(Press-News.org) MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Images

Highlights:

New Michigan State University research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that plants such as oak and poplar trees will emit more of a compound called isoprene as global temperatures climb.

Isoprene from plants represents the highest flux of hydrocarbons to the atmosphere behind methane.

Although isoprene isn’t inherently bad — it actually helps plants better tolerate insect pests and high temperatures — it can worsen air pollution by reacting with nitrogen oxides from automobiles and coal-fired power plants.

The new publication can help us better understand, predict and potentially mitigate the effects of increased isoprene emission as the planet warms.

It’s a simple question that sounds a little like a modest proposal.

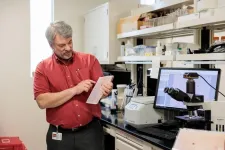

“Should we cut down all the oak trees?” asked Tom Sharkey, a University Distinguished Professor in the Plant Resilience Institute at Michigan State University.

Sharkey also works at the MSU-Department of Energy Plant Research Laboratory and in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

To be clear, Sharkey wasn’t sincerely suggesting that we should cut down all the oaks. Still, his question was an earnest one, prompted by his team’s latest research, which was published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team discovered that, on a warming planet, plants like oaks and poplars will emit more of a compound that exacerbates poor air quality, contributing to problematic particulate matter and low-atmosphere ozone.

The rub is that the same compound, called isoprene, can also improve the quality of clean air while making plants more resistant to stressors including insects and high temperatures.

“Do we want plants to make more isoprene so they’re more resilient, or do we want them making less so it’s not making air pollution worse? What’s the right balance?” Sharkey asked. “Those are really the fundamental questions driving this work. The more we understand, the more effectively we can answer them.”

Spotlight on isoprene

Sharkey has been studying isoprene and how plants produce it since the 1970s, when he was a doctoral student at Michigan State.

Isoprene from plants is the second-highest emitted hydrocarbon on Earth, only behind methane emissions from human activity. Yet most people have never heard of it, Sharkey said.

“It’s been behind the scenes for a long time, but it’s incredibly important,” Sharkey said.

It gained a little notoriety in the 1980s, when then-president Ronald Reagan falsely claimed trees were producing more air pollution than automobiles. Yet there was a kernel of truth in that assertion.

Isoprene interacts with nitrogen oxide compounds found in air pollution produced by coal-fired power plants and internal combustion engines in vehicles. These reactions create ozone, aerosols and other byproducts that are unhealthy for both humans and plants.

“There’s this interesting phenomenon where you have air moving across a city landscape, picking up nitrogen oxides, then moving over a forest to give you this toxic brew,” Sharkey said. “The air quality downwind of a city is often worse than the air quality in the city itself.”

Now, with support from the National Science Foundation, Sharkey and his team are working to better understand the biomolecular processes plants use to make isoprene. The researchers are particularly interested in how those processes are affected by the environment, especially in the face of climate change.

Prior to the team’s new publication, researchers understood that certain plants produce isoprene as they carry out photosynthesis. They also knew the changes that the planet is facing were having competing effects on isoprene production.

That is, increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere drives the rate down, while increasing temperatures accelerate the rate. One of the questions behind the MSU team’s new publication was essentially which one of these effects will win out.

“We were looking for a regulation point in the isoprene’s biosynthesis pathway under high carbon dioxide,” said Abira Sahu, the lead author of the new report and a postdoctoral research associate in Sharkey’s research group.

“Scientists have been trying to find this for a long time,” Sahu said. “And, finally, we have the answer.”

“For the biologists out there, the crux of the paper is that we identified the specific reaction slowed by carbon dioxide, CO2,” Sharkey said.

“With that, we can say the temperature effect trumps the CO2 effect,” he said. “By the time you’re at 95 degrees Fahrenheit — 35 degrees Celsius — there’s basically no CO2 suppression. Isoprene is pouring out like crazy.”

In their experiments, which used poplar plants, the team also found that when a leaf experienced warming of 10 degrees Celsius, its isoprene emission increased more than tenfold, Sahu said.

“Working with Tom, you realize plants really do emit a lot of isoprene,” said Mohammad Mostofa, an assistant professor who works in Sharkey’s lab and was another author of the new report.

The discovery will help researchers better anticipate how much isoprene plants will emit in the future and better prepare for the impacts of that. But the researchers also hope it can help inform the choices people and communities make in the meantime.

“We could be doing a better job,” Mostofa said.

At a place like MSU, which is home to more than 20,000 trees, that could mean planting fewer oaks in the future to limit isoprene emissions.

As for what we do about the trees already emitting isoprene, Sharkey does have an idea that doesn’t involve cutting them down.

“My suggestion is that we should do a better job controlling nitrogen oxide pollution,” Sharkey said.

Sarathi Weraduwage, a former postdoctoral researcher in Sharkey’s lab who is now an assistant professor at Bishop’s University in Quebec, also contributed to the research.

By Matt Davenport

Read on MSUToday.

