(Press-News.org) If you’ve ever belly-flopped into a pool, then you know: water can be surprisingly hard if you hit it at the wrong angle. But many species of kingfishers dive headfirst into water to catch their fishy prey. In a new scientific study in the journal Communications Biology, researchers compared the DNA of 30 different kingfisher species to zero in on the genes that might help explain the birds’ diet and ability to dive without sustaining brain damage.

The type of diving that kingfishers do-- what researchers call “plunge-diving”-- is an aeronautic feat. “It’s a high-speed dive from air to water, and it’s done by very few bird species,” says Chad Eliason, a research scientist at the Field Museum in Chicago and the study’s first author. But it’s a behavior that’s potentially risky.

“For kingfishers to dive headfirst the way they do, they must have evolved other traits to keep them from hurting their brains,” says Shannon Hackett, associate curator of birds at the Field Museum and the study’s senior author.

Not all kingfishers actually fish-- many species of these birds eat land-dwelling prey like insects, lizards, and even other kingfishers. Previously, co-authors Jenna McCollough and Michael Andersen, researchers from the University of New Mexico, led the team in using DNA to show that the groups of kingfishers that eat fish aren’t each others’ closest relatives within the kingfisher family tree. That means that kingfishers evolved their fishy diets-- and the diving abilities to procure them-- a number of separate times, rather than all evolving from one common fish-eating ancestor.

“The fact that there are so many transitions to diving is what makes this group both fascinating and powerful, from a scientific research perspective,” says Hackett. “If a trait evolves a multitude of different times independently, that means you have power to find an overarching explanation for why that is.”

For this study, the researchers-- including co-authors Lauren Mellenthin currently at Yale University, but who was an undergraduate intern at Field Museum at the time this research was conducted, Taylor Hains at the University of Chicago and Field Museum, Stacy Pirro at Iridian Genomes, and Michael Anderson and Jenna McCullough at the University of New Mexico-- examined the DNA of 30 species of kingfishers, both fish-eating and not.

“To get all the kingfisher DNA, we used specimens in the Field Museum’s collections,” says Eliason, who works in the Field’s Grainger Bioinformatics Center and Negaunee Integrative Research Center. “When our scientists do fieldwork, they take tissue samples from the bird specimens they collect, like pieces of muscle or liver. Those tissue samples are stored at the Field Museum, frozen in liquid nitrogen, to preserve the DNA.”

In the Field’s Pritzker DNA Laboratory, the researchers began the process of sequencing full genomes for each of the species, generating the entire genetic code of each bird. From there, they used software to compare the billions of base pairs making up these genomes to look for genetic variations that the diving kingfishers have in common.

The scientists found that the fish-eating birds had several modified genes associated with diet and brain structure. For instance, they found mutations in the birds’ AGT gene, which has been associated with dietary flexibility in other species, and the MAPT gene, which codes for tau proteins that relate to feeding behavior.

Tau proteins help stabilize tiny structures inside the brain, but the accumulation of too many tau proteins can be a bad thing. In humans, traumatic brain injuries and Alzheimer’s disease are associated with a buildup of tau. “I learned a lot about tau protein when I was the concussion manager of my son’s hockey team,” says Hackett. “I started to wonder, why don’t kingfishers die because their brains turn to mush? There’s gotta be something they're doing that protects them from the negative influences of repeatedly landing on their heads on the water’s surface.”

Hackett suspects that tau proteins may be something of a double-edged sword. “The same genes that keep your neurons in your brain in all nice and ordered are the things that fail when you get repeated concussions if you're a football player or if you get Alzheimer's,” she says. “My guess is there’s some sort of strong selective pressure on those proteins to protect the birds’ brains in some way.”

Now that these correlated genomic variations have been identified, says Hackett, “the next question is, what do the mutations in these birds’ genes do to the proteins that are being produced? What shape changes are there? What is going on to compensate in a brain for the concussive forces?”

“Now, we know which of the underlying genes are shifting that help create the differences that we see across the kingfisher family,” says Eliason. “But now that we know which genes to look at, it created more mysteries. That’s how science works.”

In addition to a better understanding of kingfisher genetics and potential implications for understanding brain injuries, Hackett says that this study is important because it highlights the value of museum collections.

“One of the specimens we got DNA from in this study is thirty years old. At the time it was collected, we couldn’t do anywhere near the kind of analyses we can do today-- we couldn’t even do some of this stuff five years ago,” says Hackett. “It traces back to the ability of individual specimens to tell new stories through time. And who knows what we’ll be able to learn from these specimens in the future? That’s why I love museum collections.”

###

END

Two different regions of the brain are critical to integrating semantic information while reading, which could shed more light on why people with aphasia have difficulty with semantics, according to new research from UTHealth Houston.

