(Press-News.org) A UK-based team of Scientists, led by experts from the University of Nottingham and Imperial College London, have completed construction of a synthetic chromosome as part of a major international project to build the world’s first synthetic yeast genome.

The work, which is published in Cell Genomics, represents completion of one of the 16 chromosomes of the yeast genome by the UK team, which is part of the biggest project ever in synthetic biology; the international synthetic yeast genome collaboration.

The collaboration, known as 'Sc2.0' has been a 15-year project involving teams from around the world (UK, US, China, Singapore, UK, France and Australia), working together to make synthetic versions of all of yeast's chromosomes. Alongside this paper, another 9 publications are also released today from other teams describing their synthetic chromosomes. The final completion of the genome project - the largest synthetic genome ever - is expected next year.

This effort is the first to build a synthetic genome of a eukaryote - a living organism with a nucleus, such as animals, plants and fungi. Yeast was the organism of choice for the project as it has a relatively compact genome and has the innate ability to stitch DNA together, allowing the researchers to build synthetic chromosomes within the yeast cells.

Humans have a long history with yeast, having domesticated it for baking and brewing over thousands of years and, more recently, using it for chemical production and as a model organism for how our own cells work. This relationship means that we know more about the genetics of yeast than any other organism. These factors made yeast the obvious candidate.

The UK-based team, led by Dr Ben Blount from the University of Nottingham and Professor Tom Ellis at Imperial College London, have now reported completion of their chromosome, synthetic chromosome XI. The project to build the chromosome has taken 10 years and the DNA sequence constructed consists of around 660,000 base pairs – which are the ‘letters’ making up the DNA code.

The synthetic chromosome has replaced one of the natural chromosomes of a yeast cell and, after a painstaking debugging process, now allows the cell to grow with the same fitness level as a natural cell. The synthetic genome will not only help scientists to understand how genomes function, but it will have many applications.

Rather than being a straight copy of the natural genome, the Sc2.0 synthetic genome has been designed with new features that give cells novel abilities not found in nature. One of these features allows researchers to force the cells to shuffle their gene content, creating millions of different versions of the cells with different characteristics. Individuals can then be picked with improved properties for a wide range of applications in medicine, bioenergy and biotechnology. The process is effectively a form of super-charged evolution.

The team has also shown that its chromosome can be repurposed as a new system to study extrachromosomal circular DNAs (eccDNAs). These are free-floating DNA circles that have “looped out” of the genome and are being increasingly recognised as factors in ageing and as a cause of malignant growth and chemotherapeutic drug resistance in many cancers, including glioblastoma brain tumours.

Dr Ben Blount, one of the lead scientists on the project, is an Assistant Professor in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham. He said: “The synthetic chromosomes are massive technical achievements in their own right, but will also open up a huge range of new abilities for how we study and apply biology. This could range from creating new microbial strains for greener bioproduction, through to helping us understand and combat disease.

“The synthetic yeast genome project is a fantastic example of science on a large scale that has been achieved by a large group of researchers from around the world. It’s been a great experience to be part of such a monumental effort, where all involved were striving towards the same shared goal.”

Professor Tom Ellis from the Centre for Synthetic Biology and Department of Bioengineering at Imperial College London, said: "By constructing a redesigned chromosome from telomere to telomere, and showing it can replace a natural chromosome just fine, our team's work establishes the foundations for designing and making synthetic chromosomes and even genomes for complex organisms like plants and animals."

As well as the leads of Nottingham and Imperial College London, the UK team also includes scientists from the universities of Edinburgh, Cambridge, and Manchester in the UK, as well as John Hopkins University and New York University Langone Health in the USA and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Querétaro in Mexico.

The work was funded by the BBSRC.

A UK-based team of Scientists, led by experts from the University of Nottingham and Imperial College London, have completed construction of a synthetic chromosome as part of a major international project to build the world’s first synthetic yeast genome.

The work, which is published in Cell Genomics, represents completion of one of the 16 chromosomes of the yeast genome by the UK team, which is part of the biggest project ever in synthetic biology; the international synthetic yeast genome collaboration.

