(Press-News.org) The majority of breast cancers start in the lining of a breast milk duct and, if they remain there, are very treatable. But once these cancers become invasive – breaking through a thin matrix around the duct, called the basement membrane, and spreading to the surrounding tissue – treatment becomes more challenging.

In a recent paper, published on Nov. 13 in Nature Materials, researchers at Stanford revealed a novel physical mechanism that breast cancer cells use to break out and become invasive. They found that, in addition to established chemical methods of degrading the basement membrane, cancer cells work as a group to physically deform and tear through the basement membrane barrier.

“When this invasion process has been studied, the focus has typically been on single cells,” said Ovijit Chaudhuri, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and bioengineering, by courtesy. “But what we know is that the invasion is actually collective in nature, involving groups of cells working together to penetrate through the basement membrane. Our work has elucidated how cells act together to break through the basement membrane, advancing our fundamental understanding of this critical transition in cancer progression.”

A model for mechanical forces

Previous research has shown that individual cancer cells can produce enzymes, called proteases, that break down some of the basement membrane, but treatments inhibiting proteases haven’t been able to stop cancer cells from breaking loose. Chaudhuri and his colleagues figured there must be other mechanisms at work, so they developed a new model to study breast cancer and the basement membrane in three dimensions.

“What we’re really looking at are the mechanical forces involved, which is a different perspective,” said Julie Chang, who conducted the work as a doctoral student in Chaudhuri’s lab and is one of the lead authors on the paper. “The current paradigm is that cells use chemicals to degrade through the basement membrane, but we show that this physical aspect is just as important.”

The researchers designed a 3D hydrogel that mimics the properties of breast tissue and cultured cellular structures, called acini, that exhibit features of a breast duct and are surrounded by their own basement membrane. They tagged the basement membrane with fluorescent markers so that they could see and measure any deformation as cancerous cells interacted with it. And what they saw surprised them.

The cancer cells trapped within the acini swelled together, causing the basement membrane to stretch like a balloon. This stretching process thinned and weakened the basement membrane, which allowed cancer cells near the membrane to apply additional forces to open holes and escape.

“The cells are expanding and increasing their volume in unison, and then locally pulling to tear up the basement membrane,” said Aashrith Saraswathibhatla, a postdoctoral researcher in Chaudhuri’s lab and co-lead author on the paper. “This collective volume expansion hasn’t been predicted before – no one was thinking about it.”

The researchers determined that key findings from their 3D model were consistent with what has been seen in patients with invasive breast cancers. They also consulted with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania who were able to validate their results with computational modeling, confirming the physical forces involved could theoretically allow cells to break through the basement membrane.

From new mechanisms to new treatments

Understanding how cancer cells act together and the mechanical forces they apply could lead to new therapeutic strategies to block invasion. It could also help researchers determine which patients with pre-invasive breast cancer are most likely to have their cancer break out and spread, which could result in more targeted treatments.

While this work is just the first step towards these possibilities, the researchers are continuing to make progress in this realm. They are investigating how cancerous cells physically interact with the surrounding breast tissue once they break through the basement membrane and diving deeper into understanding the basement membrane itself – looking into both mechanical and structural features – to get more insight into why some tumors become invasive and others don’t.

“This global volume expansion mechanism represents a new insight into how the breast tumors become invasive, borne out of the development of a 3D culture model that allowed us to visualize the invasion process,” Chaudhuri said. “It highlights the emergent behaviors arising in groups of cells acting together that enable cancer invasion.”

Chaudhuri is a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Cardiovascular Institute, and the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance; and a faculty fellow of Stanford Sarafan ChEM-H.

Additional Stanford co-authors of this research include Professor Robert B. West; associate professors Michael Bassik and M. Peter Marinkovich; research professionals Sushama Varma and Sucheta Srivastava; and graduate students Naomi Hassan Kahtan Alyafei, Dhiraj Indana, Raleigh Slyman, and Katherine Liu. Other co-authors are from University of Pennsylvania and Albert Einstein College of Medicine. This work was funded by Advancing Science in America, a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate fellowship, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of General Medicine, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the Office of Research and Development in the Palo Alto VA Medical Center.

END

Breast cancer cells collaborate to break free and invade into the surrounding tissue

2023-11-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ammonia for fertilisers without the giant carbon footprint

2023-11-14

The production of ammonia for fertilisers – which has one of the largest carbon footprints among industrial processes – will soon be possible on farms using low-cost, low-energy and environmentally friendly technology.

This is thanks to researchers at UNSW Sydney and their collaborators who have developed an innovative technique for sustainable ammonia production at scale.

Up until now, the production of ammonia has relied on high-energy processes that leave a massive global carbon footprint – temperatures of more ...

