(Press-News.org) Soaring, wings outstretched, many birds sail through the air unhindered. However, species that dine on fruit, seeds and nectar must negotiate tiny gaps in cluttered foliage to secure a feast. To pass through apertures, many birds pull in their wings, folding them closer to their bodies. However, some of the most manoeuvrable aviators, hummingbirds, have lost the ability to fold their wings at the wrists and elbows. ‘Unless hummingbirds implement distinctive strategies to transit narrow apertures, they may be unable to enter gaps less than one wingspan wide’, says Marc Badger from University of California, Berkeley (UCB), USA. So how do the extraordinarily agile aeronauts, which can even fly backwards, negotiate the cluttered environments that make their homes? Teaming up with Kathryn McClain, Ashley Smiley, Jessica Ye and Robert Dudley (all from UCB), Badger set out to discover how Anna’s hummingbirds (Calypte anna) slip through tiny openings despite being unable to fold their wings in. The team publishes their discovery in Journal of Experimental Biology that they birds use two unique strategies that allow them to penetrate gaps that are barely half a wingspan wide.

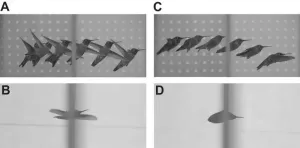

‘We set up a two-sided flight arena and wondered how to train birds to fly through a 16 cm2 gap in the partition separating the two sides. Then Kathryn had the amazing idea to use alternating rewards’, says Badger, explaining that the team only refilled a flower-shaped feeder with a sip of sugar solution once the bird had returned to the feeder opposite, to encourage the ~12 cm wingspan birds to flit to and fro. Badger, Smiley and Ye then replaced the gap with a series of smaller oval and circular apertures – ranging in height, width and diameter from 12 to 6 cm – for the birds to negotiate, while they filmed the birds’ manoeuvres with high-speed cameras. Then, Badger wrote a computer program to methodically track the position of each bird’s bill as they approached and passed through each aperture, while also locating the bird’s wing tips, to calculate their wing positions as they transited through.

Impressively, the hummingbirds used two unique strategies to negotiate the gaps. In the first, they approached the aperture, often hovering in front of it to assess it first, before travelling through sideways, reaching forward with one wing while sweeping the second wing back – almost making the shape of a cross – while still fluttering their wings to fly through the aperture, then swivelling forward to continue on their way. In the second strategy, they swept their wings back, pinning them to their bodies, and shot through beak first like a bullet, before sweeping the wings forward and resuming flapping again once safely through.

Scrutinising the two strategies, the team realised that the birds that were travelling sideways tended to fly more cautiously and slowly than the birds that shot through the apertures beak first. And, as the birds became more familiar with the apertures after several approaches, they appeared to become more confident, approaching swiftly and dropping the more cautious sideways approach in favour of darting through beak first. However, the smallest aperture – half a wingspan wide – always presented the most difficulty, with every bird zipping through facing forward with their wings pinned back – even on the first attempt – to avoid collisions.

So, hummingbirds have developed strategies that allow them to penetrate tiny gaps less than a wingspan wide, with the sideways option enabling them to take a more cautious approach, transitioning to shooting through beak first as they become bolder. And the team points out that although ~8% of the birds clipped their wings as they passed through the partition, only one experienced a major collision, and even then, the bird recovered quickly before successfully reattempting the manoeuvre and going on its way.

***********************

IF REPORTING THIS STORY, PLEASE MENTION JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY AS THE SOURCE AND, IF REPORTING ONLINE, PLEASE CARRY A LINK TO: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article-lookup/doi/10.1242/jeb.245643

REFERENCE: Badger, M., McClain, K., Smiley, A., Ye, J. and Dudley, R. (2023). Sideways maneuvers enable narrow aperture negotiation by free-flying hummingbirds. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb245643. doi:10.1242/jeb.245643

DOI: 10.1242/jeb.245643

Registered journalists can obtain a copy of the article under embargo from http://pr.biologists.com. Unregistered journalists can register at http://pr.biologists.com to access the embargoed content.

This article is posted on this site to give advance access to other authorised media who may wish to report on this story. Full attribution is required and if reporting online a link to https://journals.biologists.com/jeb is also required. The story posted here is COPYRIGHTED. Advance permission is required before any and every reproduction of each article in full from permissions@biologists.com.

END

Most birds that flit through dense, leafy forests have a strategy for maneuvering through tight windows in the vegetation — they bend their wings at the wrist or elbow and barrel through.

