(Press-News.org) Blame it on plate tectonics. The deep ocean is never preserved, but instead is lost to time as the seafloor is subducted. Geologists are mostly left with shallower rocks from closer to the shoreline to inform their studies of Earth history.

“We have only a good record of the deep ocean for the last ~180 million years,” said David Fike, the Glassberg/Greensfelder Distinguished University Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “Everything else is just shallow-water deposits. So it’s really important to understand the bias that might be present when we look at shallow-water deposits.”

One of the ways that scientists like Fike use deposits from the seafloor is to reconstruct timelines of past ecological and environmental change. Researchers are keenly interested in how and when oxygen began to build up in the oceans and atmosphere, making Earth more hospitable to life as we know it.

For decades they have relied on pyrite, the iron-sulfide mineral known as “fool’s gold,” as a sensitive recorder of conditions in the marine environment where it is formed. By measuring the bulk isotopic composition of sulfur in pyrite samples — the relative abundance of sulfur atoms with slightly different mass — scientists have tried to better understand ancient microbial activity and interpret global chemical cycles.

But the outlook for pyrite is not so shiny anymore. In a pair of companion papers published Nov. 24 in the journal Science, Fike and his collaborators show that variations in pyrite sulfur isotopes may not represent the global processes that have made them such popular targets of analysis.

Instead, Fike’s research demonstrates that pyrite responds predominantly to local processes that should not be taken as representative of the whole ocean. A new microanalysis approach developed at Washington University helped the researchers to separate out signals in pyrite that reveal the relative influence of microbes and that of local climate.

For the first study, Fike worked with Roger Bryant, who completed his graduate studies at Washington University, to examine the grain-level distribution of pyrite sulfur isotope compositions in a sample of recent glacial-interglacial sediments. They developed and used a cutting-edge analytical technique with the secondary-ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) in Fike’s laboratory.

“We analyzed every individual pyrite crystal that we could find and got isotopic values for each one,” Fike said. By considering the distribution of results from individual grains, rather than the average (or bulk) results, the scientists showed that it is possible to tease apart the role of the physical properties of the depositional environment, like the sedimentation rate and the porosity of the sediments, from the microbial activity in the seabed.

“We found that even when bulk pyrite sulfur isotopes changed a lot between glacials and interglacials, the minima of our single grain pyrite distributions remained broadly constant,” Bryant said. “This told us that microbial activity did not drive the changes in bulk pyrite sulfur isotopes and refuted one of our major hypotheses.”

“Using this framework, we’re able to go in and look at the separate roles of microbes and sediments in driving the signals,” Fike said. “That to me represents a huge step forward in being able to interpret what is recorded in these signals.”

In the second paper, led by Itay Halevy of the Weizmann Institute of Science and co-authored by Fike and Bryant, the scientists developed and explored a computer model of marine sediments, complete with mathematical representations of the microorganisms that degrade organic matter and turn sulfate into sulfide and the processes that trap that sulfide in pyrite.

“We found that variations in the isotopic composition of pyrite are mostly a function of the depositional environment in which the pyrite formed,” Halevy said. The new model shows that a range of parameters of the sedimentary environment affect the balance between sulfate and sulfide consumption and resupply, and that this balance is the major determinant of the sulfur isotope composition of pyrite.

“The rate of sediment deposition on the seafloor, the proportion of organic matter in that sediment, the proportion of reactive iron particles, the density of packing of the sediment as it settles to the seafloor — all of these properties affect the isotopic composition of pyrite in ways that we can now understand,” he said.

Importantly, none of these properties of the sedimentary environment are strongly linked to the global sulfur cycle, to the oxidation state of the global ocean, or essentially any other property that researchers have traditionally used pyrite sulfur isotopes to reconstruct, the scientists said.

“The really exciting aspect of this new work is that it gives us a predictive model for how we think other pyrite records should behave,” Fike said. “For example, if we can interpret other records — and better understand that they are driven by things like local changes in sedimentation, rather than global parameters about ocean oxygen state or microbial activity — then we can try to use this data to refine our understanding of sea level change in the past.”

END

Separating out signals recorded at the seafloor

2023-11-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Dolomite crystals require cycles of saturation conditions to grow

2023-11-23

Addressing the long-standing “dolomite problem,” an oddity that has vexed scientists for nearly 200 years, researchers report that dolomite crystals require cycling of saturation conditions to grow. The findings provide new insights into how dolomite is formed and why modern dolomite is primarily found in natural environments with pH or salinity fluctuations. Dolomite – a calcium magnesium carbonate – is one of the major minerals in carbonate rocks, accounting for nearly 30% of the sedimentary carbonate minerality in Earth’s crust. However, despite its geological abundance, dolomite does not readily grow under laboratory conditions, ...

FLSHclust, a new algorithm, reveals rare and previously unknown CRISPR-Cas systems

2023-11-23

Using a new algorithm called FLSHclust (“flash clust”), researchers have discovered 188 rare and previously unknown CRISPR-linked gene modules – including a novel type VII CRISPR-Cas system – among billions of protein sequences. The approach and its findings provide novel opportunities for harnessing CRISPR systems and understanding the vast functional diversity of microbial proteins. CRISPR systems have been leveraged to develop a growing suite of novel biomolecular approaches, including CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing. The discovery ...

