(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – A consideration of how mountains influence El Niño and La Niña-induced precipitation change in western North America may be the ticket to more informed water conservation planning along the Colorado River, new research suggests.

The study, coinciding with a recent shift from a strong La Niña to a strong El Niño, brings a degree of precision to efforts to make more accurate winter precipitation predictions in the intermountain West by comparing 150 years of rain and snow data with historic El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns.

Overall, the analysis shows increasing winter precipitation trends in the north and decreasing trends in the south, particularly during the latter part of the 20th century. It also sheds light on how mountains both amplify and obstruct precipitation, leading to heavier rainfall to their west and lower levels of precipitation to their east.

The more accurate estimate of where and how much winter precipitation has been driven by El Niños of the past may help guide future management of resources in western North America, one of the most water-stressed parts of the world, researchers say.

“Because of the seasonality of precipitation in the West, most of it falls during the winter. If you can predict how much precipitation you’ll have in the winter, you’ll have a good sense of what your summer dry period will look like in terms of your water allocation,” said James Stagge, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of civil, environmental and geodetic engineering at The Ohio State University.

“Anything we can do to improve our ability to predict how much water we’ll get during this critical period allows cities, farmers, water managers and member states of the Colorado River Compact to prepare for upcoming drought and potentially start to go into conservation ahead of time so they’re not caught flat-footed.”

The study is published today (Dec. 4, 2023) in Nature Water.

El Niño and La Niña together constitute the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), representing warmer or cooler than normal ocean temperatures, respectively, in a section of the Pacific Ocean between South America and Australia. This anomaly has widespread impact on temperatures and precipitation – including extreme drops or increases of each – around the world.

In this study, Stagge and colleagues singled out the intermountain West, historically understudied in relation to ENSO patterns, for analysis of El Niño and La Niña wintertime precipitation effects using water gauge readings dating to 1871 – in this way, linking actual precipitation levels to not only a specific geographic location, but its elevation as well.

The readings were matched with ENSO trends documented by the Multivariate ENSO Index maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which provides real-time and historic ENSO data.

“Rather than using climate models, we’re using only observations, which allow us to be a little bit closer to reality,” Stagge said. “We didn’t use averages – we showed more precise information about where precipitation fell between the designations of El Niño and La Niña. We put each gauge in its specific location, assigned it an elevation, and looked at how it changed depending on whether it was an El Niño or La Niña year: Was it wetter or drier than normal?”

This approach unearthed finer details of historic patterns – especially in the northern portion of the intermountain region, where variations in elevation have made it more complicated to track ENSO effects on winter precipitation.

The study suggests that along this corridor, the presence of mountains can be expected to amplify the El Niño-related increase in precipitation by between 2 and 6 times – but that increase is most evident on the western side of mountains because of what is known as the orographic effect. Moist air from the Pacific moves west to east and then is pushed up over mountains into the cooler atmosphere and releases precipitation – leaving the air dry once it gets to the other side.

“All the rain falls on the west side and then by the time it gets to the east side of the mountains, there’s no more moisture to fall,” Stagge said. “Add in the effect of ENSO and it’s just like a multiplier, so the wet side gets a lot wetter during El Niño in the south, and much drier during La Niña.”

The effect of ENSO on precipitation in the region is considered a dipole, with opposite effects in the north and south, and this study supported that conclusion: Winter precipitation has tended to increase in northern Utah and Wyoming during La Niña, and winters were wetter than normal in New Mexico and Arizona during El Niño.

That said, the analysis found that the two regions don’t respond in the same way to the ENSO effect. In the south, one increment of El Niño temperature difference is linked to a corresponding increment of precipitation change. In the north, precipitation change doesn’t occur on a continuous scale based on the strength of the ENSO, but instead operates more like a light switch – it either happens or it doesn’t.

“That may have to do with the complexity of the topography,” Stagge said. “In the south, the Sierra Nevadas are not blocking the air flow, like they are for Utah and Wyoming.”

That finding has implications for water managers hoping to know what to expect in the winter, he said: Forecasts focusing on the strength of El Niño or La Niña are more informative in the north, while quantitative temperature change estimates would be more useful in the south.

Stagge hopes to connect with NOAA about combining data and modeling tools to work on forecasts for the very near future.

“Water is a determining factor in western North America. It drives the economy, it drives extremely large cities, and all of these stakeholders are concerned about it,” he said. “If we’re able to better understand or in some cases predict precipitation in this part of the world, then we have a better chance of preparing for water shortages.”

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Co-authors were Kyungmin Sung and Benjamin Phillips of Ohio State, Max Torbenson of Johannes Gutenberg University and Daniel Kingston of the University of Otago.

