(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Human sensory systems are very good at recognizing objects that we see or words that we hear, even if the object is upside down or the word is spoken by a voice we’ve never heard.

Computational models known as deep neural networks can be trained to do the same thing, correctly identifying an image of a dog regardless of what color its fur is, or a word regardless of the pitch of the speaker’s voice. However, a new study from MIT neuroscientists has found that these models often also respond the same way to images or words that have no resemblance to the target.

When these neural networks were used to generate an image or a word that they responded to in the same way as a specific natural input, such as a picture of a bear, most of them generated images or sounds that were unrecognizable to human observers. This suggests that these models build up their own idiosyncratic “invariances” — meaning that they respond the same way to stimuli with very different features.

The findings offer a new way for researchers to evaluate how well these models mimic the organization of human sensory perception, says Josh McDermott, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines.

“This paper shows that you can use these models to derive unnatural signals that end up being very diagnostic of the representations in the model,” says McDermott, who is the senior author of the study. “This test should become part of a battery of tests that we as a field are using to evaluate models.”

Jenelle Feather PhD ’22, who is now a research fellow at the Flatiron Institute Center for Computational Neuroscience, is the lead author of the open-access paper, which appears today in Nature Neuroscience. Guillaume Leclerc, an MIT graduate student, and Aleksander Mądry, the Cadence Design Systems Professor of Computing at MIT, are also authors of the paper.

Different perceptions

In recent years, researchers have trained deep neural networks that can analyze millions of inputs (sounds or images) and learn common features that allow them to classify a target word or object roughly as accurately as humans do. These models are currently regarded as the leading models of biological sensory systems.

It is believed that when the human sensory system performs this kind of classification, it learns to disregard features that aren’t relevant to an object’s core identity, such as how much light is shining on it or what angle it’s being viewed from. This is known as invariance, meaning that objects are perceived to be the same even if they show differences in those less important features.

“Classically, the way that we have thought about sensory systems is that they build up invariances to all those sources of variation that different examples of the same thing can have,” Feather says. “An organism has to recognize that they're the same thing even though they show up as very different sensory signals.”

The researchers wondered if deep neural networks that are trained to perform classification tasks might develop similar invariances. To try to answer that question, they used these models to generate stimuli that produce the same kind of response within the model as an example stimulus given to the model by the researchers.

They term these stimuli “model metamers,” reviving an idea from classical perception research whereby stimuli that are indistinguishable to a system can be used to diagnose its invariances. The concept of metamers was originally developed in the study of human perception to describe colors that look identical even though they are made up of different wavelengths of light.

To their surprise, the researchers found that most of the images and sounds produced in this way looked and sounded nothing like the examples that the models were originally given. Most of the images were a jumble of random-looking pixels, and the sounds resembled unintelligible noise. When researchers showed the images to human observers, in most cases the humans did not classify the images synthesized by the models in the same category as the original target example.

“They’re really not recognizable at all by humans. They don’t look or sound natural and they don’t have interpretable features that a person could use to classify an object or word,” Feather says.

The findings suggest that the models have somehow developed their own invariances that are different from those found in human perceptual systems. This causes the models to perceive pairs of stimuli as being the same despite their being wildly different to a human.

Idiosyncratic invariances

The researchers found the same effect across many different vision and auditory models. However, each of these models appeared to develop their own unique invariances. When metamers from one model were shown to another model, the metamers were just as unrecognizable to the second model as they were to human observers.

“The key inference from that is that these models seem to have what we call idiosyncratic invariances,” McDermott says. “They have learned to be invariant to these particular dimensions in the stimulus space, and it's model-specific, so other models don't have those same invariances.”

The researchers also found that they could induce a model’s metamers to be more recognizable to humans by using an approach called adversarial training. This approach was originally developed to combat another limitation of object recognition models, which is that introducing tiny, almost imperceptible changes to an image can cause the model to misrecognize it.

The researchers found that adversarial training, which involves including some of these slightly altered images in the training data, yielded models whose metamers were more recognizable to humans, though they were still not as recognizable as the original stimuli. This improvement appears to be independent of the training’s effect on the models’ ability to resist adversarial attacks, the researchers say.

“This particular form of training has a big effect, but we don’t really know why it has that effect,” Feather says. “That’s an area for future research.”

Analyzing the metamers produced by computational models could be a useful tool to help evaluate how closely a computational model mimics the underlying organization of human sensory perception systems, the researchers say.

“This is a behavioral test that you can run on a given model to see whether the invariances are shared between the model and human observers,” Feather says. “It could also be used to evaluate how idiosyncratic the invariances are within a given model, which could help uncover potential ways to improve our models in the future.”

###

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, a Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellowship, and a Friends of the McGovern Institute Fellowship.

END

Study: Deep neural networks don’t see the world the way we do

Images that humans perceive as completely unrelated can be classified as the same by computational models

2023-10-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Moffitt research finds non-small cell lung cancer drug lorlatinib targets additional protein

2023-10-16

TAMPA, Fla. — Targeted cancer drugs are widely used because of their ability to inhibit specific proteins involved in cancer development with fewer side effects compared to chemotherapy drugs. But targeted therapies can often inhibit other unknown proteins. These hidden targets may also contribute to the drug’s anticancer effects and potentially offer a path for the drug to be repurposed for other cancers controlled by the hidden target.

