(Press-News.org) Increased salinity usually spells trouble for freshwater insects like mayflies. A new study from North Carolina State University finds that the lack of metabolic responses to salinity may explain why some freshwater insects often struggle in higher salinity, while other freshwater invertebrates (like mollusks and crustaceans) thrive. Salinity in this case refers to the concentrations of all the salts in an aquatic environment, not just sodium.

“Freshwater habitats in general are getting saltier for a number of reasons, including road salt and agricultural runoff, extraction of coal and natural gas, drought, and sea level rise,” says David Buchwalter, professor of toxicology at NC State and corresponding author of the research. “Freshwater insects and other organisms that live in these systems are used as indicators of the ecosystem’s health. When these systems get saltier, we see that insect diversity decreases, but we aren’t sure why.”

Aquatic animals (including insects and crustaceans) must constantly maintain the correct balance of water and salts within their body – a process called osmoregulation. Theoretically, the most favorable environment for aquatic animals would be one where external salinity levels are close to those inside the animal. That way the animal doesn’t have to work as hard to maintain osmoregulation.

However, the opposite seems to be true for freshwater insects – higher salinity is always associated with increased rates of ion uptake in insects, but it is also associated with developmental delays or death.

“We thought that freshwater insects might be shifting so much of their energy toward osmoregulation in saltier environments that they cannot grow or thrive,” Buchwalter says. “So we measured the metabolic rates of crustaceans and insects in dilute and saline environments to see if metabolic responses to salinity were similar.”

The team looked at three types of freshwater animals – two species of gammarid, or “scud,” which is a small freshwater crustacean; one freshwater snail; and three aquatic insect species.

In the first test, they measured the animals’ metabolism by placing them in waters with different concentrations of salt ions and looking at their rates of oxygen consumption. They observed that more dilute conditions made the crustaceans and snail breathe harder, increasing their metabolism, while insects’ metabolic rates were constant regardless of salinity.

Next, the team looked at whether an increase in breathing rates was linked to the transport of a particular ion. Radioactive isotopes of the salt ions calcium and sodium allowed the researchers to measure how much and how quickly the animals took up different ions.

The researchers found that calcium was the key driver of non-insects’ increased metabolism in lower salinity. In other words, the crustaceans and snail worked harder to transport the calcium ions they required in an environment where calcium was harder to find.

In contrast, the insects’ metabolic rates remained constant in both saline and dilute environments, even though they had a higher calcium ion transport rate in the saline environment. Insects seem to have very little demand for calcium; in fact, previous research has shown that excess calcium is potentially toxic to them.

The researchers think that the animals’ use of internal energy, or active transport, when moving the salts could be the explanation.

“When we see non-insects’ metabolisms increase in dilute environments, it could be due to the fact that they have to work harder to take in more calcium,” Buchwalter says. “And while it seems counterintuitive, the opposite is true for insects who are working harder in a more saline environment to maintain equilibrium, although their respiration rates don’t increase. Instead, they appear to utilize resources that would otherwise be dedicated to growth and development to ‘undo’ excessive ion uptake when things get saltier.

“Moving salt ions has an energy cost to the animal,” Buchwalter says. “So for freshwater insects, the idea that organisms should thrive in environments that are close to their internal salinity is wrong. Additionally, their low demand for calcium may help them thrive in very dilute environments where insects typically dominate the ecology. In contrast, low calcium appears to be stressful for the crustaceans and snail in this study. It is fascinating that species living in the same habitats can have such different physiologies.”

Future work will explore whether these physiological differences are based on the ancestry of the organisms tested, or the use of calcium in their exoskeletons/shells.

The work appears in the Journal of Experimental Biology and was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant IOS 1754884. First author and Ph.D. candidate Jamie Cochran was supported by a Goodnight Doctoral Fellowship. Catelyn Banks, formerly a student at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, also contributed to the work.

-peake-

Note to editors: An abstract follows.

“Respirometry reveals major lineage-based differences in the energetics of osmoregulation in aquatic invertebrates”

DOI: 10.1242/jeb.246376

Authors: Jamie Cochran, David Buchwalter, North Carolina State University; Catelyn Banks, North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics

Published: Oct. 5, 2023 in the Journal of Experimental Biology

Abstract:

All freshwater organisms are challenged to control their internal balance of water and ions in strongly hypotonic environments. We compared the influence of external salinity on the M.O2 of three species of freshwater insects, one snail, and two crustaceans. Consistent with available literature, we find a clear decrease in M.O2 with increasing salinity in the snail Elimia sp. and crustaceans Hyalella azteca and Gammarus pulex (r(5)= -0.90, p=0.03). However, we show here that metabolic rates are generally unchanged by salinity in freshwater insects, whereas ion transport rates are positively correlated with higher salinities. In contrast, when we examined the ionic influx rates in freshwater snail and crustaceans, we found that Ca uptake rates were highest under the most dilute conditions, while Na uptake rates increased with salinity. In G. pulex exposed to a serially diluted ion matrix, calcium uptake rates were positively associated with oxygen consumption rates (r(5)=-0.93, p=0.02). This positive association between Ca uptake rate and oxygen consumption was also observed when conductivity was held constant, but Ca concentration was manipulated (1.7-17.3 mg Ca L-1) (r(5)=0.94, p=0.05). This finding potentially implicates the cost of calcium uptake as a driver of increased metabolic rate under dilute conditions in organisms with calcified exoskeletons and suggests major phyletic differences in osmoregulatory physiology. Freshwater insects may be energetically challenged by higher salinities, while lower salinities may be more challenging for other freshwater taxa.