Some of today’s earthquakes may be aftershocks from quakes in the 1800s

2023-11-14

American Geophysical Union

13 November 2023

AGU Release No. 23-42

For Immediate Release

This press release and accompanying multimedia are available online at: https://news.agu.org/press-release/some-of-todays-earthquakes-may-be-aftershocks-from-quakes-in-the-1800s

Some of today’s earthquakes may be aftershocks from quakes in the 1800s

Aftershocks follow large earthquakes — sometimes for weeks, other times for decades. But in the U.S., some areas may be experiencing shocks from centuries-old events.

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, news@agu.org (UTC-5 hours)

Contact ...

Earth's surface water dives deep, transforming core's outer layer

2023-11-14

A few decades ago, seismologists imaging the deep planet identified a thin layer, just over a few hundred kilometers thick. The origin of this layer, known as the E prime layer, has been a mystery — until now.

An international team of researchers, including Arizona State University scientists Dan Shim, Taehyun Kim and Joseph O’Rourke of the School of Earth and Space Exploration, has revealed that water from the Earth's surface can penetrate deep into the planet, altering the composition of the outermost region of the metallic liquid core and creating a distinct, thin layer. Illustration of silica crystals coming out from the liquid metal of ...

Faster Arctic warming hastens 2C rise by eight years

2023-11-14

Faster warming in the Arctic will be responsible for a global 2C temperature rise being reached eight years earlier than if the region was warming at the average global rate, according to a new modelling study led by UCL researchers.

The Arctic is currently warming nearly four times faster than the global average rate. The new study, published in the journal Earth System Dynamics, aimed to estimate the impact of this faster warming on how quickly the global temperature thresholds of 1.5C and 2C, set down in the Paris Agreement, are likely to be breached.

To do this, the research team created alternative ...

New 'library of greening' can help poorest urban communities the most, Surrey expert says

2023-11-14

Surrey scientists are celebrating with colleagues around the world, after winning new funding for a ‘library of greening’ – a new database enabling towns and cities to learn from each other's success developing green spaces, waterways and other sustainability initiatives.

The RECLAIM Network Plus provides a one-stop-shop for towns and cities looking to mitigate the impacts of climate change and improve their resilience. It has over 500 members worldwide, offering information and support to implement projects such as ...

New antiphospholipid syndrome research findings presented at ACR Convergence 2023

2023-11-14

Investigators from the Antiphospholipid Syndrome Alliance for Clinical Trials and International Networking (APS ACTION) presented new research findings in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence 2023, the ACR’s annual meeting.

Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS), one of the leading centers in the United States providing care for adults and children with APS, is the lead coordinating center for APS ACTION, an international research network of 34 academic institutions dedicated to advancing the understanding and management of APS. APS ACTION conducts large, ...

UTA developing more powerful rocket engines for space travel

2023-11-14

A University of Texas at Arlington engineering researcher has received a NASA grant to use rotating detonation rocket engines (RDREs) for in-space propulsion to make them more efficient, compact and powerful.

Liwei Zhang, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE), will lead the $900,000 grant.

“Detonation is very fast combustion. Inside an RDRE, detonation waves spin around in a circle at supersonic speeds. Compared to conventional engines that rely on regular combustion, an RDRE has a theoretically ...

A how-to for reducing flooding impacts in coastal towns

2023-11-14

A University of Texas at Arlington civil engineering researcher is determining what strategies are most effective at lessening flooding in coastal communities.

Michelle Hummel, a civil engineering assistant professor, is using a $499,973 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant to study the benefits and costs of flood-reduction strategies aimed at increasing coastal resilience to storms and sea-level rise.

Hummel and her colleague, Kevin Befus of the University of Arkansas, will apply advanced ...

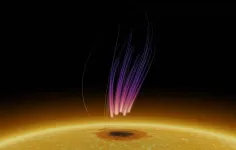

NJIT scientists uncover aurora-like radio emission above a sunspot

2023-11-13

In a study published in Nature Astronomy, astronomers from New Jersey Institute of Technology’s Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research (NJIT-CSTR) have detailed radio observations of an extraordinary aurora-like display — occurring 40,000 km above a relatively dark and cold patch on the Sun, known as a sunspot.

Researchers say the novel radio emission shares characteristics with the auroral radio emissions commonly seen in planetary magnetospheres such as those around Earth, Jupiter and Saturn, as well as certain low-mass stars.

The discovery offers new insights into the origin of such intense solar radio bursts and potentially opens new avenues ...

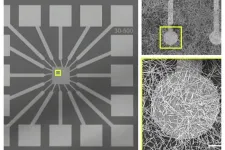

Experimental brain-like computing system more accurate with custom algorithm

2023-11-13

FINDINGS

An experimental computing system physically modeled after the biological brain “learned” to identify handwritten numbers with an overall accuracy of 93.4%. The key innovation in the experiment was a new training algorithm that gave the system continuous information about its success at the task in real time while it learned.

The algorithm outperformed a conventional machine-learning approach in which training was performed after a batch of data has been processed, producing 91.4% accuracy. The researchers also showed that memory of past inputs stored in the system itself enhanced learning. In contrast, other ...