(Press-News.org) A decades-old mystery of how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria are able to recognize and kill other bacteria may have been solved, according to new research.

In a study published today (4th January) in Nature Microbiology, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham have discovered how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria, called Bdellovibrio bacterivorous, produce fibre-like proteins on their surface to ensnare prey.

This discovery may enable scientists to use these predators to target and kill problematic bacteria that cause issues in healthcare, food spoilage and the environment.

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust Investigator in Science Award (209437/Z/17/Z).

Professor of Structural Biology at the University of Birmingham, Andrew Lovering said: “Since the 1960s Bdellovibrio bacterivorous has been known to hunt and kill other bacteria by entering the target cells and eating them from the inside before later bursting out. The question that had stumped scientists was ‘how do these cells make a firm attachment when we know how varied their bacterial targets are?’”

Professor Lovering and Professor Liz Sockett, from the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham, have been collaborating in this field for almost 15 years. The breakthrough came when Sam Greenwood an undergraduate student, and Asmaa Al-Bayati, a PhD student in the Sockett lab, discovered that the Bdellovibrio predators lay down a sturdy vesicle (a “pinched-off” part of the predator cell envelope) when invading their prey.

Professor Liz Sockett explained: “The vesicle creates a kind of airlock or keyhole allowing Bdellovibrio entry into the prey cell. We were then able to isolate this vesicle from the dead prey, which is a first in this field. The vesicle was analysed to reveal the tools used during the preceding event of predator/prey contact. We thought of it as a bit like a locksmith leaving the pick, or key, as evidence, in the keyhole.

“By looking at the vesicle contents, we discovered that because Bdellovibrio doesn’t know which bacteria it will meet, it deploys a range of similar prey recognition molecules on its surface, creating lots of different ‘keys’ to ‘unlock’ lots of different types of prey.”

The researchers then undertook an individual analysis of the molecules, demonstrating that they form long fibres, approximately ten times longer than common globular proteins. This allows them to operate at a distance and “feel” for prey in the vicinity.

In total, the labs counted 21 different fibres. Researchers Dr Simon Caulton, Dr Carey Lambert and Dr Jess Tyson worked on how they operated both at the cellular and molecular level. They were supported by fibre gene-engineering by Paul Radford and Rob Till. The team then began to attempt linking a particular fibre to a particular prey-surface molecule. Finding out which fibre matches which prey, could enable an engineering approach which sees bespoke predators targeting different types of bacteria.

Professor Lovering continued: “Because the predator strain we were looking at comes from the soil it has a wide killing range, making this identification of these fibre and prey pairs very difficult. However, on the fifth attempt to find the partners we discovered a chemical signature on the outside of prey bacteria that was a tight fit to the fibre tip. This is the first time a feature of Bdellovibrio has been matched to prey selection.”

Scientists in this field will now be able to use these discoveries to ask which fibre set is used by the different predators they study and potentially attribute these to specific prey. Improving understanding of these predator bacteria could enable their usage as antibiotics, to kill bacteria that degrade food, or ones which are harmful to the environment.

Professor Lovering concluded: “We know that these bacteria can be helpful, and by fully understanding how they operate and find their prey, it opens up a world of new discoveries and possibilities.”

ENDS

END

Breakthrough could dramatically cut the use of pesticides and unlock other opportunities to bolster plant health

Scientists have engineered the microbiome of plants for the first time, boosting the prevalence of ‘good’ bacteria that protect the plant from disease.

The findings published in Nature Communications by researchers from the University of Southampton, China and Austria, could substantially reduce the need for environmentally destructive pesticides.

There is growing public awareness about the significance of our microbiome – the myriad of microorganisms that live in and around our bodies, most notably in our guts. Our gut ...

Introduction to the Event: As the world witnesses rapid technological advancements and the increasing reality of space travel and habitation, Chiba University is taking the lead in shaping the dialogue on the future of space development and humanity. The upcoming conference will feature distinguished speakers from Chiba University and international institutions, converging to facilitate interdisciplinary discussions. Through diverse lenses encompassing philosophy, ethics, law, political science, and horticulture, the conference aims to gain profound insights, welcoming active ...

