(Press-News.org) Making decisions is hard. Even when we know what we want, our choice often leaves something else on the table. For a hungry mouse, every morsel counts. But what if the decision is more consequential than choosing between crumbs and cheese?

Stanford researchers investigated how mice resolve conflicts between basic needs in a study published in Nature on Nov. 8. They presented mice that were both hungry and thirsty with equal access to food and water and watched to see what happened next.

The behavior of the mice surprised the scientists. Some gravitated first toward water, while others chose food. Then, with seemingly “random” periods of indulgence, they switched back and forth. In their study, PhD candidate Ethan Richman, lead author of the paper, and colleagues in the departments of Biology, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Bioengineering explored why. This work builds on years of collaboration between co-senior authors Karl Deisseroth, the D.H. Chen Professor at Stanford Medicine, and Liqun Luo, the Ann and Bill Swindells Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, to understand how the brain keeps the body alive.

Buridan’s what?

“There’s this old philosophical quandary called Buridan’s Ass,” explained Richman, “where you have a donkey that is equally hungry and thirsty and equally far from food and water.” The concept was posited by philosophers Aristotle, Jean Buridan, and Baruch Spinoza, in different forms. The question was whether the donkey would choose one need over the other or remain stubbornly in the middle.

But animals are constantly making choices. We must satisfy our needs to maintain homeostasis. Richman and colleagues wanted to know how the brain directs traffic through conflicting signals to flout Buridan. They call their behavioral experiment “Buridan’s Assay.”

If hunger or thirst directly motivated a mouse to eat or drink, it would switch as soon as one need outweighed the other. When needs were equal, the mouse would be stuck. This is not what the researchers observed. “Our data indicate that thirst and hunger don’t act as direct forces on behavior,” said Richman. “Instead, they modulate behavior more indirectly. They’re influencing what we think of as the current goal of the mouse.”

A mouse’s goal

We often think of choices as a decisive moment. The researchers wanted to understand when and where choices between food and water originate in the brain. Using recent advances in recording technology, they monitored activity from individual neurons spread across the mouse brain.

To their surprise, neuron activity patterns throughout the brain predicted the mouse’s choice, even before it was presented with options. “Instead of a single moment of choice, the mouse’s brain is constantly broadcasting its current goal,” said Richman. “Outcomes of the hardest choices you make – when options are closely balanced in importance, but the categories are fundamentally different – may have to do with the state your brain happened to be in, even before the choice was presented,” said Deisseroth. “That’s an interesting outcome and it helps us understand aspects of human behavior better.”

Exploring the random

The researchers found that hungry and thirsty mice often make the same choice repeatedly before suddenly switching. “In eating mode, the mouse will just eat and eat. In drinking mode, it will drink and drink,” said Luo. “But there is an aspect of randomness that causes them to switch between these two. That way, in the long run, they fulfill both needs, even if at any given time they are only choosing one.”

To test this apparent randomness, the researchers ran another experiment, this time with hungry mice. As the mice ate, scientists introduced thirst through a technique called optogenetics. With optogenetics, they used light to activate neurons causing thirst. Sometimes the mice switched to water, and sometimes they ignored it and kept eating. The level of thirst was the same each time, leading the researchers to conclude there is a key randomness influencing the mouse’s goal.

The scientists were perplexed by the interplay between this randomness and the relative intensities of hunger and thirst. To better understand it, they turned to mathematical modeling. Inspired by a conceptual resemblance between their results and a distant field of physics, the researchers borrowed, tweaked, and simulated several equations.

“We were extremely surprised and excited to find that a few simple equations from a seemingly unrelated discipline could closely predict aspects of mouse behavior and brain activity,” said Richman. The results of their modeling suggested that the brain activity relating to the mouse’s goal is constantly in motion. It gets trapped by needs like hunger and thirst. To escape and transition from one goal to another, the mouse relies on a lucky series of random activity.

This work establishes the importance of the brain’s shifting baseline state when it comes to decision-making. In the future, the researchers will explore what sets the tone and why decisions don’t always make sense.

Beyond Buridan

“In terms of Buridan’s Ass, we can say that the donkey’s mind is made up before it is given a choice,” says Richman, “and if it has to wait, then its choice may spontaneously switch.” Clinical applications for this work in the human context are a bit more complex. “As a psychiatrist, I often think about how we make healthy (adaptive) or harmful (maladaptive) decisions,” said Deisseroth. (Maladaptive behaviors impact people’s ability to make decisions in their best interest and they are common in psychiatric disorders.) “It’s very hard for family and friends to see loved ones act against their own survival drives. It may help to understand the choices made as reflecting the underlying dynamical landscape of the patient’s brain, affected by the disorder more than by the patient’s conscious volition.”

Although this work might not explain human behavior, it begins to reveal an important framework for decision-making. “This is basic discovery science that depends on pretty advanced neuro-engineering, but at the core we address universal questions that people think about and experience all the time,” said Deisseroth. “It’s exciting to develop and apply modern tools to address these very old, deep, and personal questions.”

Additional Stanford co-authors include former undergraduate student Nicole Ticea, BS ’20, who is now a PhD student at Stanford, and former graduate student William E. Allen, PhD ’19, who is now at Harvard University. Deisseroth is also professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Luo is also a professor of biology, a faculty fellow at Sarafan ChEM-H, and a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Deisseroth and Luo are both are investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Gatsby Foundation.

