(Press-News.org) A Stanford Medicine-led, international study of hundreds of samples from patients with Hodgkin lymphoma has shown that levels of tumor DNA circulating in their blood can identify who is responding well to treatment and others who are likely to experience a disease recurrence — potentially letting some patients who are predicted to have favorable outcomes forgo lengthy treatment.

Surprisingly, the study also revealed that Hodgkin lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph nodes, can be divided into two groups, each with distinct genetic changes and slightly different prognoses. These changes hint at weaknesses in the cancer’s growth mechanisms that could be targeted by new, less toxic therapies.

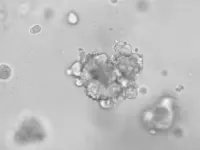

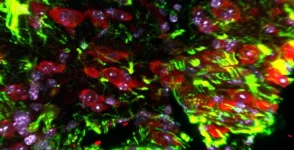

The idea of establishing molecular profiles of tumors is not new. But unlike other cancers, Hodgkin lymphoma has resisted these types of analyses. That’s because Hodgkin lymphoma cells are relatively scarce — even within a large tumor.

“This approach offers our first significant look at the genetics of classical Hodgkin lymphoma,” said professor of medicine Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD. “Compared with other cancers, finding Hodgkin lymphoma cancer cells or cancer DNA to study is like searching for a needle in a haystack. A patient can have a football-sized tumor in their chest, but only about 1% of the cells in the mass are cancer cells, with the remainder representing an inflammatory response to the tumor. This has made it very difficult to find the smoking guns that drive the disease.”

Alizadeh, who is the Moghadam Family Professor, and Maximilian Diehn, MD, PhD, professor of radiation oncology and the Jack, Lulu, and Sam Willson Professor, are the senior authors of the research, which will be published Dec. 11 in Nature. Former postdoctoral scholar Stefan Alig, MD; instructor of medicine Mohammad Shahrokh Esfahani, PhD; and graduate student Andrea Garofalo are the lead authors, as is graduate student Michael Yu Li at British Columbia Cancer.

About 8,500 people are diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma each year in the United States. The disease primarily affects people between the ages of 15 and 35, and people older than 55.

Stanford Medicine’s role

Just over 60 years ago, Stanford radiologist Henry Kaplan, MD pioneered the use of targeted radiation to treat Hodgkin lymphoma. The new therapy, delivered by a high-energy linear accelerator Kaplan developed in the 1950s for medical use, was the first step in a Stanford-driven effort to turn the once fatal cancer of the lymph nodes into one that is now highly curable. Soon thereafter, Kaplan was joined by medical oncologist Saul Rosenberg, MD, and the two worked out ways to combine radiation therapy with chemotherapy regimens, including one known simply as the Stanford 5 (named because it was the fifth in a series of gradually less toxic treatments).

During the subsequent decades, however, the genetic changes that cause the cancer have remained mysterious. That’s because, unlike many other cancers, Hodgkin lymphoma tumors are made up primarily of immune cells that have infiltrated the cancer, making it difficult to isolate the diseased cells for study. Today, patients are treated with chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of both; about 89% of patients survive five years or more after their initial diagnosis.

Alizadeh, Diehn and their colleagues used an optimized DNA sequencing technique called PhasED-Seq, or phased variant enrichment and detection sequencing, they developed at Stanford Medicine in 2021 to home in on vanishingly rare bits of DNA in a patient’s bloodstream to identify genetic changes that drive the growth of Hodgkin lymphoma.

PhasED-Seq builds upon a technique called CAPP-Seq, or cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing, developed in 2014 by Alizadeh and Diehn to assess lung cancer levels and response to treatment. But PhasED-Seq is much more sensitive.

“CAPP-Seq could detect as few as one cancer DNA sequence in 10,000 non-cancer DNA sequences,” Diehn said. “But PhasED-Seq can detect less than one cancer DNA sequence in 1 million non-cancer DNA sequences.”

Their goal was to learn more about what drives the cancer and how to make successful treatments even easier for patients.

“We typically can cure most patients with one line of therapy,” Alizadeh said. “But we are always trying to figure out less toxic chemotherapeutic agents that are gentler to the bone marrow, lungs and other organs, and ways to more precisely target radiation therapy. And a small minority of patients experience a recurrence that can be challenging to treat successfully.”

The researchers used CAPP-Seq and PhasED-Seq to analyze blood samples from 366 people treated for Hodgkin lymphoma at three medical centers including Stanford Medicine. The technique was remarkably sensitive.

“Surprisingly, we detected more cancer DNA in the blood than in the cancer tissue itself,” Alizadeh said. “That seemed hard to believe until we had analyzed enough samples to show that it was reproducible.”

