Research identifies drug target for prion diseases, 'mad cow'

University of Kentucky scientists make discovery

2011-01-11

(Press-News.org) LEXINGTON, Ky. (Jan. 4, 2011) − Scientists at the University of Kentucky have discovered that plasminogen, a protein used by the body to break up blood clots, speeds up the progress of prion diseases such as mad cow disease.

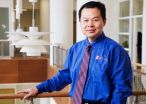

This finding makes plasminogen a promising new target for the development of drugs to treat prion diseases in humans and animals, says study senior author Chongsuk Ryou, a researcher at the UK Sanders-Brown Center on Aging and professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics in the UK College of Medicine.

"I hope that our study will aid in developing therapy for prion diseases, which will ultimately improve the quality of life of patients suffering from prion diseases," Ryou said. "Since prion diseases can lay undetected for decades, delaying the ability of the disease-associated prion protein to replicate by targeting the cofactor of the process could be a monumental implication for treatment."

The study was reported in the December issue of The FASEB Journal (www.fasebj.org), published by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

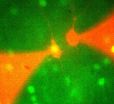

Ryou's team used simple test-tube reactions to multiply disease-associated prion proteins. The reactions were conducted in the presence or absence of plasminogen. They also found that the natural replication of the prions was stimulated by plasminogen in animal cells.

"Rogue prions are one of nature's most interesting, deadly and least understood biological freak shows," says Dr. Gerald Weissmann, editor-in-chief of The FASEB Journal. "They are neither virus nor bacteria, but they kill or harm you just the same. By showing how prions hijack our own clot-busting machinery, this work points to a new target for anti-prion therapy."

According to the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, prion diseases are a related group of rare, fatal brain diseases that affect animals and humans. The diseases are characterized by certain misshapen protein molecules that appear in brain tissue. Normal forms of these prion protein molecules reside on the surface of many types of cells, including brain cells, but scientists do not understand what normal prion protein does. On the other hand, scientists believe that abnormal prion protein, which clumps together and accumulates in brain tissue, is the likely cause of the brain damage that occurs. Scientists do not have a good understanding of what causes the normal prion protein to take on the misshapen abnormal form.

Prion diseases are also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, and include bovine spongiform encephalopathy ("mad cow" disease) in cattle; Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans; scrapie in sheep; and chronic wasting disease in deer and elk. These proteins may be spread through certain types of contact with infected tissue, body fluids, and possibly, contaminated medical instruments.

The co-author of the study is Charles E. Mays, formerly a graduate student in the Ryou lab.

INFORMATION: END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011-01-11

Alexandria, VA – Where to next in the search for oil and gas? EARTH examines several possible new frontiers - including the Arctic, the Falkland Islands, the Levant, Trinidad and Tobago and Sudan - where oil and gas exploration are starting to take hold. One of those places, Sudan, is in the news for other reasons: South Sudan voted yesterday on whether to secede from North Sudan.

But given that South Sudan holds more than 70 percent of Sudan's 5 billion to 6 billion barrels of proven reserves, a lot in this election hinges on oil. If South Sudan does secede, how will ...

2011-01-11

PITTSBURGH—Carnegie Mellon University researchers have found that within the brain's neocortex lies a subnetwork of highly active neurons that behave much like people in social networks. Like Facebook, these neuronal networks have a small population of highly active members who give and receive more information than the majority of other members, says Alison Barth, associate professor of biological sciences at Carnegie Mellon and a member of the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition (CNBC). By identifying these neurons, scientists will now be able to study them further ...

2011-01-11

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. – Firms that outsource aspects of their business to a foreign country may profit by saving money, but the practice tends to soften the competition among industry rivals, exacting a hidden cost on consumers, says new research co-written by a University of Illinois business administration professor.

Yunchuan "Frank" Liu says outsourcing hurts society in two ways – it results in lost jobs for workers, and in consumers paying higher prices than they should for goods.

"Outsourcing is a topic that affects just about everyone, and the general consensus is that ...

2011-01-11

The mechanism for binding oxygen to metalloporphyrins is a vital process for oxygen-breathing organisms. Understanding how small gas molecules are chemically bound to the metal complex is also important in catalysis or the implementation of chemical sensors. When investigating these binding mechanisms, scientists use porphyrin rings with a central cobalt or iron atom. They coat a copper or silver support surface with these substances.

An important characteristic of porphyrins is their conformational flexibility. Recent research has shown that each specific geometric configuration ...

2011-01-11

Instances of cyber bullying continue to make news nearly every day, and while it's recognized as a problem among most school-aged children, a new study published this month in Children & Schools and coauthored by Temple University social work professor Jonathan Singer finds that nearly half of school social workers feel they are ill equipped to handle it.

"School social workers provide more crisis intervention services than any other school staff member – more than counselors, nurses, teachers, or psychologists," said Singer. "As a result, school social workers are a ...

2011-01-11

VIDEO:

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have developed liquid pistons, which can be used to precisely pump small volumes of liquid. Comprising the pistons are droplets of nanoparticle-infused ferrofluids, which can...

Click here for more information.

Troy, N.Y. – A few unassuming drops of liquid locked in a very precise game of "follow the leader" could one day be found in mobile phone cameras, medical imaging equipment, implantable drug delivery devices, ...

2011-01-11

Researchers at Nationwide Children's Hospital report a gene therapy strategy that improves the condition of a mouse model of an inherited blood disorder, Beta Thalassemia. The gene correction involves using unfertilized eggs from afflicted mice to produce a batch of embryonic stem cell lines. Some of these stem cell lines do not inherit the disease gene and can thus be used for transplantation-based treatments of the same mice. Findings could hold promise for a new treatment strategy for autosomal dominant diseases like certain forms of Beta Thalassemia, tuberous sclerosis ...

2011-01-11

Using biological samples taken from patients and state-of-the-art biochemical techniques, a Florida State University researcher is working to identify a variety of "biomarkers" that might provide earlier warnings of the presence of breast and prostate cancers.

"Biomarkers are indicators of certain biological and pathological processes that are occurring, such as cancer," said Qing-Xiang "Amy" Sang, a professor in Florida State's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. "Either the cancer cells themselves, or surrounding normal tissue for that matter, can produce specific ...

2011-01-11

UCLA researchers have found that a protein that plays an important role in some antioxidant therapies may not be as effective due to additional mechanisms that cause it to promote atherosclerosis, or clogging of the arteries.

Published in the January issue of the journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, the finding may give clues as to why some antioxidant therapies have not yielded more positive results.

The protein, called Nrf2, has been thought to be an important drug-therapy target for diseases such as cancer because it can induce chemopreventive ...

2011-01-11

Persistence paid off for a University of Alberta paleontology researcher, who after months of pondering the origins of a fossilized jaw bone, finally identified it as a new species of pterosaur, a flying reptile that lived 70 million years ago.

Victoria Arbour says she was stumped when the small piece of jaw bone was first pulled out of of a fossil storage cabinet in the U of A's paleontology department.

"It could have been from a dinosaur, a fish or a marine reptile," said Arbour. "

Arbour, a PhD student in paleontology, says the first clue to the fossil's identify ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research identifies drug target for prion diseases, 'mad cow'

University of Kentucky scientists make discovery