In a new study published in Cell Chemical Biology, Moffitt Cancer Center researchers demonstrate this, showing that the ROS1 inhibitor lorlatinib has activity against an additional protein called PYK2. The team also reveals the mechanisms of ...

Medicaid is a vital lifeline for adults with Down syndrome

2023-10-16

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Monday October 16, 2023

Contact:

Jillian McKoy, jpmckoy@bu.edu

Michael Saunders, msaunder@bu.edu

##

Life expectancy has increased substantially for people in the United States with Down syndrome, from a median age of 4 years old in the 1950s to 57 years old in 2019. This longer life span increases the need for adequate healthcare into adulthood for this population, the majority of whom are at high ...

American Society of Anesthesiologists recognizes Santhanam Suresh, M.D., MBA, FASA, with its Excellence in Education Award

2023-10-16

SAN FRANCISCO — The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) today presented Santhanam Suresh, M.D., MBA, FASA, with its 2023 Excellence in Education Award in recognition of his extraordinary educational contributions to advancing regional anesthesia and pain management in children. The award is presented annually to an ASA member who has made significant contributions to the specialty through excellence in teaching, development of new teaching methods or the implementation of innovative educational programs.

Dr. Suresh is the Arthur C. King professor and chair emeritus of pediatric anesthesiology ...

American Society of Anesthesiologists recognizes Karsten Bartels, M.D., Ph.D., MBA, with its 2023 James E. Cottrell Presidential Scholar Award

2023-10-16

SAN FRANCISCO — The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) today honored Karsten Bartels, M.D., Ph.D., MBA., with its 2023 James E. Cottrell Presidential Scholar Award in recognition of his exemplary research to improve patient outcomes in perioperative and critical care medicine and pain management. The award is presented annually to an ASA member who has dedicated their formative career to research.

Dr. Bartels is the Robert Lieberman Endowed Chair in Anesthesiology, vice chair of research and professor of anesthesiology with tenure at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) in Omaha. Additionally, he is the inaugural director of the Robert ...

Sansbury receives funding for dissertation study

2023-10-16

Amber B. Sansbury, a doctoral candidate in Mason's School of Education, received $24,576 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for the project: "Racial Identity Development of Young Black Children in Early Childhood Education: The Roles of Teachers and Families."

Colleen Vesely, Associate Professor, College of Education and Human Development (CEHD), is serving as Sansbury's adviser.

In this qualitative dissertation study, Sansbury will explore how family engagement vis-a-vis relationships between African American teachers and African American families supports racial socialization and young children's emergent racial ...

US Department of Energy selects the high performance data facility lead

2023-10-16

Today, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced the selection of the High Performance Data Facility (HPDF) hub, which will create a new scientific user facility specializing in advanced infrastructure for data-intensive science. The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab) will be the HPDF Hub Director and the lead infrastructure will be located at JLab. The project to build the Hub will be a partnership between JLab and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), and the two labs ...

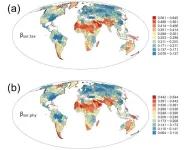

Scientists present the first set of global maps showing geographic patterns of beta-diversity in flowering plants

2023-10-16

Beta-diversity serves as a crucial metric for gauging shifts in species composition over spatial or temporal scales, bridging the spectrum between localized (alpha) and broader regional (gamma) diversity. In the fields of ecology, biogeography and conservation biology, to elucidate the origins and sustenance of geographic beta-diversity patterns, we need to explore both the taxonomic and phylogenetic beta-diversity at different evolutionary depths.

In an article published in the KeAi journal Plant Diversity, using a ...

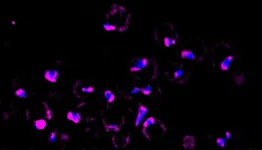

New biomarker predicts whether neurons will regenerate

2023-10-16

Neurons, the main cells that make up our brain and spinal cord, are among the slowest cells to regenerate after an injury, and many neurons fail to regenerate entirely. While scientists have made progress in understanding neuronal regeneration, it remains unknown why some neurons regenerate and others do not.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, a method that determines which genes are activated in individual cells, researchers from University of California San Diego School of Medicine have identified a new biomarker that can be used to predict whether ...

Peering inside cells to see how they respond to stress

2023-10-16

Imagine the life of a yeast cell, floating around the kitchen in a spore that eventually lands on a bowl of grapes. Life is good: food for days, at least until someone notices the rotting fruit and throws them out. But then the sun shines through a window, the section of the counter where the bowl is sitting heats up, and suddenly life gets uncomfortable for the humble yeast. When temperatures get too high, the cells shut down their normal processes to ride out the stressful conditions and live to feast on grapes on another, cooler day.

This “heat ...

Effectiveness of monovalent mRNA vaccines against Omicron XBB infection in Singaporean children

2023-10-16

About The Study: The results of this study including 121,000 Singaporean children ages 1 through 4 suggest that completion of a primary mRNA vaccine series provided protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although incidence of hospitalization and severe illness is low in this age group, there is potential benefit of vaccination in preventing infection and potential sequelae.

Authors: Liang En Wee, M.R.C.P., M.P.H., of the National Centre for Infectious Diseases in Singapore, is the corresponding author.

To access the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

[Press-News.org] Study: Deep neural networks don’t see the world the way we doImages that humans perceive as completely unrelated can be classified as the same by computational models