(Press-News.org) A new study conducted by Josh LaBaer's research team in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University has pinpointed more than 30 breast cancer gene targets ---including several novel genes---that are involved in drug resistance to a leading chemotherapy treatment.

The results of the study may one day aid in the treatment of the one in ten U.S. women who will develop breast cancer, by empowering physicians with a more personalized approach to therapy as well as a new tool for the early screening of those that may ultimately become resistant to chemotherapy.

Drugs like tamoxifen have been part of the standard treatment regimen for many breast cancer patients and saved countless lives. Unfortunately, a very serious therapeutic problem can occur when the drug loses its potency over time as women develop a resistance to the drug treatment, and tumors reemerge. Tamoxifen is an effective treatment for the 60 percent of women who are clinically diagnosed as ER+ (estrogen receptor positive), blocking hormones needed for tumor growth.

"The management of breast cancer is complicated, depending on the stage, size of tumor, and other things, but almost all ER+ women end up on tamoxifen, and it is still considered the first line of adjuvant chemotherapy ---along with resection and local radiation---used in both the early treatment of breast cancer and in late stages of the disease," said LaBaer, who holds the Virginia G. Piper Chair in Personalized Medicine at ASU and is director of the Center for Personalized Diagnostics at the Biodesign Institute. "We wanted to use a model where we could use our high-throughput technology to identify genes that encourage drug resistance to ultimately identify a signature that predicts which women will do well on a particular drug."

Using a well-established cell model for breast cancer along with the LaBaer lab's extensive collection of fully sequenced human genes, the team performed the largest genetic screen of its kind---testing the ability of 500 regulatory proteins, called kinases, that have been implicated in tumor growth and drug resistance.

"Kinases turn out to be a key drug target and we wanted to take advantage of the large number of kinase genes available in the lab," said postdoctoral researcher Laura Gonzalez, who conducted and was lead author of the study, published in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "This was the largest high-throughput screen of its kind, and it was critical to design our study in a way that we could correlate our cell studies with patients in the clinic."

By comparing gene expression patterns in cells that were sensitive (greater than 90 percent death) or resistant in response to tamoxifen, the group identified a suite of genes that failed to respond to the drug. Encouragingly, these genes were found only in the resistant cells. Furthermore, the team correlated their cell studies back to the clinic, finding a drug resistance signature that predicted the early relapse of breast cancer for women taking tamoxifen in two different clinical cohorts.

The team identified more than 30 kinases that repeated allowed the sensitive cells to grow in the presence of drug. Several were already known, but many were novel.

One of these, an atypical kinase called HSPB8, represents an entirely new mechanism for drug resistance. HSPB8 appears to confer resistance by the surprising mechanism of blocking autophagy, a process where cells escape death by consuming proteins inside the cell. This may suggest an important role for autophagy in developing resistance to tamoxifen.

"Women who had elevated levels of HSBP8 in one of our clinical cohorts, did worse on tamoxifen than women who did not," said LaBaer. "One gene alone in that cohort predicted outcome, which is very interesting. Relatively little is known about HSBP8 and so we have a gene with new territory to study."

Next, the team will investigate the role of several of the other genes identified in the study, in the hopes of contributing toward society's understanding of the underlying mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. "We will continue to use this approach as a model of what happens in women, and looking from the perspective of what genes encourage resistance. If you can find these, you can identify drugs that inhibit them," said LaBaer.

INFORMATION:

LaBaer's research is supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the NCI branch of the National Institutes of Health and a $35 million philanthropic gift from the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust.

For more information:

www.biodesign.asu.edu

Study identifies new genetic signatures of breast cancer drug resistance

2011-01-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study estimates land available for biofuel crops

2011-01-11

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Using detailed land analysis, Illinois researchers have found that biofuel crops cultivated on available land could produce up to half of the world's current fuel consumption – without affecting food crops or pastureland.

Published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, the study led by civil and environmental engineering professor Ximing Cai identified land around the globe available to produce grass crops for biofuels, with minimal impact on agriculture or the environment.

Many studies on biofuel crop viability focus on biomass yield, ...

Miscanthus has a fighting chance against weeds

2011-01-11

University of Illinois research reports that several herbicides used on corn also have good selectivity to Miscanthus x giganteus (Giant Miscanthus), a potential bioenergy feedstock.

"No herbicides are currently labeled for use in Giant Miscanthus grown for biomass," said Eric Anderson, an instructor of bioenergy for the Center of Advanced BioEnergy Research at the University of Illinois. "Our research shows that several herbicides used on corn are also safe on this rhizomatous grass."