###

Michigan State University has been advancing the common good with uncommon will for more than 165 years. One of the world's leading research universities, MSU pushes the boundaries of discovery to make a better, safer, healthier world for all while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 400 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

END

MSU research shows plants could worsen air pollution on a warming planet

2023-10-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Barrow Neurological Institute receives $16.7 million NIH award to help coordinate new national ALS research consortium

2023-10-05

The purpose of the award is to create the Access for All in ALS (ALL ALS) Consortium to conduct clinical research that will include ALS patients nationwide, generating a longitudinal biorepository linked to detailed clinical information that will be made available to research scientists throughout the world using a web-based portal. As part of this new consortium Barrow will manage half of 34 clinical sites in the study which spans the U.S. and Puerto Rico. The consortium will be led by researchers at Barrow, Massachusetts General Hospital and Columbia University.

“Barrow Neurological Institute is honored to be selected by the NIH to help coordinate this ...

How to protect self-esteem when a career goal dies

2023-10-05

Many people fail at achieving their early career dreams. But a new study suggests that those failures don’t have to harm your self-esteem if you think about them in the right way.

Researchers found that people who viewed career goal failures as a steppingstone to new opportunities never lost self-esteem, no matter how many times they failed. But those who thought their failures left them worse off showed a drop-off in how they felt about themselves.

“It’s not how many times you have had to give up. It is how you felt about the failures, and whether you thought they led to something better for you,” ...

Ultrasensitive blood test detects ‘pan-cancer’ biomarker

2023-10-05

Pathology experts engineered an ultrasensitive test capable of detecting a highly specific biomarker found in multiple common cancers

In collaboration with cancer researchers across the country and the globe, the team evaluated the tool’s ability to detect the biomarker in ovarian cancer, gastroesophageal cancer, colon cancer, and other cancers

Diagnostic assays have potential for early cancer detection, monitoring, and prognostics

Marker ‘LINE-1 ORF1p’ is a protein encoded by a human transposon that has further potential applications in tissue diagnostics and may also facilitate treatment of cancers for which no accurate biomarkers ...

Insilico Medicine founder and CEO Alex Zhavoronkov, Ph.D., to present on AI drug discovery at LSX Nordic Congress

2023-10-05

Alex Zhavoronkov, Ph.D., founder and CEO of Insilico Medicine (“Insilico”) will present at the 6th LSX Nordic Conference happening in Copenhagen Oct. 10-11. Zhavoronkov, a leader in generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for drug discovery and biomarker development, will present on Oct. 11, 2pm CET on “‘How Artificial Intelligence is Shaping the Future of Drug Discovery, Design, and Development.”

The LSX Nordic Congress is a leading strategy, investment and partnering conference for the Nordic region connecting life science and healthcare ...

Grape consumption benefits eye health in human study of older adults

2023-10-05

In a recent randomized, controlled human study, consuming grapes for 16 weeks improved key markers of eye health in older adults. The study, published in the scientific journal Food & Function looked at the impact of regular consumption of grapes on macular pigment accumulation and other biomarkers of eye health.[1] This is the first human study on this subject, and the results reinforce earlier, preliminary studies where consuming grapes was found to protect retinal structure and function.[2]

Science has shown that an aging population has a higher risk of eye disease and vision problems. Key risk factors for eye disease include 1) oxidative ...

Don’t feel appreciated by your partner? Relationship interventions can help

2023-10-05

When we’re married or in a long-term romantic relationship, we may eventually come to take each other for granted and forget to show appreciation. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign finds that it doesn’t have to stay this way.

The study examined why perceived gratitude from a spouse or romantic partner changes over time, and whether it can be improved through relationship intervention programs.

“Gratitude almost seems to be a secret sauce to relationships, and an important piece to the puzzle of romantic relationships that hasn’t gotten much attention ...

Study confirms age of oldest fossil human footprints in North America

2023-10-05

The 2021 results began a global conversation that sparked public imagination and incited dissenting commentary throughout the scientific community as to the accuracy of the ages.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist ...

More than 10,000 pre-Columbian earthworks remain hidden throughout Amazonian forests

2023-10-05

More than 10,000 Pre-Columbian archaeological sites likely rest undiscovered throughout the Amazon basin, estimates a new study. The findings, derived from remote sensing data and predictive spatial modeling, address questions about the influence of pre-Columbian societies on the Amazon region. “The massive extent of archaeological sites and widespread human-modified forests across Amazonia is critically important for establishing an accurate understanding of interactions between human societies, Amazonian forests, and Earth’s climate,” write the authors. ...

New, independent ages confirm antiquity of ancient human footprints at White Sands

2023-10-05

New radiocarbon (14C) and optically simulated luminescence ages have confirmed the controversial antiquity of the ancient human footprints discovered in White Sands National Park, and reported in a study in 2021. Addressing the widespread criticism of their previous study, researchers report that the independent ages from multiple resolved sources conclusively show that the footprints were left behind between roughly 23,000 and 20,000 years ago, demonstrating that humans were present in southern North America during the Last Glacial ...

Special Issue: Ancient DNA

2023-10-05

In this Special Issue of Science, three Reviews highlight how recent advances in the field of ancient DNA have greatly advanced our understanding of the evolutionary history of many plants and animals, including our own species. “This special issue examines the changing landscape of how ancient DNA (aDNA) is studied today, including previously untapped sources, improvements in technology, and ethical challenges, and what we’ve learned about ourselves though ancient DNA,” write Corinne Simonti and Madeleine ...