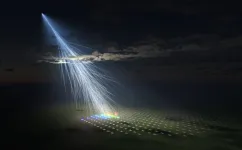

Extremely energetic cosmic ray detected, but with no obvious source

2023-11-23

An extremely energetic cosmic ray – an extragalactic particle with an energy exceeding ~240 exa-electron volts (EeV) – has been detected by the Telescope Array experiment’s surface detector, researchers report. However, according to the findings, its arrival direction shows no obvious source. Ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) are subatomic charged particles from space with energies greater than 1 EeV – roughly a million times as high as the energy reached by human-made particle accelerators. Although low-energy cosmic rays primarily emanate from the sun, the origins of rarer UHECRs are thought to be related to the most energetic phenomena in the Universe, ...

Telescope Array detects second highest-energy cosmic ray ever

2023-11-23

In 1991, the University of Utah Fly’s Eye experiment detected the highest-energy cosmic ray ever observed. Later dubbed the Oh-My-God particle, the cosmic ray’s energy shocked astrophysicists. Nothing in our galaxy had the power to produce it, and the particle had more energy than was theoretically possible for cosmic rays traveling to Earth from other galaxies. Simply put, the particle should not exist.

The Telescope Array has since observed more than 30 ultra-high-energy cosmic rays, though none approaching the Oh-My-God-level energy. No observations have yet revealed ...

'Dolomite Problem': 200-year-old geology mystery resolved

2023-11-23

Images // Video

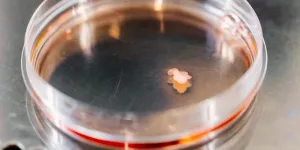

ANN ARBOR—For 200 years, scientists have failed to grow a common mineral in the laboratory under the conditions believed to have formed it naturally. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Michigan and Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan have finally pulled it off, thanks to a new theory developed from atomic simulations.

Their success resolves a long-standing geology mystery called the "Dolomite Problem." Dolomite—a key mineral in the Dolomite mountains in Italy, Niagara Falls, the White Cliffs of Dover and Utah's Hoodoos—is very abundant in rocks older than 100 million years, but nearly absent in younger ...

AI recognizes the tempo and stages of embryonic development

2023-11-23

Animal embryos go through a series of characteristic developmental stages on their journey from a fertilized egg cell to a functional organism. This biological process is largely genetically controlled and follows a similar pattern across different animal species. Yet, there are differences in the details – between individual species and even among embryos of the same species. For example, the tempo at which individual embryonic stages are passed through can vary. Such variations in embryonic development are considered an important driver of evolution, as they can lead to new characteristics, thus promoting evolutionary adaptations and biodiversity.

Studying the embryonic ...

Potential new target and drug candidate for Barth syndrome

2023-11-23

In a Nature Metabolism paper published today, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh detail a potential new target and a small-molecule drug candidate for treating Barth syndrome, a rare, life-threatening and currently incurable genetic disease with devastating consequences.

Barth syndrome affects about 1 in every 300,000 to 400,000 babies born worldwide. Those with the condition have weak muscles and hearts and experience debilitating fatigue and recurrent infections.

Pitt researchers discovered that faulty mitochondria are at least partially to blame, and identified a molecular culprit that could be targeted to potentially reverse the disease course in the future.

In ...

New therapy can treat rare and hereditary diseases

2023-11-23

A lot of research has been done over many decades on diseases that are widespread in large parts of the population, such as cancer and heart disease. As a result, treatment methods have improved enormously thanks to long-term research efforts on diseases that affect many people.

However, there are many diseases that affect just a handful people. These diseases often fly under the radar and are far less researched. They include quite a few rare, hereditary diseases, such as DOOR syndrome, which is ...

Y-chromosome and its impact on digestive diseases

2023-11-23

A major breakthrough in human genetics has been achieved with the complete decoding of the human Y chromosome, opening up new avenues for research into digestive diseases. This milestone, along with advancements in third-generation sequencing technologies, is poised to revolutionize our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of digestive disorders and pave the way for more personalized and effective treatment strategies.

The Y chromosome, the smallest of the human chromosomes, has long been shrouded in mystery due to its complex repetitive structure. However, recent advancements in sequencing technologies have enabled researchers to unravel the intricate details of this genetic ...

Fractional COVID-19 booster vaccines produce similar immune response as full-doses

2023-11-23

Reducing the dose of a widely used COVID-19 booster vaccine produces a similar immune response in adults to a full-dose with fewer side effects, according to a new study.

The research, led by Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and the National Centre for Communicable Diseases in Mongolia, found that a half dose of a Pfizer COVID-19 booster vaccine elicited a non-inferior immune response to a full dose in Mongolian adults who previously had AstraZeneca or Sinopharm COVID-19 shots. But it found half-dose boosting may be less effective in adults primed with the Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine.

The research ...