M. x giganteus is sterile and predominantly grown by vegetative propagation, or planting ...

Lake Erie hypoxic zone doesn't affect all fish the same, study finds

2011-01-11

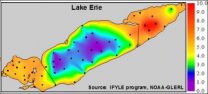

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Large hypoxic zones low in oxygen long have been thought to have negative influences on aquatic life, but a Purdue University study shows that while these so-called dead zones have an adverse affect, not all species are impacted equally.

Tomas Höök, an assistant professor of forestry and natural resources, and former Purdue postdoctoral researcher Kristen Arend used output from a model to estimate how much dissolved oxygen was present in Lake Erie's hypoxic zone each day from 1987 to 2005. That information was compared with biological ...

Being poor can suppress children's genetic potentials

2011-01-11

AUSTIN, Texas — Growing up poor can suppress a child's genetic potential to excel cognitively even before the age of 2, according to research from psychologists at The University of Texas at Austin.

Half of the gains that wealthier children show on tests of mental ability between 10 months and 2 years of age can be attributed to their genes, the study finds. But children from poorer families, who already lag behind their peers by that age, show almost no improvements that are driven by their genetic makeup.

The study of 750 sets of twins by Assistant Professor Elliot ...

Possible missing link between young and old galaxies

2011-01-11

University of California, Berkeley, astronomers may have found the missing link between gas-filled, star-forming galaxies and older, gas-depleted galaxies typically characterized as "red and dead."

In a poster to be presented this week at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle, UC Berkeley astronomers report that a long-known "early-type" galaxy, NGC 1266, is expelling molecular gas, mostly hydrogen, from its core.

Astronomers have long recognized the distinction between early-type red and dead galaxies, thought to be largely devoid of gas and dust and ...

Oxygen-free early oceans likely delayed rise of life on planet

2011-01-11

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Geologists at the University of California, Riverside have found chemical evidence in 2.6-billion-year-old rocks that indicates that Earth's ancient oceans were oxygen-free and, surprisingly, contained abundant hydrogen sulfide in some areas.

"We are the first to show that ample hydrogen sulfide in the ocean was possible this early in Earth's history," said Timothy Lyons, a professor of biogeochemistry and the senior investigator in the study, which appears in the February issue of Geology. "This surprising finding adds to growing evidence showing ...

Does it hurt?

2011-01-11

It is well known that pain is a highly subjective experience. We each have a pain threshold, but this can vary depending on distractions and mood. A paper in the International Journal of Behavioural and Healthcare Research offers a cautionary note on measuring perceived pain in research.

There are many chronic illnesses and injuries that have no well-defined symptoms other than pain, but because of the subjectivity in a patient's reporting of their experience of the illness or injury, healthcare workers have difficulty in addressing the patient's needs. Moreover, when ...

New method takes snapshots of proteins as they fold

2011-01-11

People have only 20,000 to 30,000 genes (the number is hotly contested), but they use those genes to make more than 2 million proteins. It's the protein molecules that domost of the work in the human cell. After all, the word protein comes from the Greek prota, meaning "of primary importance."

Proteins are created as chains of amino acids, and these chains of usually fold spontaneously into what is called their "native form" in milliseconds or a few seconds.

A protein's function depends sensitively on its shape. For example, enzymes and the molecules they alter are ...

Universities miss chance to identify depressed students

2011-01-11

CHICAGO --- One out of every four or five students who visits a university health center for a routine cold or sore throat turns out to be depressed, but most centers miss the opportunity to identify these students because they don't screen for depression, according to new Northwestern Medicine research.

About 2 to 3 percent of these depressed students have had suicidal thoughts or are considering suicide, the study found.

"Depression screening is easy to do, we know it works, and it can save lives," said Michael Fleming, professor of family and community medicine ...

'Hot-bunking' bacterium recycles iron to boost ocean metabolism

2011-01-11

In the vast ocean where an essential nutrient—iron—is scarce, a marine bacterium that launches the ocean food web survives by using a remarkable biochemical trick: It recycles iron.

By day, it uses iron in enzymes for photosynthesis to make carbohydrates; then by night, it appears to reuse the same iron in different enzymes to produce organic nitrogen for proteins.

The bacterium, Crocosphaera watsonii, is one of the few marine microbes that can convert nitrogen gas into organic nitrogen, which (just as it does on land) acts as fertilizer to stimulate plant growth in ...