Two paths

The researchers used machine learning techniques to categorize the different types of genetic changes present in the cancer cells. They found that patients could be separated into two groups: one that predominantly has mutations in several cancer-associated genes implicated in cellular survival, growth and inflammation, and another with a type of genetic change called copy number alterations that affects larger swathes of the genome, subbing in or excising regions of DNA that influence cell growth and cancer.

“We adapted a method from natural language processing to find these two Hodgkin subtypes, and then used a variety of methods to identify key biological and clinical features and to confirm that the subtypes are also seen in other groups of patients,” Esfahani said.

The first group, which makes up about one-half to two-thirds of patients, occurs primarily in younger patients and has a comparatively more favorable outcome. About 85-90% of these people survive for three years without disease recurrence. The second, which makes up about one-half to one-third of the total, occurs in both younger and older patients and has a lessfavorable, although still good outcome. About 75% of these people live for at least three years without recurrence.

Critically, a subset of both groups contained a unique mutation in a gene for the receptor for cellular signaling proteins called interleukin 4 and interleukin 13.

“We discovered a new class of mutations in the interleukin 4 receptor gene that enhance a key pathway characteristic to Hodgkin lymphoma,” Alig said. “These mutations may be indicative of unique vulnerabilities of the tumor that can be exploited therapeutically.”

The researchers also showed that patients who had no detectable circulating tumor DNA in their blood shortly after starting treatment were much less likely to have disease recurrence than those who had even small amounts of residual circulating cancer DNA at the same time point — a distinction researchers had hoped to see, but were unsure about being able to detect even with PhasED-Seq.

“I was surprised that we could predict which patients would recur,” Diehn said. “Even with our ultrasensitive assay there was a significant chance that the signal from the cancer DNA could become undetectable after treatment, even in patients who eventually recurred. But this didn’t happen.”

The researchers seeking to understand more about the biology of Hodgkin lymphoma have one key goal: the improvement of care for patients.

“The number of people who experience recurrence is small, but, like Henry Kaplan and Saul Rosenberg, we want to save every one of them,” Diehn said. “They would have been amazed and gratified by these findings, which build upon their important work from decades ago. We look forward to an era in which we can cure every patient with no toxicity.”

Researchers from British Columbia Cancer, University Hospital François Mitterand, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, KU Leuven, the University of Strasbourg, Emory University, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the Hospices Civils de Lyon, and the Université Catholique de Louvain contributed to the work.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01CA257655, R01CA233975 and R03CA21765), the Department of Defense, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, a Hanna and Michael Murphy family gift, the Stanford Cancer Institute, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, an American Society of Hematology Scholar Award, the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Emerson Collective Cancer Research Fund, a Stinehart/Reed Award, the CRK Faculty Scholar Fund, the Lung Cancer Research Foundation and the SDW/DT, the Shanahan Family Foundations, the Terry Fox Research Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, an Elizabeth C. Watters Research Fellowship, and the American Syrian Lebanese Associated Charities.

Diehn, Alizadeh, Alig and Esfahani have filed patents related to cancer biomarkers. Diehn has multiple issued and pending patents licensed to Foresight Diagnostics and Roche. He holds interests in CiberMed, Inc.; Foresight Diagnostics; and Gritstone Bio. Alizadeh has multiple issued and pending patents licensed to Foresight Diagnostics, CiberMed Inc. and Idiotype Vaccines. He holds interests in CiberMed, Inc.; Foresight Diagnostics; FortySeven Inc.; and CARGO Therapeutics.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END

Hodgkin lymphoma prognosis, biology tracked with circulating tumor DNA

Circulating tumor DNA predicts recurrence and splits disease into two subgroups in Stanford Medicine-led study of Hodgkin lymphoma. New drug targets or changes in treatments may reduce toxicity.

2023-12-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Nature and animal emojis don’t accurately represent natural biodiversity—Researchers say they should

2023-12-11

The current emoji library doesn’t accurately represent the “tree of life” and the breadth of biodiversity seen in nature according to an analysis presented December 11 in the journal iScience. A team of conservation biologists categorized emojis related to nature and animals and mapped them onto the phylogenetic tree of life. They found that animals are well represented by the current emoji catalog, whereas plants, fungi, and microorganisms are poorly represented. Within the animal kingdom, vertebrates were overrepresented while arthropods were underrepresented with respect to their actual biodiversity. The researchers argue that creating a more diverse and representative ...

