to muscle atrophy and paralysis. Most patients with ...

Researchers have made a significant finding in determining the genetic background of dilated cardiomyopathy in Dobermanns. This research helps us understand the genetic risk factors related to fatal diseases of the heart muscle and the mechanisms underlying the disease, and offers new tools for their prevention.

Researchers from the University of Helsinki and the Folkhälsan Research Center, together with their international partners, have identified the genetic background of dilated cardiomyopathy, a disease that enlarges the heart muscle, in dogs and humans.

Based ...

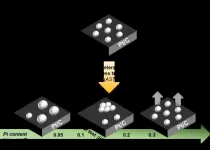

Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) hold promise as a replacement for fossil fueled engines in heavy-duty vehicles. Reducing the platinum content in catalysts is pivotal for scaling up in such applications. Yet, the degradation patterns of low platinum content catalysts remain poorly understood. A team of scientists conducted experiments to shed light on the degradation mechanisms associated with varying catalyst content, offering valuable insights. Their work is published in the journal Industrial Chemistry & Materials on 11 Aug 2023.

In ...

Palm oil is the world's most produced and consumed vegetable oil and everyone knows that its production can damage the environment. But do consumers have the full picture? In fact, replacing palm oil with rapeseed oil would require a four to five-fold increase in the amount of land needed. Research led by the University of Göttingen investigated the attitudes, beliefs and understanding about palm oil of the general public in Germany, and how this links to land use. The researchers show that people find it hard to know the consequences of their buying choices, even when extra information is supplied. The results were published in Sustainable ...

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Scientists studying Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have identified thousands of genetic variants in the genome in the development of this progressive neurodegenerative disease.

These variants are predominantly located in genomic regions that do not code for proteins, making it difficult to understand which variants confer individuals’ risk of AD. Non-coding variants were once thought to be “junk DNA” by scientists. In recent years, these variants have been appreciated for playing crucial roles in controlling gene expression across tissues and cell types. However, linking these non-coding variants to the genes they regulate and effects ...