In many Western European and East Asian countries, up to 15-20% of individuals born around 1970 are now childless. Although multiple social, economic and individual preferences have been studied, there has been limited research examining the contribution of different diseases to being childless over a lifetime, particularly those diseases with onset prior to the peak reproductive age.

Dr Aoxing Liu, lead author of the study and Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki’s Institute for Molecular Medicine in Finland (FIMM) said, ‘Various factors are driving an increase in childlessness worldwide, with postponed parenthood being a significant contributor that potentially heightens the risk of involuntary childlessness. Our study is the first to systematically explore how multiple early-life diseases relate to lifetime childlessness and low parity in both men and women.’

Using nationwide registers, the researchers analysed information on 414 early-life disease diagnoses for 1.4 million women born between 1956-1973 and 1.1 million men born between 1956-1968. All were alive at the age of 16, did not emigrate, and had mostly finished their reproductive years by the end of 2018 (defined as age 45 for women, and age 50 for men).

The study’s main analyses focused on 71,524 full-sister and 77,622 full-brother pairs who exhibited differences in their childlessness status. Interestingly, the association between disease and childlessness was more alike between childless individuals and their siblings who had only one child, in comparison to those with more children.

Out of the 74 diseases significantly associated with childlessness in at least one sex, including the 33 shared among women and men, more than half of these were mental-behavioural disorders. In addition, several novel associations between disease and childlessness were discovered such as autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. A full list of the results can be found on this interactive dashboard.

A quarter of the 1.1 million men studied were childless compared to 16.6% of the 1.4 million women. Individuals with lower educational attainment in Finland and Sweden were more likely to be childless compared to the general population, and an individual's childless status was notably linked to their parents' level of education.

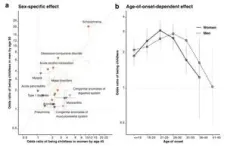

The researchers also observed significant gender differences in the relationships between diseases and childlessness. For example, schizophrenia and acute alcohol intoxication exhibited stronger associations with childlessness in men, while diabetes-related diseases and congenital anomalies showed stronger associations among women.

Sex differences were noticeable in the age of disease onset, with stronger associations earlier on for women diagnosed between the ages of 21-25, and later for men diagnosed at the age of 26-30. For instance, women diagnosed with obesity experienced higher levels of childlessness if they received their initial diagnosis between the ages of 16-20, compared to those diagnosed at a later age.

Study figure: Study figure: Sex-specific (panel a) and age-of-onset-dependent effects (panel b) for the association between disease diagnoses and childlessness in 71,524 full-sister and 77,622 full-brother pairs who were discordant on childlessness.

Professor Melinda Mills, senior author and Director of the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science at Oxford Population Health said, ‘As well as reinforcing demographic research on assortative mating and other socioeconomic factors linked to childlessness, this paper underscores the necessity for interdisciplinary research and enhanced public health emphasis on addressing early-life diseases among both men and women in relation to childlessness.’

The study also revealed that the absence of a partner played a substantial role in the connection between diseases and childlessness, accounting for an estimated 29.3% in women and 37.9% in men. Childless individuals were twice as likely to be single, whilst six diseases in women and 11 in men remained associated with childlessness among partnered individuals.

Associate Professor Andrea Ganna, senior author and FIMM-EMBL group leader at the University of Helsinki’s FIMM concluded, ‘This study reveals a connection between early-life diseases and childlessness, influencing both single and partnered women and men differently. By assessing the role of multiple early-life diseases on childlessness for 2.5 million people across Finland and Sweden, this study paves the way for a better understanding of how disease contributes to involuntary childlessness and the need for improved public health interventions.’

The study acknowledges the need for additional data to distinguish between the impacts of voluntary and involuntary childlessness, and further research to enhance the generalisability of results beyond Nordic countries and to more recent cohorts with evolving treatments, reproductive and partnering practices.

Editor’s notes

The study, 'Evidence from Finland and Sweden on the relationship between early-life diseases and lifetime childlessness in men and women', is Open Access and appears in Nature Human Behaviour: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01763-x

All results (aggregated data) can be explored on an interactive online dashboard.

For more information and interviews, please contact the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science media team (LCDS.Media@demography.ox.ac.uk) and Professor Melinda Mills (Melinda.Mills@demography.ox.ac.uk).

About the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland

The Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) is a translational research institute focusing on human genomics and personalised medicine. FIMM has a driving mission to improve the health of individuals by conducting high-impact research uncovering disease mechanisms and thereby promote precision medicine and clinical translation of research. Hosted by the Helsinki Institute of Life Science (HiLIFE) of the University of Helsinki and in close cooperative affiliation with EMBL, we aim to deliver improvements to the safety, efficacy, and efficiency of healthcare in Finland and beyond.

About the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science

Based at Oxford Population Health, the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science and Demographic Science Unit are at the forefront of demographic research, disrupting and realigning demography for the benefit of populations around the world. Focussing on inequality, family, biosocial, digital, geospatial, and computational research, our researchers use new types of data, methods and unconventional approaches to tackle the most challenging demographic and population problems of our time.

END