The collaboration, known as 'Sc2.0' has been a 15-year project involving teams from around the world (UK, US, China, Singapore, UK, France and Australia), working together to make synthetic versions of all of yeast's chromosomes. Alongside this paper, another 9 publications are also released today from other teams describing their synthetic chromosomes. The final completion of the genome project - the largest synthetic genome ever - is expected next year.

This effort is the first to build a synthetic genome of a eukaryote - a living organism with a nucleus, such as animals, plants and fungi. Yeast was the organism of choice for the project as it has a relatively compact genome and has the innate ability to stitch DNA together, allowing the researchers to build synthetic chromosomes within the yeast cells.

Humans have a long history with yeast, having domesticated it for baking and brewing over thousands of years and, more recently, using it for chemical production and as a model organism for how our own cells work. This relationship means that we know more about the genetics of yeast than any other organism. These factors made yeast the obvious candidate.

The UK-based team, led by Dr Ben Blount from the University of Nottingham and Professor Tom Ellis at Imperial College London, have now reported completion of their chromosome, synthetic chromosome XI. The project to build the chromosome has taken 10 years and the DNA sequence constructed consists of around 660,000 base pairs – which are the ‘letters’ making up the DNA code.

The synthetic chromosome has replaced one of the natural chromosomes of a yeast cell and, after a painstaking debugging process, now allows the cell to grow with the same fitness level as a natural cell. The synthetic genome will not only help scientists to understand how genomes function, but it will have many applications.

Rather than being a straight copy of the natural genome, the Sc2.0 synthetic genome has been designed with new features that give cells novel abilities not found in nature. One of these features allows researchers to force the cells to shuffle their gene content, creating millions of different versions of the cells with different characteristics. Individuals can then be picked with improved properties for a wide range of applications in medicine, bioenergy and biotechnology. The process is effectively a form of super-charged evolution.

The team has also shown that its chromosome can be repurposed as a new system to study extrachromosomal circular DNAs (eccDNAs). These are free-floating DNA circles that have “looped out” of the genome and are being increasingly recognised as factors in ageing and as a cause of malignant growth and chemotherapeutic drug resistance in many cancers, including glioblastoma brain tumours.

Dr Ben Blount, one of the lead scientists on the project, is an Assistant Professor in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham. He said: “The synthetic chromosomes are massive technical achievements in their own right, but will also open up a huge range of new abilities for how we study and apply biology. This could range from creating new microbial strains for greener bioproduction, through to helping us understand and combat disease.

“The synthetic yeast genome project is a fantastic example of science on a large scale that has been achieved by a large group of researchers from around the world. It’s been a great experience to be part of such a monumental effort, where all involved were striving towards the same shared goal.”

Professor Tom Ellis from the Centre for Synthetic Biology and Department of Bioengineering at Imperial College London, said: "By constructing a redesigned chromosome from telomere to telomere, and showing it can replace a natural chromosome just fine, our team's work establishes the foundations for designing and making synthetic chromosomes and even genomes for complex organisms like plants and animals."

As well as the leads of Nottingham and Imperial College London, the UK team also includes scientists from the universities of Edinburgh, Cambridge, and Manchester in the UK, as well as John Hopkins University and New York University Langone Health in the USA and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Querétaro in Mexico.

The work was funded by the BBSRC.

END

Scientists take major step towards completing the world’s first synthetic yeast.

2023-11-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New antifungal molecule kills fungi without toxicity in human cells, mice

2023-11-08

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new antifungal molecule, devised by tweaking the structure of prominent antifungal drug Amphotericin B, has the potential to harness the drug’s power against fungal infections while doing away with its toxicity, researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and collaborators at the University of Wisconsin-Madison report in the journal Nature.

Amphotericin B, a naturally occurring small molecule produced by bacteria, is a drug used as a last resort to treat fungal infections. While AmB excels at killing fungi, it is reserved ...

Cellular “atlas” built to guide precision medicine treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

2023-11-08

Research consortium investigators analyzed over 314,000 cells from rheumatoid arthritis tissue, defining six types of inflammation involving diverse cell types and disease pathways

Understanding the disease at single-cell level may advance targeted drug development and treatment strategies

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation that leads to pain, joint damage, and disability, which affects approximately 18 million people worldwide. While RA therapies targeted to specific inflammatory pathways have emerged, only some patients’ symptoms improve with treatment, emphasizing the need for multiple ...