But hummingbirds can't bend their wing bones during flight, so how do they transit the gaps between leaves and tangled branches?

A study published today in the Journal of Experimental Biology shows that hummingbirds have evolved their own unique strategies — two of them, in fact. These strategies have not been reported before, likely because hummers maneuver too ...

New survey data from the 7th National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists (NAP7) published in Anaesthesia (the journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) shows that potentially serious complications occur in one in 18 procedures under the care of an anaesthetist.

The risk factors associated with these potentially serious complications include very young age (babies); comorbidities; being male; increased frailty; the urgency and extent of surgery; and surgery taking place at night and/or at weekends.

This paper has been produced by a team of authors across ...

Laser epilation, commonly known as laser hair removal, reduced the risk of recurrence in patients with pilonidal disease, an inflammatory, painful, and sometimes chronic or recurring condition, according to research conducted by Peter C. Minneci, M.D., Chair of Surgery at Nemours Children’s Health, Delaware Valley, and published in JAMA Surgery.

Pilonidal disease occurs when cysts form between the buttocks. It is believed to be an inflammatory reaction to hair or debris that gets caught in the crease of the buttocks. The disease occurs in 26 to 100 per 100,000 people and is most common in adolescents and young ...

A new study examining the effects of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization on June 24, 2022, which overturned Roe v. Wade's constitutional protection of abortion rights, finds that the American public's support for abortion increased after the decision.

The findings were published today in Nature Behaviour.

"Our results show the extent to which the Supreme Court is out of step with the American public," says co-author Sean Westwood, an associate professor of government at Dartmouth and director of the Polarization Research Lab.

The study's findings were based on a large, three-wave survey before the leak ...

The next time your friend displays remarkable openness to their opposite political camp’s ideas, you might try pinching them.

Okay, we don’t really recommend that. But new evidence shows that people with increased sensitivity to pain are also more likely to endorse values more common to people of their opposite political persuasion. It doesn’t stop there. They also show stronger support for the other camp’s politicians, and, get this -- more likely to vote for Donald Trump in 2020 if they are liberal, or Joe Biden if they are conservative.

Even ...

Critical Path Institute (C-Path) is pleased to announce the release of a new peer-reviewed publication, titled “Transforming Drug Development for Neurological Disorders: Proceedings from a Multi-disease Area Workshop,” now published in Neurotherapeutics, The Journal of the American Society for Experimental Neurotherapeutics.

A distinguished team of C-Path scientists and patient-advocates spearheaded by Diane Stephenson, Ph.D., C-Path’s Executive Director of the Critical Path for Parkinson’s Consortium (CPP), has presented its learnings from C-Path’s 2022 Neuroscience Program Annual Workshop. The publication can be accessed in its entirety here.

Neurological ...

Over the past decade, AI has permeated nearly every corner of science: Machine learning models have been used to predict protein structures, estimate the fraction of the Amazon rainforest that has been lost to deforestation and even classify faraway galaxies that might be home to exoplanets.

But while AI can be used to speed scientific discovery — helping researchers make predictions about phenomena that may be difficult or costly to study in the real world — it can also lead scientists astray. In the same way that chatbots sometimes “hallucinate,” ...

Lasers have become relatively commonplace in everyday life, but they have many uses outside of providing light shows at raves and scanning barcodes on groceries. Lasers are also of great importance in telecommunications and computing as well as biology, chemistry, and physics research.

In those latter applications, lasers that can emit extremely short pulses—those on the order of one-trillionth of a second (one picosecond) or shorter—are especially useful. Using lasers operating on such small timescales, researchers can study physical and chemical ...

An analysis of beeswax in managed honeybee hives in New York found a wide variety of pesticide, herbicide and fungicide residues – exposing current and future generations of bees to long-term toxicity.

The study, published in the Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, notes that people may be similarly exposed through contaminated honey, pollen and wax in cosmetics. Though the chemicals found in wax are not beneficial to humans, the small amounts in these products are unlikely to ...

Researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil, partnering with colleagues in Australia, have identified a novel bacterial protein that can keep human cells healthy even when the cells have a heavy bacterial burden. The discovery could lead to new treatments for a wide array of diseases relating to mitochondrial dysfunction, such as cancer and auto-immune disorders. Mitochondria are organelles that supply most of the chemical energy needed to power cells’ biochemical reactions.

An article on the study is published in the journal PNAS. The researchers ...