Novel chemical recycling system for vinyl polymers of cyclic styrene derivatives

Researchers propose a new strategy for obtaining monomer precursors via depolymerization of cyclic α-substituted styrene-based vinyl polymers

2024-01-09

(Press-News.org) Chemical recycling of widely used vinyl polymers (VPs) is one of the key technologies required for realizing a sustainable society. In this regard, a team of researchers from Shinshu University have recently reported a new chemical process that facilitates the depolymerization of cyclic styrene-based VPs, resulting in the recovery of a monomer precursor. This highly efficient chemical recycling system can help with effective resource circulation and the development of new plastic recycling technologies.

Vinyl polymers (VPs) are one of the most widely used plastic materials. They are found everywhere, from poly(vinyl chloride) pipes and surgical gloves to disposable polystyrene plates. Given the global call for a move towards sustainability, would it not be great to chemically recycle this widely used polymer for realizing a sustainable society?

Recently, a team of researchers led by Associate Professor Yasuhiro Kohsaka from the Faculty of Textile Science and Technology (FTST) and Research Initiative for Supra-Materials (RISM), both at Shinshu University, undertook a study to find a way out for achieving this. In their recent breakthrough published online in ACS Macro Letters on 27 November 2023 and co-authored by Yota Chiba from the FTST at Shinshu University, the team presented a new strategy for effectively depolymerizing the VPs of cyclic styrene derivatives to retrieve a monomer precursor.

Traditionally, chemical recycling of VPs has always been challenging. The conventional approach to recycling any polymer is reversing the polymerization process, which entails breaking a single large molecule made up of repeating monomeric units down to its parent monomeric components. Depolymerizing VPs is difficult because the covalent carbon–carbon bonds holding together the monomer units are very stable and therefore tough to break. Studies have proposed ways to break the carbon–carbon backbone of VPs, but most of them fail to ensure quantitative and selective scission (bond breaking) of its main chain, which is crucial to the effective recovery of monomers.

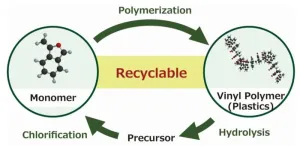

“Polymers that are stable have poor recyclability, and the ones that are easily recyclable are unstable in nature,” says Dr. Kohsaka. “We overcame this trade-off by forgoing conventional strategies that try to reverse the polymerization reaction to recover monomers and developing a two-step recycling process. In the first step, degradation of the polymer to a monomeric precursor was achieved, which was followed by the recovery of the monomer by chemical modification.”

The team chose VPs made of cyclic α-substituted styrene derivatives, such as 3-methylene phthalide, as their molecule for testing chemical recyclability and investigating the ring-opening reaction of the pendant groups in the presence of a base like sodium hydroxide. They found that the opening of the rings due to saponification increased the steric hindrance around the pendant groups, which led to main-chain scission and depolymerization of the VP into monomer precursors. These recovered precursors were then converted to monomers via single-step chlorination and spontaneous intramolecular esterification. The researchers further discovered that the same cyclic monomer structure that facilitated depolymerization was also responsible for promoting polymerization owing to reduced steric hindrance around the vinylidene group. These findings led the researchers to conclude that cyclic α-substituted styrene derivatives have the potential for chemical recycling.

At a broader level, this study has opened new avenues for resource circulation, one of the foundational pillars of a sustainable society, by providing a facile method of polymerization and depolymerization of ubiquitous VPs. The researchers believe that their findings can provide useful fodder for further research on not just the depolymerization of plastic materials but also the development of new recyclable plastics.

“The aim of our research was to aid the mission of developing efficient plastic recycling technology, which is a tool that humanity desperately needs against the backdrop of environmental pollution caused by plastics. While we cannot remove all the plastic that already exists on this planet, we can at least make the best use of plastic resources available to us with our new chemical recycling strategy,” concludes Dr. Kohsaka.

###

About Shinshu University

Shinshu University is a national university founded in 1949 and located nestling under the Japanese Alps in Nagano known for its stunning natural landscapes. Our motto, "Powered by Nature - strengthening our network with society and applying nature to create innovative solutions for a better tomorrow" reflects the mission of fostering promising creative professionals and deepening the collaborative relationship with local communities, which leads to our contribution to regional development by innovation in various fields. We’re working on providing solutions for building a sustainable society through interdisciplinary research fields: material science (carbon, fiber and composites), biomedical science (for intractable diseases and preventive medicine) and mountain science, and aiming to boost research and innovation capability through collaborative projects with distinguished researchers from the world. For more information visit https://www.shinshu-u.ac.jp/english/ or follow us on X (Twitter) @ShinshuUni for our latest news.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-01-09

The quantum Cheshire cat effect draws its name from the fictional Cheshire Cat in the Alice in Wonderland story. That cat was able to disappear, leaving only its grin behind. Similarly, in a 2013 paper, researchers claimed quantum particles are able to separate from their properties, with the properties travelling along paths the particle cannot. They named this the quantum Cheshire cat effect. Researchers since have claimed to extend this further, swapping disembodied properties between particles, disembodying multiple properties simultaneously, ...

