(Press-News.org) The gut microbiome is so useful to human digestion and health that it is often called an extra digestive organ. This vast collection of bacteria and other microorganisms in the intestine helps us break down foods and produce nutrients or other metabolites that impact human health in a myriad of ways. New research from the University of Chicago shows that some groups of these microbial helpers are amazingly resourceful too, with a large repertoire of genes that help them generate energy for themselves and potentially influence human health as well.

The paper, published January 4, 2024, in Nature Microbiology, identified 22 metabolites that three distantly related families of gut bacteria use as alternatives to oxygen for respiration in the anaerobic environment of the gut. These bacteria also have up to hundreds of copies of genes for producing the enzymes that process these alternate metabolites – many more than have been measured in bacteria that live outside the gut. These results suggest that anaerobic gut bacteria may have the ability to produce energy from hundreds of other compounds as well.

“These are examples of some of the peculiar metabolisms that act on all these different metabolites produced by the gut microbiome,” said Sam Light, PhD, Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Microbiology at UChicago and senior author of the study. “This is interesting because one of the main ways the microbiome impacts our health is by making or modifying these small molecules that can then enter our bloodstream and act like drugs.”

At the organism level, we typically think of respiration as the process of breathing in oxygen. At the cellular level, respiration describes an energy-generating biochemical process. Most cells use oxygen for respiration, but in anaerobic environments like the inside of the intestine, cells have evolved to use other molecules.

Cells possess two main types of metabolism to produce energy: fermentation and respiration. In fermentation, the cell breaks down molecules to generate energy directly. Respiration involves two molecules: an electron donor and an electron acceptor. A classic example of this process uses glucose as a donor and oxygen as the acceptor. The cells break down the glucose by shuttling extracted electrons through a series of steps before their final transfer to an oxygen molecule. This prompts the cell to generate ATP, or adenosine triphosphate: the basic source of energy for use and storage at the cellular level.

Most of the microbes living in the gut use fermentation, but there are also several known types of bacteria with respiratory metabolisms, including those that use carbon dioxide and sulfate electron acceptors. For the new study, Light and his colleagues analyzed a database of more than 1,500 genomes from a database of human gut bacteria. They saw a surprising distribution of genes that produce reductases, which are enzymes that use different respiratory electron acceptors. While most of the genomes encode just a few reductases, a small subset encodes more than 30 different ones. These bacteria weren’t closely related; they came from three distinct and distantly related families (Burkholderiaceae, Eggerthellaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae) separated by hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary history.

These bacteria appear to be more resourceful than bacteria with respiratory metabolisms that live outside of a host organism, which mostly use inorganic compounds. The respiratory gut bacteria Light and team identified specialize in various organic metabolites, which makes sense given the constant food supply.

"There is so much organic matter in the gut that comes from the food we eat. It’s chemically complex, and you need more enzymes to accommodate it in that environment,” Light said. “We think this variety of genes enables gut bacteria to use a lot of different things that come their way.”

Some of the metabolites they use also have interesting implications for human health in the gut. People with type 2 diabetes, for example, have higher levels of an amino acid byproduct called imidazole propionate in their blood. Another metabolite, resveratrol, impacts several metabolic and immune system processes, and itaconate is produced by macrophages in response to infections.

Light hopes that more research like this will help us understand the function of different microbes in the gut, which can in turn be leveraged to improve health.

“I'm hoping our understanding of these different metabolisms and how they work will enable us to come up with strategies to intervene – either through the diet or pharmacologically – to modulate the flow of metabolites through these various pathways,” he said. "So, in whatever context, like type 2 diabetes or following an infection, we could control which metabolites are being produced to have a therapeutic benefit.”

The study, “Dietary- and host-derived metabolites are used by diverse gut bacteria for anaerobic respiration,” was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (T32DK007074, 1S10OD020062-01, K22AI144031, and R35GM146969) and the Searle Scholars Program. Additional authors include Alexander S. Little, Isaac T. Younker, Matthew S. Schechter, Paola Nol Bernardino, Joshua Stemczynski, Kaylie Scorza, Michael W. Mullowney, Deepti Sharan, Emily Waligurski, Rita Smith, Ramanujam Ramanswamy, William Leiter, David Moran, Mary McMillin, Matthew A. Odenwald, Ashley M. Sidebottom, Anitha Sundararajan and Eric G. Pamer from the University of Chicago; Raphaël Méheust from Université d'Évry and Université Paris-Saclay, France; Anthony T. Iavarone from the University of California, Berkeley; and A. Murat Eren from the University of Oldenburg, Germany.

END

The surprisingly resourceful ways bacteria thrive in the human gut

Survey of bacterial genomes highlights the arsenal of enzymes microbes use to produce energy in the oxygen-poor environment of the gut

2024-01-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genomic ‘tweezer’ ushers in a new era of precision in microbiome research

2024-01-04

In a landmark study recently published in the journal Nature Methods, researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have unveiled mEnrich-seq—an innovative method designed to substantially enhance the specificity and efficiency of research into microbiomes, the complex communities of microorganisms that inhabit the human body.

Unlocking the Microbial World with mEnrich-seq

Microbiomes play a crucial role in human health. An imbalance or a decrease in the variety of microbes in our bodies can lead to an increased risk of several diseases. However, in many microbiome applications, the focus is on studying specific ...