Adolescent body mass index and early chronic kidney disease in young adulthood

2023-12-11

About The Study: High body mass index (BMI) in late adolescence was associated with early chronic kidney disease in young adulthood in this study that included 593,000 adolescents. The risk was also present in seemingly healthy individuals with high-normal BMI and before 30 years of age, and a greater risk was seen among those with severe obesity. These findings underscore the importance of mitigating adolescent obesity rates and managing risk factors for kidney disease in adolescents with high BMI.

Authors: Gilad Twig, M.D., Ph.D., of the Israel Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Tel Hashomer, Ramat Gan, Israel, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Prenatal exposure to GLP-1 receptor agonists and other second-line antidiabetics may not pose greater risk to infants than insulin

2023-12-11

Embargoed for release: Monday, December 11, 11:00 AM ET

Key points:

In a study of 3.5 million pregnancies across four countries between 2009 and 2021, researchers observed no elevated risk of major congenital malformations, including major cardiac malformations, among infants born to pregnant women with pre-gestational type 2 diabetes who took second-line non-insulin antidiabetic medications compared with those who took insulin.

The researchers observed an increase in use of second-line non-insulin antidiabetic ...

Potential new treatment for pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors

2023-12-11

The Organoid Group (Hubrecht Institute) and the Rare Cancers Genomics Team (IARC/WHO) found a way to grow samples of different types of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in the lab. While generating their new model, the researchers discovered that some pulmonary NETs need the protein EGF to be able to grow. These types of tumors may therefore be treatable using inhibitors of the EGF receptor. The results were published in Cancer Cell on 11 December 2023.

Neuroendocrine tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are relatively ...

AI chatbot shows potential as diagnostic partner, researchers find

2023-12-11

BOSTON – Physician-investigators at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) compared a chatbot’s probabilistic reasoning to that of human clinicians. The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, suggest that artificial intelligence could serve as useful clinical decision support tools for physicians.

“Humans struggle with probabilistic reasoning, the practice of making decisions based on calculating odds,” said the study’s corresponding author Adam Rodman, MD, an internal medicine physician and investigator in ...

Health impacts of abuse more extensive than previously thought, research says

2023-12-11

People who have been subject to abuse are more likely to experience physical and mental health effects than previously thought, according to a new study.

In a global review and meta-analysis of evidence published in Nature Medicine today, researchers have found that there are elevated risks between intimate partner violence or childhood sexual abuse, and some health conditions including major depressive disorder, maternal miscarriage for partners, and alcohol misuse and self-harm among children.

Globally, one in three ever-partnered women have experienced ...

Made-to-order diagnostic tests may be on the horizon

2023-12-11

McGill University researchers have made a breakthrough in diagnostic technology, inventing a ‘lab on a chip’ that can be 3D-printed in just 30 minutes. The chip has the potential to make on-the-spot testing widely accessible.

As part of a recent study, the results of which were published in the journal Advanced Materials, the McGill team developed capillaric chips that act as miniature laboratories. Unlike other computer microprocessors, these chips are single-use and require no external power source—a simple paper strip suffices. They function through capillary action – ...

Have researchers found the missing link that explains the mysterious phenomenon known as fairy circles?

2023-12-11

BEER-SHEVA, Israel, December 11, 2023 – Fairy circles, a nearly hexagonal pattern of bare-soil circular gaps in grasslands, initially observed in Namibia and later in other parts of the world, have fascinated and baffled scientists for years. Theories for their appearance range from spatial self-organization induced by scale-dependent water-vegetation feedback to pre-existing patterns of termite nests.

Prof. Ehud Meron of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has been studying the Namibian fairy circles as a case study for understanding how ecosystems respond to water stress. He believes that all theories ...

Study reveals a protein called snail may play a role in healing brain injury

2023-12-11

WASHINGTON (Dec. 11, 2023)--A new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Nexus provides a better understanding of how the brain responds to injuries. Researchers at the George Washington University discovered that a protein called Snail plays a key role in coordinating the response of brain cells after an injury.

The study shows that after an injury to the central nervous system (CNS) a group of localized cells start to produce Snail, a transcription factor or protein that has been implicated in the repair process.The GW researchers show that changing how much Snail is produced can significantly affect whether the injury starts ...

Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity

2023-12-11

About The Study: In participants with obesity or overweight, withdrawing tirzepatide led to substantial regain of lost weight, whereas continued treatment maintained and augmented initial weight reduction in this randomized clinical trial that included 670 adults.

Authors: Louis J. Aronne, M.D., of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2023.24945)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

[Press-News.org] Hodgkin lymphoma prognosis, biology tracked with circulating tumor DNACirculating tumor DNA predicts recurrence and splits disease into two subgroups in Stanford Medicine-led study of Hodgkin lymphoma. New drug targets or changes in treatments may reduce toxicity.