(Press-News.org)

New research published today in leading international journal Science Advances paints an uncharacteristically upbeat picture for the planet. This is because more realistic ecological modelling suggests the world’s plants may be able to take up more atmospheric CO2 from human activities than previously predicted.

Despite this headline finding, the environmental scientists behind the research are quick to underline that this should in no way be taken to mean the world’s governments can take their foot off the brake in their obligations to reduce carbon emissions as fast as possible. Simply planting more trees and protecting existing vegetation is not a golden-bullet solution but the research does underline the multiple benefits to conserving such vegetation.

“Plants take up a substantial amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) every year, thereby slowing down the detrimental effects of climate change, but the extent to which they will continue this CO2 uptake into the future has been uncertain,” explains Dr Jürgen Knauer, who headed the research team led by the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University.

“What we found is that a well-established climate model that is used to feed into global climate predictions made by the likes of the IPCC predicts stronger and sustained carbon uptake until the end of the 21st century when it accounts for the impact of some critical physiological processes that govern how plants conduct photosynthesis.

“We accounted for aspects like how efficiently carbon dioxide can move through the interior of the leaf, how plants adjust to changes in temperatures, and how plants most economically distribute nutrients in their canopy. These are three really important mechanisms that affect a plant’s ability to ‘fix’ carbon, yet they are commonly ignored in most global models” said Dr Knauer.

Photosynthesis is the scientific term for the process in which plants convert – or “fix” – CO2 into the sugars they use for growth and metabolism. This carbon fixing serves as a natural climate change mitigator by reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere; it is this increased uptake of CO2 by vegetation that is the primary driver of an increasing land carbon sink reported over the last few decades.

However, the beneficial effect of climate change on vegetation carbon uptake might not last forever and it has long been unclear how vegetation will respond to CO2, temperature and changes in rainfall that are significantly different from what is observed today. Scientists have thought that intense climate change such as more intense droughts and severe heat could significantly weaken the sink capacity of terrestrial ecosystems, for example.

In the study published this week, however, Knauer and colleagues present results from their modelling study set to assess a high-emission climate scenario, to test how vegetation carbon uptake would respond to global climate change until the end of the 21st century.

The authors tested different versions of the model that varied in their complexity and realism of how plant physiological processes are accounted for. The simplest version ignored the three critical physiological mechanisms associated with photosynthesis while the most complex version accounted for all three mechanisms.

The results were clear: the more complex models that incorporated more of our current plant physiological understanding consistently projected stronger increases of vegetation carbon uptake globally. The processes accounted for re-enforced each other, so that effects were even stronger when accounted for in combination, which is what would happen in a real-world scenario.

Silvia Caldararu, Assistant Professor in Trinity’s School of Natural Sciences, was involved in the study. Contextualising the findings and their relevance, she said:

“Because the majority of terrestrial biosphere models used to assess the global carbon sink are located at the lower end of this complexity range, accounting only partially for these mechanisms or ignoring them altogether, it is likely that we are currently underestimating climate change effects on vegetation as well as its resilience to changes in climate. We often think about climate models as being all about physics, but biology plays a huge role and it is something that we really need to account for.

“These kinds of predictions have implications for nature-based solutions to climate change such as reforestation and afforestation and how much carbon such initiatives can take up. Our findings suggest these approaches could have a larger impact in mitigating climate change and over a longer time period than we thought.

“However, simply planting trees will not solve all our problems. We absolutely need to cut down emissions from all sectors. Trees alone cannot offer humanity a get out of jail free card.”

END

EL PASO, Texas (Nov. 17, 2023) – Could the solution to the decades-long battle against malaria be as simple as soap? In a new study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, scientists at The University of Texas at El Paso have made a compelling case for it.

The team has found that adding small quantities of liquid soap to some classes of pesticides can boost their potency by more than ten-fold.

The discovery is promising news as malaria-carrying mosquitoes display ...