Scientists tame chaotic protein fueling 75% of cancers

2024-01-04

Meet MYC, the shapeless protein responsible for making the majority of human cancer cases worse. UC Riverside researchers have found a way to rein it in, offering hope for a new era of treatments.

In healthy cells, MYC helps guide the process of transcription, in which genetic information is converted from DNA into RNA and, eventually, into proteins. “Normally, MYC’s activity is strictly controlled. In cancer cells, it becomes hyper active, and is not regulated properly,” said UCR associate professor of chemistry Min Xue.

“MYC is less like food for cancer cells and more like a steroid ...

Breakthrough in designing complicated all-α protein structures

2024-01-04

A team of researchers has developed an innovative method to design complicated all-α proteins, characterized by their non-uniformly arranged α-helices as seen in hemoglobin. Employing their novel approach, the team successfully created five unique all-α protein structures, each distinguished by their complicated arrangements of α-helices. This capability holds immense potential in designing functional proteins.

This research has been published in the journal Nature Structural and Molecular Biology on January 4, 2024.

Proteins fold into unique three-dimensional structures based on their amino acid sequences, which then dictate their ...

Scientists solve mystery of how predatory bacteria recognizes prey

2024-01-04

A decades-old mystery of how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria are able to recognize and kill other bacteria may have been solved, according to new research.

In a study published today (4th January) in Nature Microbiology, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham have discovered how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria, called Bdellovibrio bacterivorous, produce fibre-like proteins on their surface to ensnare prey.

This discovery may enable scientists to use these predators to target and kill ...

Scientists engineer plant microbiome for the first time to protect crops against disease

2024-01-04

Breakthrough could dramatically cut the use of pesticides and unlock other opportunities to bolster plant health

Scientists have engineered the microbiome of plants for the first time, boosting the prevalence of ‘good’ bacteria that protect the plant from disease.

The findings published in Nature Communications by researchers from the University of Southampton, China and Austria, could substantially reduce the need for environmentally destructive pesticides.

There is growing public awareness about the significance of our microbiome – the myriad of microorganisms that live in and around our bodies, most notably in our guts. Our gut ...

Chiba University is pleased to announce the International Conference: “Humanities In The Age Of Space Exploration”

2024-01-04

Introduction to the Event: As the world witnesses rapid technological advancements and the increasing reality of space travel and habitation, Chiba University is taking the lead in shaping the dialogue on the future of space development and humanity. The upcoming conference will feature distinguished speakers from Chiba University and international institutions, converging to facilitate interdisciplinary discussions. Through diverse lenses encompassing philosophy, ethics, law, political science, and horticulture, the conference aims to gain profound insights, welcoming active ...

US study offers a different explanation why only 36% of psychology studies replicate

2024-01-04

In light of an estimated replication rate of only 36% out of 100 replication attempts conducted by the Open Science Collaboration in 2015 (OSC2015), many believe that experimental psychology suffers from a severe replicability problem.

In their own study, recently published in the open-access peer-reviewed scientific journal Social Psychological Bulletin, Drs Brent M. Wilson and John T. Wixted at the University of California San Diego (USA) suggest that what has since been referred to as a “replication crisis” might not be as bad as it seems.

“No one asks a critical question,” the scientists argue, “if ...

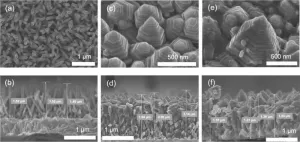

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode

2024-01-04

Overview

A research team consisting of members of the Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute and the Functional Materials Engineering Laboratory at the Toyohashi University of Technology, has developed a novel high-performance photoelectrode by constructing a zinc oxide nanopagoda array with a unique shape on a transparent electrode and applying silver nanoparticles to its surface. The zinc oxide nanopagoda is characterized by having many step structures, as it comprises stacks of differently sized hexagonal prisms. In addition, it exhibits very few crystal defects and excellent electron conductivity. By decorating its surface with silver nanoparticles, the zinc oxide nanopagoda ...

Vitamin discovered in rivers may offer hope for salmon suffering from thiamine deficiency disease

2024-01-04

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University researchers have discovered vitamin B1 produced by microbes in rivers, findings that may offer hope for vitamin-deficient salmon populations.

Findings were published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

The authors say the study in California’s Central Valley represents a novel piece of an important physiological puzzle involving Chinook salmon, a keystone species that holds significant cultural, ecological and economic importance in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Christopher ...

An electrophysiological breakthrough for diabetic brain studies

2024-01-04

Overview

A research team from the Institute for Research on Next-generation Semiconductor and Sensing Science (IRES²) at the Toyohashi University of Technology, National Institute of Technology, Ibaraki College, and TechnoPro R&D Company has successfully demonstrated low-invasive neural recording technology for the brain tissue of diabetic mice. This was achieved using a small needle-electrode with a diameter of 4 µm. Recording neuronal activity within the diabetic brain tissue is particularly challenging due to various complications, including the development of cerebrovascular disease. Because of the significant advantage of the miniaturized needle-electrode compared to conventional ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] The surprisingly resourceful ways bacteria thrive in the human gutSurvey of bacterial genomes highlights the arsenal of enzymes microbes use to produce energy in the oxygen-poor environment of the gut