END

How mice choose to eat or to drink

2023-11-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Plant lifecycle insights: Big data can predict climate change impact

2023-11-08

The study is based on a new database created by the researchers which combines, for the first time, datasets on distribution and datasets on lifecycles, making it possible to establish the prevalence of different lifecycles around the globe. It uses empirical tools and big data to examine theoretical paradigms about the way in which human disturbance is affecting annual plants and their global distribution. Among other things, it was found that annuals are expected to benefit more with the rise in human population density and due to climate change, which ...

Scientists one step closer to re-writing world’s first synthetic yeast genome, unravelling the fundamental building blocks of life

2023-11-08

Scientists have engineered a chromosome entirely from scratch that will contribute to the production of the world’s first synthetic yeast.

Researchers in the Manchester Institute of Biotechnology (MIB) at The University of Manchester have created the tRNA Neochromosome – a chromosome that is new to nature.

It forms part of a wider project (Sc2.0) that has now successfully synthesised all 16 native chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, common baker’s yeast, and aims to combine ...

Scientists take major step towards completing the world’s first synthetic yeast.

2023-11-08

A UK-based team of Scientists, led by experts from the University of Nottingham and Imperial College London, have completed construction of a synthetic chromosome as part of a major international project to build the world’s first synthetic yeast genome.

The work, which is published in Cell Genomics, represents completion of one of the 16 chromosomes of the yeast genome by the UK team, which is part of the biggest project ever in synthetic biology; the international synthetic yeast genome collaboration.

The collaboration, known as 'Sc2.0' has been a 15-year project involving teams from around the world (UK, US, China, Singapore, UK, France and Australia), working together ...

New antifungal molecule kills fungi without toxicity in human cells, mice

2023-11-08

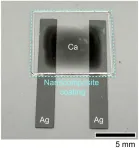

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new antifungal molecule, devised by tweaking the structure of prominent antifungal drug Amphotericin B, has the potential to harness the drug’s power against fungal infections while doing away with its toxicity, researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and collaborators at the University of Wisconsin-Madison report in the journal Nature.

Amphotericin B, a naturally occurring small molecule produced by bacteria, is a drug used as a last resort to treat fungal infections. While AmB excels at killing fungi, it is reserved ...

Cellular “atlas” built to guide precision medicine treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

2023-11-08

Research consortium investigators analyzed over 314,000 cells from rheumatoid arthritis tissue, defining six types of inflammation involving diverse cell types and disease pathways

Understanding the disease at single-cell level may advance targeted drug development and treatment strategies

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation that leads to pain, joint damage, and disability, which affects approximately 18 million people worldwide. While RA therapies targeted to specific inflammatory pathways have emerged, only some patients’ symptoms improve with treatment, emphasizing the need for multiple ...

Estimated effectiveness of co-administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine with influenza vaccine

2023-11-08

About The Study: In this study that included 3.4 million adults, co-administration of the BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) and seasonal influenza vaccine was associated with generally similar effectiveness in the community setting against COVID-19–related and seasonal influenza vaccine-related outcomes compared with giving each vaccine alone and may help improve uptake of both vaccines.

Authors: Leah J. McGrath, Ph.D., of Pfizer Inc., in New York, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Age at diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and incident dementia

2023-11-08

About The Study: Earlier onset of atrial fibrillation was associated with an elevated risk of subsequent all-cause dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia in this study including 433,000 UK Biobank participants, highlighting the importance of monitoring cognitive function among patients with atrial fibrillation, especially those younger than 65 years at diagnosis.

Authors: Fanfan Zheng, Ph.D., of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College in Beijing, and Wuxiang Xie, Ph.D., of the Peking University First ...

Physicists trap electrons in a 3D crystal for the first time

2023-11-08

Electrons move through a conducting material like commuters at the height of Manhattan rush hour. The charged particles may jostle and bump against each other, but for the most part they’re unconcerned with other electrons as they hurtle forward, each with their own energy.

But when a material’s electrons are trapped together, they can settle into the exact same energy state and start to behave as one. This collective, zombie-like state is what’s known in physics as an electronic “flat band,” and scientists predict that when electrons are in this state they can start to ...

Scaling up nano for sustainable manufacturing

2023-11-08

A new self-assembling nanosheet could radically accelerate the development of functional and sustainable nanomaterials for electronics, energy storage, health and safety, and more.

Developed by a team led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the new self-assembling nanosheet could significantly extend the shelf life of consumer products. And because the new material is recyclable, it could also enable a sustainable manufacturing approach that keeps single-use packaging and electronics out of landfills.

The ...

Validating the role of inhibitory interneurons in memory

2023-11-08

Memory, a fundamental tool for our survival, is closely linked with how we encode, recall, and respond to external stimuli. Over the past decade, extensive research has focused on memory-encoding cells, known as engram cells, and their synaptic connections. Most of this research has centered on excitatory neurons and the neurotransmitter glutamate, emphasizing their interaction between specific brain regions.

To expand the understanding of memory, a research team led by KAANG Bong-Kiun (Seoul National University, Institute ...