Using historical records from around Australia, an international team of researchers have put forward the most accurate prediction to date of past Antarctic ice sheet melt, providing a more realistic forecast of future sea level rise.

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest block of ice on earth, containing over 30 million cubic kilometers of water.

Hence, its melting could have a devasting impact on future sea levels. To find out just how big that impact might be, the research team, including Dr Mark Hoggard from The Australian National University, turned to the past.

“If ...

Policies that encourage landlords to evict tenants who have involvement with the criminal justice system do not appear to reduce crime, while increasing evictions among Black residents and people with lower incomes, according to a new RAND Corporation report.

Studying “crime-free housing policies” adopted by cities in California over a decade-long period, researchers found no meaningful statistical evidence that the policies reduce crime.

The study also found that crime-free housing policies significantly increased ...

This year’s European Antibiotic Awareness Day (EAAD) focuses on the targets outlined in the 2023 Council Recommendation to step up efforts in the European Union (EU) against antimicrobial resistance in a One Health approach. [1] Those recommendations formulate the 2023 goal to reduce total antibiotic consumption (community and hospital sectors combined) by 20%, using consumption data from 2019 as baseline.

Consumption of antibiotics in the community accounts for around 90% of the total use. This means, that a substantial and consistent decline in the use of antibiotics in this sector will be key on the way towards reaching ...

New Orleans, LA – The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Foundation has selected Rahn Baily, MD, DLFAPA, ACP, Professor and Chair of Psychiatry at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine, as the recipient of the 2024 Solomon Carter Fuller Award.

According to the APA Foundation, “The Solomon Carter Fuller Award—established in 1969 and named for Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, recognized as the first Black psychiatrist in America—honors a Black citizen who has pioneered in ...

A team of scientists from the Institut Pasteur has used the database of the National Reference Center for Meningococci to trace the evolution of invasive meningococcal disease cases in France between 2015 and 2022, revealing an unprecedented resurgence in the disease after the easing of control measures imposed during the COVID-19 epidemic. Recently reported cases have mainly been caused by meningococcal serogroups that were less frequent before the pandemic, and there has been a particular uptick in cases among people aged 16 to 24. The results, published in the Journal of Infection and Public Health on October 12, ...

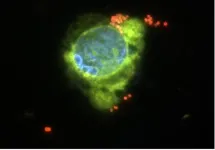

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have identified a protein key to the development of a type of brain cell believed to play a role in disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and used the discovery to grow the neurons from stem cells for the first time.

The stem-cell-derived norepinephrine neurons of the type found in a part of the human brain called the locus coeruleus may enable research into many psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases and provide a tool for developing ...

Migraine is more than just a headache. Often the pain is accompanied by nausea, vomiting, light sensitivity, and sound sensitivity. Chronic migraine can be disabling and may prevent many, especially women, from contributing to working life.

Still, it often takes a long time for migraine patients to find a treatment that works well for them. Researchers at the Norwegian Center for Headache Research (NorHead) have used data from the Norwegian Prescription Register to look at which medicines best prevent migraine in people in Norway:

“There has now been done a lot of research on this subject ...

University of B.C. researchers have uncovered startling connections between micronutrient deficiencies and the composition of gut microbiomes in early life that could help explain why resistance to antibiotics has been rising across the globe.

The team investigated how deficiencies in crucial micronutrients such as vitamin A, B12, folate, iron, and zinc affected the community of bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microbes that live in the digestive system.

They discovered that these deficiencies led to significant shifts in the gut ...

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and KU Leuven have discovered a suite of genes that influence head shape in humans. These findings, published this week in Nature Communications, help explain the diversity of human head shapes and may also offer important clues about the genetic basis of conditions that affect the skull, such as craniosynostosis.

By analyzing measurements of the cranial vault — the part of the skull that forms the rounded top of the head and protects the brain — the team identified 30 regions of the genome associated with different aspects of head shape, 29 of which have not been reported previously.

“Anthropologists ...