(Press-News.org) Levi Gadye, 628-399-1046

Levi.Gadye@ucsf.edu | @UCSF

Video: https://ucsf.app.box.com/s/i3atd54ye4m1z1spi0qf59axq7tq7640

Subscribe to UCSF News

A high-sugar diet is bad news for humans, leading to diabetes, obesity and even cancer. Yet fruit bats survive and even thrive by eating up to twice their body weight in sugary fruit every day.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have discovered how fruit bats may have evolved to consume so much sugar, with potential implications for the 37 million Americans with diabetes. The findings, published on Tuesday, Jan. 9, 2024 in Nature Communications, point to adaptations in the fruit bat body that prevent their sugar-rich diet from becoming harmful.

Diabetes is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it’s responsible for $237 billion in direct medical costs each year.

“With diabetes, the human body can’t produce or detect insulin, leading to problems controlling blood sugar,” said Nadav Ahituv, PhD, director of the UCSF Institute for Human Genetics and co-senior author of the paper. “But fruit bats have a genetic system that controls blood sugar without fail. We’d like to learn from that system to make better insulin- or sugar-sensing therapies for people.”

Ahituv’s team focused on evolution in the bat pancreas, which controls blood sugar, and the kidneys. They found that the fruit bat pancreas, compared to the pancreas of an insect-eating bat, had extra insulin-producing cells as well as genetic changes to help it process an immense amount of sugar. And fruit bat kidneys had adapted to ensure that vital electrolytes would be retained from their watery meals.

“Even small changes, to single letters of DNA, make this diet viable for fruit bats,” said Wei Gordon, PhD, co-first author of the paper, a recent graduate of UCSF’s TETRAD program, and assistant professor of biology at Menlo College. “We need to understand high-sugar metabolism like this to make progress helping the one in three Americans who are prediabetic.”

A sweet tooth without consequences

Each day, after 20 hours of sleep, fruit bats wake up for four hours to gorge on fruit. Then it’s back to the roost.

To understand how a fruit bat pulls off this feat of sugar consumption, Ahituv and Gordon collaborated with scientists from a variety of institutions, ranging from Yonsei University in Korea to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, to compare the Jamaican fruit bat to the big brown bat, which only eats insects.

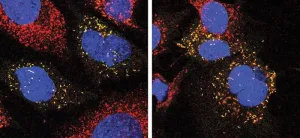

The researchers analyzed gene expression (which genes were on or off) and regulatory DNA (the parts of DNA that control gene expression) using a method for measuring both in individual cells.

“This newer single-cell technology can explain not only which types of cells are in which organs, but also how those cells regulate gene expression to manage each diet,” Ahituv said.

In fruit bats, the compositions of the pancreas and kidneys evolved to accommodate their diet. The pancreas had more cells to produce insulin, which tells the body to lower blood sugar, as well as more cells to produce glucagon, the other major sugar-regulating hormone. The fruit bat kidneys, meanwhile, had more cells to trap scarce salts as they filter blood.

Zooming in, the regulatory DNA in those cells had evolved to turn the appropriate genes for fruit metabolism on or off. The big brown bat, on the other hand, had more cells for breaking down protein and conserving water. And the gene expression in those cells was tuned to handle a diet of bugs.

“The organization of the DNA around the insulin and glucagon genes was very clearly different between the two bat species,” Gordon said. “The DNA around genes used to be considered ‘junk,’ but our data shows that this regulatory DNA likely helps fruit bats react to sudden increases or decreases in blood sugar.”

While some of the biology of the fruit bat resembled what’s found in humans with diabetes, the fruit bat appeared to evolve something that humans with a sweet tooth could only dream of: a sweet tooth without consequences.

“It’s remarkable to step back from model organisms, like the laboratory mouse, and discover possible solutions for human health crises out in nature,” Gordon said. “Bats have figured it out, and it’s all in their DNA, the result of natural selection.”

Superheroes of evolution

The study benefited from a recent groundswell of interest in studying bats to better human health. Gordon and Ahituv traveled to Belize to participate in an annual Bat-a-Thon with nearly 50 other bat researchers, taking a census of wild bats as well as field samples for science. One of the Jamaican fruit bats captured at this event was used in the sugar metabolism study.

As one of the most diverse families of mammals, bats include many examples of evolutionary triumph, from their immune systems to their peculiar diets and beyond.

“For me, bats are like superheroes, each one with an amazing super power, whether it is echolocation, flying, blood sucking without coagulation, or eating fruit and not getting diabetes,” Ahituv said. “This kind of work is just the beginning.”

Key collaborators included co-first author Seungbyn Baek, PhD, from Yonsei University (South Korea); co-senior author Martin Hemberg, PhD, from Harvard Medical School; Tony Schountz, PhD, from Colorado State University; Lisa Noelle Cooper, PhD, from Northeast Ohio Medical University; Melissa R. Ingala, PhD, Fairleigh Dickinson University; and Nancy B. Simmons, PhD, American Museum of Natural History. Other UCSF authors are Hai P. Nguyen, PhD, Yien-Ming Kuo, PhD, Rachael Bradley, and Sarah L. Fong, PhD. For all authors see the paper.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at https://ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

How fruit bats got a sweet tooth without sour health

2024-01-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Vaccine demonstrates potential in delaying relapse of KRAS-mutated pancreatic and colorectal cancers

2024-01-09

HOUSTON ― A vaccine showed potential to prevent relapse of KRAS-mutated pancreatic and colorectal cancers for patients who had previously undergone surgery, according to a Phase I trial led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Results were published today in Nature Medicine.