2024-01-09

Complimentary press passes are now available for Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB). Join us March 23–26 in San Antonio to experience an engaging agenda showcasing the newest developments and current trends in the field.

As the flagship meeting for one of the largest molecular life science organizations in the world, #DiscoverBMB brings together researchers in academia and industry from across the globe.

Explore captivating science stories and connect with leading experts during the scientific symposia, which will encompass 12 themes. Topics include:

Exciting ...

2024-01-09

Children and adults with rare, deadly genetic diseases have fresh hope for curative therapies, thanks to a new collaboration between the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) and Danaher Corporation, a global life sciences and diagnostics innovator.

The new Danaher-IGI Beacon for CRISPR Cures center will use genome editing to address potentially hundreds of diseases, including rare genetic disorders that have no cure. The goal is to ensure treatments can be developed and brought to patients ...

2024-01-09

DALLAS, Jan. 9, 2024 — A physician-scientist from Massachusetts researching whether chemicals naturally occurring in foods could help treat heart disease, a genetics expert from Pennsylvania exploring the molecular mechanisms of lipid metabolism and cardiovascular diseases and a California-based professor of cardiovascular medicine studying how vaping impacts the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms are the most recent American Heart Association Merit Award recipients. Over the next five years, each researcher will receive a total of $1 million in funding from the Association, the world’s leading voluntary organization focused on heart and brain health and research, ...

2024-01-09

Phages, the viruses that infect bacteria, will pay a high growth-rate cost to access environmental information that can help them choose which lifecycle to pursue, according to a study. Yigal Meir and colleagues developed a model of a bacteria-phage system to investigate how much the viruses should be willing to invest to acquire information about their local environment. A temperate phage, once inside a bacterium, can choose one of two life cycles. In the lytic cycle, the phage turns the bacterium ...

2024-01-09

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Researchers from Binghamton University, State University of New York are unraveling the workings of Group B Strep (GBS) infections in pregnant women, which could someday lead to a vaccine.

One in five pregnant women carry Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Strep or GBS) in the vaginal tract, which is typically harmless — except when it isn’t.

The bacterial infection poses serious and even fatal consequences for newborns, including pneumonia, sepsis and meningitis, which can have long-term effects on the child’s cognitive function.

Researchers ...

2024-01-09

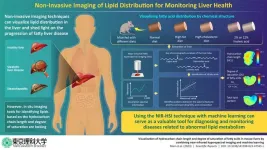

Steatotic liver disease (SLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, which includes a range of conditions caused by fat build-up in the liver due to abnormal lipid metabolism, affects about 25% of the population worldwide, making it the most common liver disorder. Often referred to as “silent liver disease,” SLD progresses without noticeable symptoms and can lead to more severe conditions like cirrhosis (liver scarring) and liver cancer.

A liver biopsy—an invasive procedure involving liver tissue sample extraction from the body—is ...

2024-01-09

Robotics and autonomous vehicles are among the most rapidly growing domains in the technological landscape, with the potential to make work and transportation safer and more efficient. Since both robots and self-driving cars need to accurately perceive their surroundings, 3D object detection methods are an active area of study. Most 3D object detection methods employ LiDAR sensors to create 3D point clouds of their environment. Simply put, LiDAR sensors use laser beams to rapidly scan and measure the ...

2024-01-09

Levi Gadye, 628-399-1046

Levi.Gadye@ucsf.edu | @UCSF

Video: https://ucsf.app.box.com/s/i3atd54ye4m1z1spi0qf59axq7tq7640

Subscribe to UCSF News

A high-sugar diet is bad news for humans, leading to diabetes, obesity and even cancer. Yet fruit bats survive and even thrive by eating up to twice their body weight in sugary fruit every day.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have discovered how fruit bats may have evolved to consume so much sugar, with potential implications for the 37 million Americans with diabetes. The findings, published on Tuesday, Jan. 9, 2024 in Nature Communications, point to adaptations ...

2024-01-09

HOUSTON ― A vaccine showed potential to prevent relapse of KRAS-mutated pancreatic and colorectal cancers for patients who had previously undergone surgery, according to a Phase I trial led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Results were published today in Nature Medicine.

In the trial, patients with pancreatic and colorectal cancer who were considered at high risk of relapse received a maximum of 10 doses of the ELI-002 vaccine targeted toward KRAS G12D and G12R mutations. T cell responses were seen in 84% of all patients and in 100% of those in the two highest dose cohorts, including those who ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Novel chemical recycling system for vinyl polymers of cyclic styrene derivatives

Researchers propose a new strategy for obtaining monomer precursors via depolymerization of cyclic α-substituted styrene-based vinyl polymers