#

Contact: James Stagge, Stagge.11@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu; 614-292-8152

END

Collaborative ECHO research led by Megan Bragg, PhD, RD and Kristen Lyall, ScD of the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute highlights the opportunity for researchers to access the large amount of diet information already collected from the ECHO Cohort. This research, titled “Opportunities for examining child health impacts of early-life nutrition in the ECHO Program: Maternal and child dietary intake data from pregnancy to adolescence”, is published in Current Developments in Nutrition.

This study aimed to describe dietary intake data available in the ...

As one of the most insidious diseases in the world, cancer has few treatments that work to eradicate it completely. Now, a new ground-breaking approach pioneered by two researchers working at the University of Missouri’s Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building shows promising results in preventing lung cancer caused by a carcinogen in cigarettes — a discovery that immunologists Haval Shirwan and Esma Yolcu rank among the most significant of their careers.

In the new study, Shirwan and Yolcu designed a molecule — known as an immune checkpoint stimulator (SA-4-1BBL) ...

ITHACA, N.Y. – Inspired by a small and slow snail, scientists have developed a robot protype that may one day scoop up microplastics from the surfaces of oceans, seas and lakes.

The robot’s design is based on the Hawaiian apple snail (Pomacea canaliculate), a common aquarium snail that uses the undulating motion of its foot to drive water surface flow and suck in floating food particles.

Currently, plastic collection devices mostly rely on drag nets or conveyor belts to gather and remove larger plastic debris from water, but they lack the fine scale required for retrieving microplastics. These tiny particles of plastic can be ingested ...

ATLANTA — Georgia State Professor of Physics & Astronomy Stuart Jefferies has been awarded a $5 million, multi-institutional grant by the U.S. Air Force to develop techniques to detect, map and image faint objects in space.

The work could have far-reaching impacts, including strengthening national security in an increasingly congested space domain. The work will also advance the next generation of exceptionally large telescopes and improve the capabilities of astronomers studying the universe by providing images that are significantly sharper than those from existing telescopes.

“Detecting objects in the space region between where ...

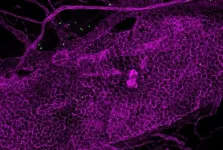

Researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine have found that controlling high blood pressure may not be enough to prevent associated cognitive declines. The findings point to an immune protein called cytokine IL-17 as a culprit for inducing dementia and suggest new approaches to prevent damage to brain cells.

The study, published on Dec. 4 in Nature Neuroscience, uncovered a new mechanism involving increased levels of IL-17 in the brain which suppressed blood flow to the brain and induced cognitive impairment in a preclinical model of salt-sensitive high blood pressure.

“An ...

At last year’s COP15 conference in Montreal, the Government of Canada set the goal of conserving 30 percent of the country’s land and water by 2030. In a new study in Nature Communications, a group of McGill University researchers have sought to understand how well our existing protected lands preserve Canadian species, how many species we could save if we reach our 30 by 30 targets, and what factors impact our ability to safeguard species in future conserved areas.

Lead author Isaac Eckert, a McGill PhD candidate in Biology, answered some questions about his research.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What ...

Toronto, ON, December 4, 2023 – There was a disproportionate rise in pediatric eating disorder hospitalizations among males, younger adolescents, and individuals with eating disorder diagnoses other than anorexia or bulimia, according to a new study from researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and ICES.

This large, population-based study spanned a 17-year period in Ontario, Canada (2002-2019), and tracked an overall increase of 139% in eating disorder hospitalizations among children and adolescents, with a total of 11,654 hospitalizations. The number of co-occurring mental illness diagnoses for ...

Contrary to current understanding, the brains of human newborns aren’t significantly less developed compared to other primate species, but appear so because so much brain development happens after birth, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, found that humans are born with brains at a development level that’s typical for similar primate species, but the human brains grow so much larger and more complex than other species after birth, it gives the false impression that human newborns are underdeveloped, or “altricial.”

Lead author Dr Aida ...

About The Study: In this prespecified secondary analysis of outcomes of 32,000 participants in a randomized clinical trial and post-trial up to 23 years later among adults with hypertension and coronary heart disease risk factors, cardiovascular disease mortality was similar between all three antihypertensive treatment groups (thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker, or angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor). ACE inhibitors increased the risk of stroke outcomes by 11% compared with diuretics, and this effect persisted well beyond the trial period.

Authors: Jose-Miguel ...

About The Study: The results of this study that included nearly 16,000 kindergarten children indicated that both total screen time and different types of content were associated with mental health problems in children ages 3 to 6. Limiting children’s screen time, prioritizing educational programs, and avoiding non–child-directed programs are recommended.

Authors: Fan Jiang, M.D., Ph.D., and Yunting Zhang, Ph.D., of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in Shanghai, China, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...