The study, led by first author Elliot Murphy, PhD, postdoctoral research fellow in the Vivian L. Smith Department of Neurosurgery with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, and senior author Nitin Tandon, MD, professor and chair ad interim of the department in the medical school, was published today in Nature Communications.

Language depends largely on the integration of vocabulary across multiple words ...

It's viable to produce low-cost, lightweight solar panels that can generate energy in space, according to new research from the Universities of Surrey and Swansea.

The first study of its kind followed a satellite over six years, observing how the panels generated power and weathered solar radiation over 30,000 orbits.

The findings could pave the way for commercially viable solar farms in space.

Professor Craig Underwood, Emeritus Professor of Spacecraft Engineering at the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey, said:

“We are very pleased that a mission designed to last one year is still working after six. These detailed data ...

Bacterial diversity in the gut plays an important role in human health. The crucial question, however, is where are the sources of this diversity? It is known that an important part of the maternal microbiome is transferred to the baby at birth, and the same happens during the breastfeeding period via breast milk. Further sources were yet to be discovered. However, a team led by Wisnu Adi Wicaksono and Gabriele Berg from the Institute of Environmental Biotechnology at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz) has now succeeded in proving that plant microorganisms from fruit and vegetables contribute to the human microbiome. They report this in a study published in ...

Patients with a dysfunctional aortic heart valve who received a new, prosthetic valve through a minimally invasive procedure had similar outcomes at five years as those who underwent open-heart surgery, a new study shows.

The international multicenter study, with key contributions by the Cedars-Sinai heart team and published in The New England Journal of Medicine, offers a more complete picture to the ongoing dialogue comparing the minimally invasive heart procedure—called transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or TAVR—to open-heart surgery.

“Our data at five years validate that TAVR is a good alternative to open-heart surgery in younger patients with aortic ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. – Using anonymized smartphone data from nearly 10,000 police officers in 21 large U.S. cities, research from Indiana University finds officers on patrol spend more time in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

“Research on policing has focused on documented actions such as stops and arrests – less is known about patrols and presence,” said Kate Christensen, assistant professor of marketing at the IU Kelley School of Business.

“Police have discretion in deciding where law enforcement is provided within America’s cities,” she said. “Where police officers are located matters, because it affects ...

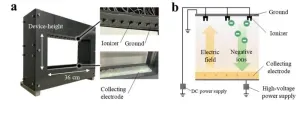

A novel device developed by researchers from Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, and Chiba University in a new study utilizes ions and an electric field to effectively capture infectious droplets and aerosols, while letting light and sound pass through to allow communication. The innovation is significant in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, since it shows promise in preventing airborne infection while facilitating communication.

Airborne infections, such as H1N1 influenza, SARS, and COVID-19, are spread by aerosols ...

Remember when your parents used to say, “Eat your greens, they are good for you”? Well, they were really onto something. Several studies have shown that higher intakes of cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, one of the most widely consumed vegetables in the United States, are associated with reduced risks of diseases such as diabetes and cancer, thanks to their organosulfur compounds, such as glucosinolates and isothiocyanates that exhibit a broad spectrum of bioactivities including antioxidant activity. However, few studies have focused on ...

A lack of clarity around sustainability reporting is allowing ASX-listed companies to retrospectively alter figures, ensuring CEO bonus pay tied to these metrics is realised, new research suggests.

Sustainability reports serve as critical tools for investors, regulators and other stakeholders to gauge a company's environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. They highlight issues such as environmental pollution and worker safety that might otherwise be overlooked.

Close to 90% of ASX top 200 companies provide detailed ESG information. Many of these ...

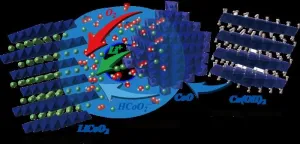

Layered lithium cobalt oxide, a key component of lithium-ion batteries, has been synthesized at temperatures as low as 300°C and durations as short as 30 minutes.

Lithium ion batteries (LIB) are the most commonly used type of battery in consumer electronics and electric vehicles. Lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) is the compound used for the cathode in LIB for handheld electronics. Traditionally, the synthesis of this compound requires temperatures over 800°C and takes 10 to 20 hours to complete.

A team of researchers at Hokkaido University and Kobe University, led by Professor Masaki Matsui at Hokkaido University’s Faculty of Science, have developed a new method to ...

Harnessing new advances in genomic surveillance technology could help detect the rise of deadly ‘superbugs’ and slow their evolution and spread, improving global health outcomes, a new Australian study suggests.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to the medicines and chemicals we use to kill them. These ‘superbugs’ make infections harder to treat and increase the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death.

Without significant intervention, global annual deaths involving antimicrobial resistance are estimated ...