END

Consistent metabolism may prove costly for insects in saltier water

2023-10-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Clinical trials: two arms are better than one

2023-10-06

The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) has responded critically to a reflection paper by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on the approval of new drugs based on single-arm studies. The EMA correctly points out that studies without a control arm are subject to bias and that, in general, it is hardly possible to estimate causal effects from them. However, it does not provide clear criteria for limiting drug approval based on such studies to extremely rare exceptional cases.

The FDA shows how to do it

There is also no recommendation on external controls - in contrast to guidance published ...

The efficient perovskite cells with a structured anti-reflective layer – another step towards commercialization on a wider scale

2023-10-06

Perovskite-based solar cells, widely considered as successors to the currently dominant silicon cells, due to their simple and cost-effective production process combined with their excellent performance, are now the subject of in-depth research. A team of scientists from the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy ISE and the Faculty of Physics at the University of Warsaw presented perovskite photovoltaic cells with significantly improved optoelectronic properties in the journal Advanced Materials and Interfaces. Reducing optical losses in the ...

BU researcher awarded $3.7 million to study how endothelial cell health impacts disease

2023-10-06

(Boston)—Naomi Hamburg, MD, the Joseph A. Vita Professor of Medicine at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, has been awarded a five-year, $3.7 million grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for her research study, “Endothelial Cell Health Across the Spectrum of Cardiometabolic Disease.”

Cardiometabolic diseases are a group of common but often preventable conditions including heart attack, stroke, diabetes, insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The escalating prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors including obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) ...

Autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders following COVID-19

2023-10-06

About The Study: COVID-19 was associated with a substantial risk for autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders in this retrospective cohort study, indicating that long-term management of patients with COVID-19 should include evaluation for such disorders.

Authors: Solam Lee, M.D., Ph.D., of Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine in Wonju, Republic of Korea, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website ...

Cancer research: Metabolite drives tumor development

2023-10-06

Cancer cells are chameleons. They completely change their metabolism to grow continuously. University of Basel scientists have discovered that high levels of the amino acid arginine drive metabolic reprogramming to promote tumor growth. This study suggests new avenues to improve liver cancer treatment.

The liver is a vital organ with many important functions in the body. It metabolizes nutrients, stores energy, regulates the blood sugar level and plays a crucial role in detoxifying and removing harmful components and drugs. Liver cancer is one of the world’s most lethal types of cancer. Conditions that cause liver cancer include obesity, excessive ...

Patterns in physician burnout

2023-10-06

About The Study: The findings of this survey study involving 1,373 physicians and three survey periods suggest that the physician burnout rate in the U.S. is increasing. This pattern represents a potential threat to the ability of the health care system to care for patients and needs urgent solutions.

Authors: Marcus V. Ortega, M.D., of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.36745)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including ...

Rise in overdose deaths increasingly affects those with lower educational attainment, RAND study finds

2023-10-06

Drug overdose deaths increased sharply among Americans without a college education and nearly doubled over a three-year period among those who don’t have a high school diploma, according to a new RAND Corporation study. The findings further highlight a potential association between the rise in drug overdose deaths and barriers to education access, a social determinant of health.

Lower educational attainment has been one of the socioeconomic factors historically associated with drug use and overdose deaths, but the emergence of fentanyl in street drugs and the rise of the COVID-19 ...

Deciphering the intensity of past ocean currents

2023-10-06

Details of past climate conditions are revealed to researchers not only by sediment samples from the ocean floor, but also by the surface of the seafloor, which is exposed to currents that are constantly altering it. Deposits shaped by near-bottom currents are called contourites. These sediment deposits contain information about past ocean conditions as well as clues to climate. Contourites are often found on continental slopes or around deep-sea mountains. But they can be found in any environment where strong currents occur near the seafloor. The mechanisms that control them are not yet well understood. ...

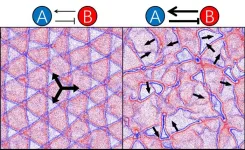

How bacteria can organize themselves

2023-10-06

In a recent study, scientists from the department Living Matter Physics at MPI-DS developed a model describing communication pathways in bacterial populations. Bacteria show an overall organizational pattern by sensing the concentration of chemicals in their environment and adapting their motion.

The structure only becomes visible on a higher level

“We modeled the non-reciprocal interaction between two bacterial species”, first author Yu Duan explains. “This means that species A is chasing species B, whereas B is aiming to repel from A”, he continues. The researchers found, that just this chase-and-avoid interaction is sufficient to form a structural pattern. The ...

Pulsars may make dark matter glow

2023-10-06

The central question in the ongoing hunt for dark matter is: what is it made of? One possible answer is that dark matter consists of particles known as axions. A team of astrophysicists, led by researchers from the universities of Amsterdam and Princeton, has now shown that if dark matter consists of axions, it may reveal itself in the form of a subtle additional glow coming from pulsating stars.

Dark matter may be the most sought-for constituent of our universe. Surprisingly, this mysterious form of matter, ...