(Press-News.org) Ever since the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, physicists have wanted to build new particle colliders to better understand the properties of that elusive particle and probe elementary particle physics at ever-higher energy scales.

The trick is, doing so takes energy – a lot of it. A typical collider takes hundreds of megawatts – the equivalent of tens of millions of modern lightbulbs – to operate. That's to say nothing of the energy it takes to build the devices, and it all adds up to one thing: A lot of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Now, researchers from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have thought through how to make one proposal, the Cool Copper Collider (C3), more energy efficient.

To understand how to do so, they considered three key aspects that apply to any accelerator design: how scientists would operate the collider, how the collider itself is built in the first place and even where the collider is built – which turns out to have a significant, if indirect, impact on the project's overall carbon footprint.

"When discussing big science, it's mandatory now to think not only in terms of financial costs, but also environmental impact," said Caterina Vernieri, an assistant professor at SLAC and one of the co-authors of the new paper, which was published in PRX Energy.

Emilio Nanni, an assistant professor at SLAC and another co-author, agreed. "As scientists we all hope to inspire the public and future generations not only through our discoveries, but also through our actions," Nanni said. "This requires that we consider both the potential scientific impact and the overall impact on our community." Making facilities more sustainable, he said, will help achieve both goals.

A plethora of options

C3 is one of a number of different proposals for a next-generation accelerator capable of probing the Higgs and beyond, although they all follow one of two basic designs: linear accelerators, such as C3and the proposed International Linear Collider, and synchrotrons, or future circular accelerators, such as the Future Circular Collider or the Circular Electron Positron Collider.

Each has their advantages and disadvantages. Notably, synchrotrons can re-circulate particle beams, meaning they can collect data over many loops. However, they hit a limit, because charged particles like protons and electrons lose energy when their paths are bent into a circle, driving up power consumption. Linear accelerators don't have the energy loss problem allowing them to achieve higher energy and open up the possibility for new measurements, but they use the beam only once and to achieve higher data rates they need to work with intense beams.

C3 aims to solve the length-versus-energy limitations of most linear accelerators with a new design, including more precisely tailored electromagnetic fields fed into the accelerator at more points as well as a new cryogenic cooling system. The project also aims to use more interchangeable parts and a construction approach that could significantly lower costs, ultimately resulting in a relatively low-cost and small collider – as short as about five miles – that could nonetheless probe the extreme frontiers of particle physics.

Making big physics more sustainable

Still, the proposed C3 collider would take a lot of resources to build and operate, so its proponents addressed a growing concern by taking the carbon footprint of major physics projects into account, starting with how they would operate the accelerator itself.

Historically, physicists did not pay much attention to how they operated accelerators, at least in terms of energy efficiency. The SLAC and Stanford team found, however, that subtle changes, such as changing the structure of the particle beam and making improvements in the operation of klystrons, which create the electromagnetic fields that drive the beam, could make a difference. Taken together, these improvements could cut C3's power needs from around 150 megawatts to perhaps 77 megawatts, or nearly in half. "I would happy with 50% of that," Vernieri said.

On the other hand, the team found, construction itself is likely to be responsible for the bulk of the carbon footprint for C3– especially as the world shifts to using more renewable energy. The researchers suggest that using different materials, such as different forms of concrete, as well as attending to how materials are manufactured and transported, could help lower the global warming impact. C3 is also significantly smaller than other accelerator proposals – only eight kilometers long – which would reduce the overall use of materials and allow builders to select sites that could simplify and speed up construction.

The researchers also considered where the C3 project would be located, since that could affect the mix of fossil-fuel versus renewable energy that powered the collider, or potentially building a dedicated solar farm that would, along with an energy storage system, cover the accelerator's needs.

How colliders stack up

Finally, the SLAC-Stanford team looked at how C3 might compare with other future collider proposals, as well as how linear and circular colliders compare, when each collider performs similar measurements.

Based on their analysis and similar sustainability studies for other accelerators, the team found that construction is likely to be the main driver of a project's carbon footprint, but that circular colliders capable of similar physics goals would generally have higher emissions related to construction. Likewise, shorter accelerators such as C3 and another proposal, the Compact Linear Collider, would have less global warming potential compared to longer ones.

"It's so new as a field," Vernieri said of studying the sustainability of physics projects, but a necessary one. "There is a whole new discussion at least posing the question of the carbon footprint of particle physics."

END

Physicists ask: Can we make a particle collider more energy efficient?

2023-11-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study shows that smoking ‘stops’ cancer-fighting proteins, causing cancer and making it harder to treat

2023-11-03

November 3, TORONTO — Scientists at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) have uncovered one way tobacco smoking causes cancer and makes it harder to treat by undermining the body’s anti-cancer safeguards.

Their new study, published today in Science Advances, links tobacco smoking to harmful changes in DNA called ‘stop-gain mutations’ that tell the body to stop making certain proteins before they are fully formed.

