(Press-News.org) The evolution of higher cognitive functions in human beings has so far mostly been linked to the expansion of the neocortex – a region of the brain that is responsible, inter alia, for conscious thought, movement and sensory perception. Researchers are increasingly realising, however, that the “little brain” or cerebellum also expanded during evolution and probably contributes to the capacities unique to humans, explains Prof. Dr Henrik Kaessmann from the Center for Molecular Biology of Heidelberg University. His research team has – together with Prof. Dr Stefan Pfister from the Hopp Children’s Cancer Center Heidelberg – generated comprehensive genetic maps of the development of cells in the cerebella of human, mouse and opossum. Comparisons of these data reveal both ancestral and species-specific cellular and molecular characteristics of cerebellum development spanning over 160 million years of mammalian evolution.

“Although the cerebellum, a structure at the back of the skull, contains about 80 percent of all neurons in the whole human brain, this was long considered a brain region with a rather simple cellular architecture,” explains Prof. Kaessmann. In recent times, however, evidence suggesting a pronounced heterogeneity within this structure has been growing, says the molecular biologist. The Heidelberg researchers have now systematically classified all cell types in the developing cerebellum of human, mouse and opossum. To do so they first collected molecular profiles from almost 400,000 individual cells using single-cell sequencing technologies. They also employed procedures enabling spatial mapping of the cell types.

On the basis of these data the scientists noted that in the human cerebellum the proportion of Purkinje cells – large, complex neurons with key functions in the cerebellum – is almost double that of mouse and opossum in the early stages of foetal development. This increase is primarily driven by specific subtypes of Purkinje cells that are generated first during development and likely communicate with neocortical areas involved in cognitive functions in the mature brain. “It stands to reason that the expansion of these specific types of Purkinje cells during human evolution supports higher cognitive functions in humans,” explains Dr Mari Sepp, a postdoctoral researcher in Prof. Kaessmann’s research group “Functional evolution of mammalian genomes”.

Using bioinformatic approaches, the researchers also compared the gene expression programmes in cerebellum cells of human, mouse and opossum. These programmes are defined by the fine-tuned activities of a myriad of genes that determine the types into which cells differentiate in the course of development. Genes with cell-type-specific activity profiles were identified that have been conserved across species for at least about 160 million years of evolution. According to Henrik Kaessmann, this suggests that they are important for fundamental mechanisms that determine cell type identities in the mammalian cerebellum. At the same time, the scientists identified over 1,000 genes with activity profiles differing between human, mouse and opossum. “At the level of cell types, it happens fairly frequently that genes obtain new activity profiles. This means that ancestral genes, present in all mammals, become active in new cell types during evolution, potentially changing the properties of these cells,” says Dr Kevin Leiss, who – at the time of the studies – was a doctoral student in Prof. Kaessmann’s research group.

Among the genes showing activity profiles that differ between human and mouse – the most frequently used model organism in biomedical research – several are associated with neurodevelopmental disorders or childhood brain tumours, Prof. Pfister explains. He is a director at the Hopp Children’s Cancer Center Heidelberg, heads a research division at the German Cancer Research Center and is a consultant paediatric oncologist at Heidelberg University Hospital. The results of the study could, as Prof. Pfister suggests, provide valuable guidance in the search for suitable model systems – beyond the mouse model – to further explore such diseases.

The research results were published in the journal “Nature”. Also participating in the studies – apart from the Heidelberg scientists – were researchers from Berlin as well as China, France, Hungary, and the United Kingdom. The European Research Council financed the research. The data are available in a public database.

END

Tracing the evolution of the “little brain”

Heidelberg scientists unveil genetic programs controlling the development of cellular diversity in the cerebellum of humans and other mammals

2023-11-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bees are still being harmed despite tightened pesticide regulations

2023-11-29

A new study has confirmed that pesticides, commonly used in farmland, significantly harm bumblebees – one of the most important wild pollinators. In a huge study spanning 106 sites across eight European countries, researchers have shown that despite tightened pesticide regulations, far more needs to be done.

While the agricultural uses of insecticides have been in the spotlight for their negative effects on bees, it has remained unknown how the effects scale beyond single substances in focal ...

The Global Biodiversity Data Portal: enabling biodiversity research worldwide

2023-11-29

EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) has launched the Global Biodiversity Portal – an open access data portal that will consolidate genomic information from different biodiversity projects within the Earth BioGenome Project.

Sequencing and storing the genomic data of all species on Earth is vital for future conservation and biodiversity efforts. In an era where biodiversity is under threat from various environmental pressures, there is an urgent need for centralised, accessible, and actionable data. ...