In the trial, patients with pancreatic and colorectal cancer who were considered at high risk of relapse received a maximum of 10 doses of the ELI-002 vaccine targeted toward KRAS G12D and G12R mutations. T cell responses were seen in 84% of all patients and in 100% of those in the two highest dose cohorts, including those who ...

Smart skin bacteria are able to secrete and produce molecules to treat acne

2024-01-09

International research led by the Translational Synthetic Biology Laboratory of the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS) at Pompeu Fabra University has succeeded in efficiently engineering Cutibacterium acnes -a type of skin bacterium- to produce and secrete a therapeutic molecule suitable for treating acne symptoms. The engineered bacterium has been validated in skin cell lines and its delivery has been validated in mice. This finding opens the door to broadening the way for engineering non-tractable bacteria to address skin alterations and other diseases using living therapeutics.

The research team is completed by scientists from the Bellvitge Biomedical Research ...

Stranger than friction: A force initiating life

2024-01-09

As the potter works the spinning wheel, the friction between their hands and the soft clay helps them shape it into all kinds of forms and creations. In a fascinating parallel, sea squirt oocytes (immature egg cells) harness friction within various compartments in their interior to undergo developmental changes after conception. A study from the Heisenberg group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), published in Nature Physics, now describes how this works.

The sea is full of fascinating life forms. From algae and colorful fish to marine snails and sea squirts, a completely different world reveals itself underwater. Sea squirts or ascidians in particular are very unusual: ...

Different biological variants discovered in Alzheimer's disease

2024-01-09

Dutch scientists have discovered five biological variants of Alzheimer's disease, which may require different treatment. As a result, previously tested drugs may incorrectly appear to be ineffective or only minimally effective. This is the conclusion of researcher Betty Tijms and colleagues from Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC and Maastricht University. The research results will be published on 9 January in Nature Aging.

In those with Alzheimer's disease, the amyloid and tau protein clump in the brain. In addition to these clumps, other biological processes such as inflammation and nerve ...

Alzheimer Europe adopts position on anti-amyloid therapies for Alzheimer’s disease, issuing a call to action for timely, safe and equitable access

2024-01-09

Luxembourg, 9 January 2024 – In a new position paper, and following engagement with its national members and the European Working Group of People with Dementia (EWGPWD), Alzheimer Europe calls for concrete actions to enable timely, safe and equitable access to anti-amyloid drugs, for patients who are most likely to benefit from these innovative new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

The growing prevalence and impact of AD has catalysed huge investments in research on its causes, diagnosis, treatment and care. After many high-profile ...

Improved cellular recycling could benefit patients with neurodegenerative conditions

2024-01-09

For the first time, a research team at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) has uncovered a way to potentially reduce the amount of toxic cellular waste accumulating in patients with Zellweger Spectrum Disorder (ZSD).

ZSD is a group of rare, neurodegenerative genetic conditions caused by genetic variations that reduce the number of peroxisomes – the parts of cells that are responsible for, among other tasks, breaking down fats. ZSD varies in severity and is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration as well as symptoms that range from visual impairments, such as cataracts, to liver and kidney disfunction.

Like all living ...

Green ammonia could decarbonize 60% of global shipping when offered at just 10 regional fuel ports

2024-01-09

A study published today in IOP Publishing’s journal Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability has found that green ammonia could be used to fulfil the fuel demands of over 60% of global shipping by targeting just the top 10 regional fuel ports. Researchers at the University of Oxford looked at the production costs of ammonia which are similar to very low sulphur fuels, and concluded that the fuel could be a viable option to help decarbonise international shipping by 2050.

Around USD 2 trillion will be needed to transition to a green ammonia fuel supply chain by 2050, primarily to finance ...

Samsung leads again in U.S. patents while Qualcomm leaps into second place; overall grants dip 3.4%

2024-01-09

New Haven, Conn., Jan. 9, 2024—U.S. patent grants declined 3.4% from 2022, the lowest level since 2019, and Samsung held onto the top spot for the second year in a row according to IFI CLAIMS Patent Services, world leader in tracking patent application and grant data.

IFI CLAIMS Patent Services is a Digital Science company that compiles and tracks data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and other patent-issuing agencies around the globe. IFI translates its world-leading data into an annual U.S. Top 50 and IFI Global 250 patent rankings, providing valuable insights into companies’ R&D activity.

Other findings in IFI’s latest rankings include patent powerhouse ...

Severe MS predicted using machine learning

2024-01-09

A combination of only 11 proteins can predict long-term disability outcomes in multiple sclerosis (MS) for different individuals. The identified proteins could be used to tailor treatments to the individual based on the expected severity of the disease. The study, led by researchers at Linköping University in Sweden, has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

“A combination of 11 proteins predicted both short and long-term disease activity and disability outcomes. We also concluded that it’s important to measure ...

Combining anti-tumor drugs with chemo may improve rare children’s cancer outcomes

2024-01-09

Children who develop neuroblastomas, a rare form of cancer which develops in nerve cells, may benefit from receiving certain anti-tumour drugs as well as chemotherapy, a new trial has found.

The results of the BEACON trial conducted by the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Birmingham found that combining anti-angiogenic drugs, which block tumours from forming blood vessels, alongside various chemotherapy drugs led to more young people seeing their tumours shrinking, from 18% in the control group to 26% among those on Bevacizumab.

The findings are published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology today. The trial saw 160 young ...