They found that these stop-gain mutations were especially prevalent in genes known as ‘tumour-suppressors’, ...

How salt from the Caribbean affects our climate

2023-11-03

Joint press release by MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen and GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel

The distribution of salt by ocean currents plays a crucial role in regulating the global climate. This is what researchers from Dalhousie University in Canada, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen have found in a new study. ...

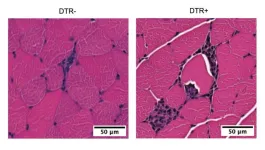

Some benefits of exercise stem from the immune system

2023-11-03

The connection between exercise and inflammation has captivated the imagination of researchers ever since an early 20th-century study showed a spike of white cells in the blood of Boston marathon runners following the race.

Now, a new Harvard Medical School study published Nov. 3 in Science Immunology may offer a molecular explanation behind this century-old observation.

The study, done in mice, suggests that the beneficial effects of exercise may be driven, at least partly, by the immune system. It shows that muscle inflammation caused by exertion mobilizes inflammation-countering T cells, or Tregs, which enhance the muscles’ ability to use ...

Seeing the unseen: How butterflies can help scientists detect cancer

2023-11-03

There are many creatures on our planet with more advanced senses than humans. Turtles can sense Earth’s magnetic field. Mantis shrimp can detect polarized light. Elephants can hear much lower frequencies than humans can. Butterflies can perceive a broader range of colors, including ultraviolet (UV) light.

Inspired by the enhanced visual system of the Papilio xuthus butterfly, a team of researchers have developed an imaging sensor capable of “seeing” into the UV range inaccessible to human eyes. The design of the sensor uses stacked photodiodes and perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) capable of imaging different wavelengths ...

nTIDE October 2023 Jobs Report: People with disabilities maintain job gains as economy cools

2023-11-03

East Hanover, NJ – November 3, 2023 – Experts reported little change in October’s employment indicators, as people with disabilities extended their historic highs into the fall, according to today’s National Trends in Disability Employment (nTIDE) – semi-monthly update issued by Kessler Foundation and the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability (UNH-IOD). As anti-inflationary measures exert their cooling effects on the economy, people with disabilities are striving to maintain their gains in the post-pandemic labor market.

Month-to-Month nTIDE Numbers (comparing September 2023 to October 2023)

Based on ...

Large herbivores such as elephants, bison and moose contribute to tree diversity

2023-11-03

Using global satellite data, a research team has mapped the tree cover of the world’s protected areas. The study shows that regions with abundant large herbivores in many settings have a more variable tree cover, which is expected to benefit biodiversity overall.

Maintaining species-rich and resilient ecosystems is key to preserving biodiversity and mitigating climate change. Here, megafauna – the part of the animal population in an area that is made up of the largest animals – plays an important role. In a new study published in the scientific journal One Earth, an international research team, of which Lund University is a part, has investigated the intricate interplay ...

The kids aren't alright: Saplings reveal how changing climate may undermine forests

2023-11-03

As climate scientist Don Falk was hiking through a forest, the old, green pines stretched overhead. But he had the feeling that something was missing. Then his eyes found it: a seedling, brittle and brown, overlooked because of its lifelessness. Once Falk's eyes found one, the others quickly fell into his awareness. An entire generation of young trees had died.

Falk – a professor in the UArizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment, with joint appointments in the Laboratory ...

Novel approach promises significant advance in treating autoimmune brain inflammation

2023-11-03

Researchers at DZNE and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin have pioneered a novel treatment for the most common autoimmune encephalitis. By reprogramming white blood cells to target and eliminate disease-causing cells, the approach offers a new level of precision and efficiency. The technique has proven successful in laboratory studies, clinical trials in humans are already being planned.

NMDA receptor encephalitis is the most common form of antibody-caused brain disease, in which antibodies suddenly attack the brain, thus turning against the patient’s own body. “In ...

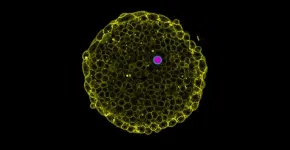

UC Santa Barbara researchers can now visualize osmotic pressure in living tissue

2023-11-03

In order to survive, organisms must control the pressure inside them, from the single-cell level to tissues and organs. Measuring these pressures in living cells and tissues in physiological conditions is a challenge.

In research that has its origin at UC Santa Barbara, scientists now at the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) at the Technical University in Dresden (TU Dresden), Germany, report in the journal Nature Communications a new technique to ‘visualize’ these pressures as organisms develop. These measurements can help understand how cells and tissues ...

A project that could touch all corners of Texas

2023-11-03

Texas is a huge state. And with that size comes soil diversity, supply chain delays, climate differences, material and labor costs and many other things to consider when evaluating the budget for a highway project.

To account for all of these variables, a University of Texas at Arlington researcher is building a price estimation and visualization tool for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) through a $200,000 U.S. Department of Transportation grant. Mohsen Shandashti, associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, is leading a team to develop that tool, which ...