Estimated effectiveness of co-administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine with influenza vaccine

2023-11-08

About The Study: In this study that included 3.4 million adults, co-administration of the BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) and seasonal influenza vaccine was associated with generally similar effectiveness in the community setting against COVID-19–related and seasonal influenza vaccine-related outcomes compared with giving each vaccine alone and may help improve uptake of both vaccines.

Authors: Leah J. McGrath, Ph.D., of Pfizer Inc., in New York, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Age at diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and incident dementia

2023-11-08

About The Study: Earlier onset of atrial fibrillation was associated with an elevated risk of subsequent all-cause dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia in this study including 433,000 UK Biobank participants, highlighting the importance of monitoring cognitive function among patients with atrial fibrillation, especially those younger than 65 years at diagnosis.

Authors: Fanfan Zheng, Ph.D., of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College in Beijing, and Wuxiang Xie, Ph.D., of the Peking University First ...

Physicists trap electrons in a 3D crystal for the first time

2023-11-08

Electrons move through a conducting material like commuters at the height of Manhattan rush hour. The charged particles may jostle and bump against each other, but for the most part they’re unconcerned with other electrons as they hurtle forward, each with their own energy.

But when a material’s electrons are trapped together, they can settle into the exact same energy state and start to behave as one. This collective, zombie-like state is what’s known in physics as an electronic “flat band,” and scientists predict that when electrons are in this state they can start to ...

Scaling up nano for sustainable manufacturing

2023-11-08

A new self-assembling nanosheet could radically accelerate the development of functional and sustainable nanomaterials for electronics, energy storage, health and safety, and more.

Developed by a team led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the new self-assembling nanosheet could significantly extend the shelf life of consumer products. And because the new material is recyclable, it could also enable a sustainable manufacturing approach that keeps single-use packaging and electronics out of landfills.

The ...

Validating the role of inhibitory interneurons in memory

2023-11-08

Memory, a fundamental tool for our survival, is closely linked with how we encode, recall, and respond to external stimuli. Over the past decade, extensive research has focused on memory-encoding cells, known as engram cells, and their synaptic connections. Most of this research has centered on excitatory neurons and the neurotransmitter glutamate, emphasizing their interaction between specific brain regions.

To expand the understanding of memory, a research team led by KAANG Bong-Kiun (Seoul National University, Institute ...

Scientists tame biological trigger of deadly Huntington’s disease

2023-11-08

Huntington’s disease causes involuntary movements and dementia, has no cure, and is fatal. For the first time, UC Riverside scientists have shown they can slow its progression in flies and worms, opening the door to human treatments.

Key to understanding these advancements is the way that genetic information in cells is converted from DNA into RNA, and then into proteins. DNA is composed of chemicals called nucleotides: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). The order of these nucleotides determines what biological instructions are contained in a strand of DNA.

On occasion, some DNA nucleotides repeat themselves, ...

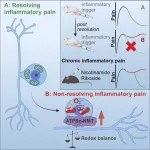

Disturbances in sensory neurons may alter transient pain into chronic pain

2023-11-08

Utrecht, November 8, 2023 - Researchers from the Center for Translational Immunology at University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands) have identified that a transient inflammatory pain causes mitochondrial and redox changes in sensory neurons that persist beyond pain resolution. These changes appear to predispose to a failure in resolution of pain caused by a subsequent inflammation. Additionally, targeting the cellular redox balance prevents and treats chronic inflammatory pain in rodents.

Pain often persists in patients with an ...

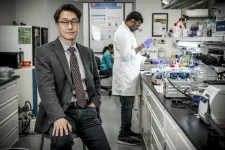

SMU Lyle nanorobotics professor awarded prestigious research grant to make gene therapy safer

2023-11-08

DALLAS (SMU) – SMU nanotechnology expert MinJun Kim and his team have been awarded a $1.8 million, R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for research related to gene therapy – a technique that modifies a person’s genes to treat or cure disease.

NIH R01 (Research Program) grants are extremely competitive, with fewer than 10 percent of applicants receiving one.

The four-year grant will allow Kim, the Robert C. Womack Chair in the Lyle School of Engineering at SMU (Southern Methodist University) and principal investigator ...