Doctors call for expanded reporting of medical care given in ICE detention centers

2023-11-29

Embargoed until November 29 11 a.m. ET

A new study led by Dr. Annette Dekker, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at UCLA, calls for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers to increase health outcome reporting for detained immigrants to monitor the quality of medical care. Pulling from three different data sources, the researchers found discrepancies in care reported by emergency medical services (EMS) compared to ICE reports.

Building upon work that reviews deaths that occur at ICE detention centers, Dekker and colleagues sought to address concerns that individuals detained by ICE ...

Revisiting gene dosage

2023-11-29

Have you ever wondered why we carry two copies of each chromosome in all of our cells? During reproduction, we receive one from each of our parents. This means that we also receive two copies, or alleles, of each gene – one allele per chromosome or parent.

Both alleles are able to produce messenger RNA, which is the recipe needed to make proteins and keep cells running. Scientists hypothesize that having two alleles for each gene is the cell’s in-built redundancy system. If there is ever a mutation or drop in messenger RNA production from the allele carried on one of the chromosomes, the allele on the second chromosome will serve as a backup and ...

Scientists discover rare 6-planet system that moves in strange synchrony

2023-11-29

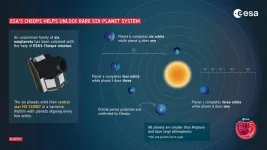

Scientists have discovered a rare sight in a nearby star system: Six planets orbiting their central star in a rhythmic beat. The planets move in an orbital waltz that repeats itself so precisely it can be readily set to music.

A rare case of an “in sync” gravitational lockstep, the system could offer deep insight into planet formation and evolution.

The analysis, led by UChicago scientist Rafael Luque, will be published Nov. 29 in Nature.

“This discovery is going to become a benchmark system to study how sub-Neptunes, the most common type of planets outside of the solar system, form, evolve, what are they made of, and if they possess the ...

Disruptive ideas rely on old fashioned meetings

2023-11-29

A marvel of modernity is the ability to collaborate with others regardless of location. Researchers can work with a colleague, maybe the only person who has a specialized skill, even if they are halfway across the globe. They can pull together a powerhouse team with a dozen of the brightest minds in the field.

Yet, according to research from the lab of Lingfei Wu, assistant professor in Pitt’s School of Computing and Information, these collaborative teams are producing fewer truly disruptive ideas or radical innovations than ...

An astronomical waltz reveals a sextuplet of planets

2023-11-29

An international collaboration between astronomers using the CHEOPS and TESS space satellites, including NCCR PlanetS members from the University of Bern and the University of Geneva, have found a key new system of six transiting planets orbiting a bright star in a harmonic rhythm. This rare property enabled the team to determine the planetary orbits which initially appeared as an unsolvable riddle.

CHEOPS is a joint mission by ESA and Switzerland, under the leadership of the University of Bern in collaboration with the University of Geneva. Thanks to a collaboration with scientists ...

Final call for Awards Nominations 2024 of the World Cultural Council

2023-11-29

The World Cultural Council (WCC) is now accepting nominations for the “Albert Einstein” World Award of Science and the “Leonardo da Vinci” World Awards of Arts.

Nominations must be submitted by 26 January, 2024. NOMINATE NOW: To nominate online or for further details of the awards visit the WCC website Nominations page.

Ideal candidates for the “Albert Einstein” World Award of Science are scientists whose achievements can serve as an inspiration for future generations. This award is granted each year. Consideration will be given to ...

BU/VA researcher awarded funding to prevent intimate partner violence

2023-11-29

(Boston)—Casey Taft, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, has been approved for a five-year, $2.8 million funding award from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) for his research study “A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate a Trauma-Informed Partner Violence Intervention Program.”

Taft, who also is a staff psychologist at the National Center for PTSD in the VA Boston Healthcare System, is conducting a randomized controlled trial of the Strength at Home program to prevent and end intimate partner violence (IPV) in Rhode Island. Strength at Home ...

The act of saying "no" under the linguistic magnifying glass

2023-11-29

FRANKFURT. Prof. Bernhard Brüne, Vice President Research, Early Career Researchers and Transfer at Goethe University Frankfurt, congratulated the researchers involved in the successful application: "Anyone who establishes a major project like a Collaborative Research Center must have both creative and viable research ideas as well as a strong network. To discover new things about language and thinking, the new CRC 1629 not only makes use of Goethe University’s structures, and the combination of philology with philosophy and didactics. It also cooperates with partner universities in Göttingen and Tübingen. Aside that, I am of course delighted that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Tracing the evolution of the “little brain”Heidelberg scientists unveil genetic programs controlling the development of cellular diversity in the cerebellum of humans and other mammals