In light of an estimated replication rate of only 36% out of 100 replication attempts conducted by the Open Science Collaboration in 2015 (OSC2015), many believe that experimental psychology suffers from a severe replicability problem.

In their own study, recently published in the open-access peer-reviewed scientific journal Social Psychological Bulletin, Drs Brent M. Wilson and John T. Wixted at the University of California San Diego (USA) suggest that what has since been referred to as a “replication crisis” might not be as bad as it seems.

“No one asks a critical question,” the scientists argue, “if ...

Overview

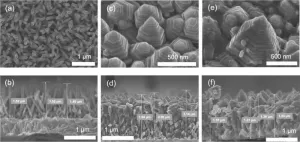

A research team consisting of members of the Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute and the Functional Materials Engineering Laboratory at the Toyohashi University of Technology, has developed a novel high-performance photoelectrode by constructing a zinc oxide nanopagoda array with a unique shape on a transparent electrode and applying silver nanoparticles to its surface. The zinc oxide nanopagoda is characterized by having many step structures, as it comprises stacks of differently sized hexagonal prisms. In addition, it exhibits very few crystal defects and excellent electron conductivity. By decorating its surface with silver nanoparticles, the zinc oxide nanopagoda ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University researchers have discovered vitamin B1 produced by microbes in rivers, findings that may offer hope for vitamin-deficient salmon populations.

Findings were published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

The authors say the study in California’s Central Valley represents a novel piece of an important physiological puzzle involving Chinook salmon, a keystone species that holds significant cultural, ecological and economic importance in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Christopher ...

Overview

A research team from the Institute for Research on Next-generation Semiconductor and Sensing Science (IRES²) at the Toyohashi University of Technology, National Institute of Technology, Ibaraki College, and TechnoPro R&D Company has successfully demonstrated low-invasive neural recording technology for the brain tissue of diabetic mice. This was achieved using a small needle-electrode with a diameter of 4 µm. Recording neuronal activity within the diabetic brain tissue is particularly challenging due to various complications, including the development of cerebrovascular disease. Because of the significant advantage of the miniaturized needle-electrode compared to conventional ...

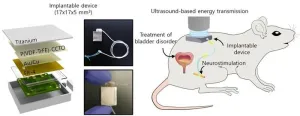

Medical technology innovations achieved by integrating science and medicine have improved the quality of life for patients. Especially noteworthy is the emergence of electronic devices implanted in the body, such as in the heart or brain, which enable real-time measurement and regulation of physiological signals, presenting new solutions for challenging conditions like Parkinson's disease. However, technical constraints have hindered the semi-permanent use of electronic devices after their implantation.

A collaborative research team led by Professor Sung-Min Park from the Departments of Convergence IT Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, and ...

LOS ANGELES — Hearing loss affects approximately 40 million American adults, yet only one in 10 people who need hearing aids use them, research shows.

Those who don’t use hearing aids but should may want to make wearing them one of their New Year’s resolutions, according to a new study from Keck Medicine of USC published today in The Lancet Healthy Longevity.

“We found that adults with hearing loss who regularly used hearing aids had a 24% lower risk of mortality than those who never wore them,” ...

Australian researchers have successfully trialled a novel experiment to address offensive and rude comments in operating theatres by placing ‘eye’ signage in surgical rooms.

The eye images, attached to the walls of an Adelaide orthopaedic hospital’s operating theatre without any explanation, had the desired effect in markedly reducing poor behaviour among surgical teams.

Lead researcher University of South Australia Professor Cheri Ostroff attributed the result to a perception of being “watched”, even though the eyes were not real.

The three-month experiment ...

The avocado has soared to unprecedented heights of popularity, gracing the plates of toast enthusiasts and health-conscious individuals worldwide. But what are the overlooked consequences of our latest food obsession?

“The avocado has come to represent so much more than just a fruit. It’s wrapped up with ideas of generational conflict, environmental chaos and social injustice. Over the last century, through careful marketing, it has evolved into a commodity crop with a huge social media following.” says Honor May Eldridge, a food policy expert who works to promote sustainable agriculture around the ...