(Press-News.org) Australia is known for its wonderous and unique wildlife. But, just like the rest of the world, Australia is expected to get even hotter because of climate change. This could spell disaster for many of the marsupials that call the drier regions of the country home as it may get too hot for them to handle. To make things even more difficult, many of these marsupials are endangered thanks to habitat loss and introduced species such as domestic cats and red foxes. Therefore, finding a way to study these animals without disturbing them is critical to ensure their survival. This realisation led Christine Cooper (Curtin University, Australia) and Philip Withers (University of Western Australia) to use infrared cameras and computer models to figure out how hot it can get before the numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) can’t take the heat. They publish their finding in Journal of Experimental Biology that high air and ground temperatures limit how long numbats can forage in the sun to ~10 minutes, after which the numbats have to retreat to the shade. Under even more extreme conditions, high temperatures of their surroundings along with the heat radiating from objects in the environment and the humidity may threaten numbat survival even in the shade.

Cooper and Withers drove around the forest paths of two Western Australian wheatbelt reserves – Dryandra Woodland and Boyagin Nature Reserve – during 2020 and 2021 to film ~50 numbats using their infrared camera. While doing this, the researchers also used a portable weather station to measure the air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation and wind speed, which they combined to get a measure of the true environmental temperature. Numbats are the only marsupials that are solely active during the day. In fact, the team found the marsupials are in the sun 62% of the time. So, what does being in the sun do to the numbats’ temperature?

Cooper and Withers measured the surface temperatures of different areas of the numbat’s body when the numbats were in the sun and in the shade. Unsurprisingly, the researchers found that direct sunlight made the numbats gain heat quickly. But being in direct sunlight only accounted for 18% of the heat that the numbats gained, so the numbats must be gaining heat from elsewhere. In fact, the numbats that tried to cool off by retreating to the shade at high temperatures were still gaining heat, despite being out of the direct sun. This led the researchers to conclude that heat from the air and ground, along with the heat radiating from objects in their environment, are the main sources of heat contributing to a numbat’s risk of overheating. Because of this, the team concluded that soon, even the shade will be too hot to help numbats to keep cool.

Cooper and Withers next calculated how long the numbats could search for their food before their body temperature warmed up to 40°C (the hottest body temperature recorded for an active numbat). The team found that if the air and ground temperatures (not the temperature in direct sunlight) increased to 23°C, the numbats were only able to remain in the sun for 10 minutes before their body temperature reached 40°C. This poses a huge problem for the numbats as their only food source is termites. Termites aren’t very nutritious, so numbats have to eat large numbers of them to survive. Termites live deep underground and only move toward the surface once the ground warms up during the day. This means numbats can only feed in daytime, when the sun has warmed the ground enough for the insects to be close to the surface, within easy reach.

Thanks to climate change, the future for numbats is looking bleak. They can’t forage at night to when the temperature drops because their food will be too far underground for them to reach and they will be vulnerable to predators, nor can they survive in the shade if the climate keeps warming as predicted, because of increasing heat stored in the air and rocks. Something must be done to stop the rise in global temperatures or one of Australia’s iconic marsupials could become another tragic example of a creature we could have saved.

*****************************************

IF REPORTING THIS STORY, PLEASE MENTION JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY AS THE SOURCE AND, IF REPORTING ONLINE, PLEASE CARRY A LINK TO: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article-lookup/doi/10.1242/jeb.246301

REFERENCE: Cooper, C. E. and Withers, P. C. (2023) Implications of heat exchange for a free-living endangered marsupial determined by non-invasive thermal imaging. J. Exp. Biol. 226, jeb 246301. doi: 10.1242/jeb.246301

DOI:10.1242/jeb.246301

This article is posted on this site to give advance access to other authorised media who may wish to report on this story. Full attribution is required and if reporting online a link to https://journals.biologists.com/jeb is also required. The story posted here is COPYRIGHTED. Advance permission is required before any and every reproduction of each article in full from permissions@biologists.com.

THIS ARTICLE IS EMBARGOED UNTIL THURSDAY, 11 JANUARY 2024, 13:00 HRS EST (18:00 HRS GMT)

END

Embargoed for release until 1:00 p.m. ET on Thursday 11 January 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find a summary for new article that will be published in of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summary is not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

-------------------------------------------------

ACIP ...

Curtin University research using thermal imaging of numbats in Western Australia has found that during hot weather the endangered animals are limited to as little as ten minutes of activity in the sun before they overheat to a body temperature of greater than 40°C.

Lead author Dr Christine Cooper, from Curtin’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences, said despite using techniques such as raising or flattening their fur to regulate body temperature, numbats were prone to overheating, which was an important consideration for future conservation efforts, particularly given our warming climate.

“Active only during ...

In an editorial in the Annals of Internal Medicine, CUNY SPH Distinguished Lecturer Scott Ratzan, Senior Scholar Ken Rabin, and colleagues call for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to “raise its persuasive communications game” on adult immunization to clinicians and the public. They argue that disseminating scientific information alone will not suffice in the present environment of disinformation and low trust in public health.

The editorial is in response to the CDC’s ...

JMIR Publications is pleased to announce that JMIR Biomedical Engineering has passed the Scientific Quality Review by the US National Library of Medicine (NLM) for PubMed Central (PMC). This decision reflects the scientific and editorial quality of the journal. All articles published from 2021 onward will be found on PMC and PubMed after their technical evaluation.

Launched in 2016, JMIR Biomedical Engineering is a sister journal of Journal of Medical Internet Research (the leading open-access journal in health informatics), focused on the application of engineering principles, ...

At the center of most large galaxies lives a supermassive black hole (SMBH). The Milky Way has Sagittarius A*, a mostly dormant SMBH whose mass is around 4.3 million times that of the sun. But if you look deeper into the universe, there are vastly larger SMBHs with masses that can reach up to tens of billions of times the mass of our sun.

Black holes grow in mass by gravitationally consuming objects in their near vicinity, including stars. It’s a catastrophic and destructive end for stars unlucky enough to be swallowed by SMBHs, but fortunate for scientists who now have an opportunity to probe otherwise-dormant centers of galaxies.

TDEs Light the Way

As the name ...

A new study sheds light on how autophagy, the body’s process for removing damaged cell parts, when impaired, can play a role in causing heart failure. The research team led by Dr. E. Dale Abel, chair of the Department of Medicine at UCLA and Dr. Quanjiang Zhang, adjunct assistant professor of medicine at UCLA, identified a signaling pathway that links autophagy to the control of cellular levels of a key coenzyme known as NAD+, which is found in all living cells and is central to how our metabolism works. Researchers say these findings may have implications ...

Phytoplankton or microalgae found in the ocean are often known to produce a sulfur-containing chemical called dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). This organic molecule breaks down to release a strong but sweet-smelling gas called dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which plays a major role in the formation of cloud condensation nuclei and is also associated with the smell of the sea. More importantly, DMSP acts as an osmolyte and thus protects the phytoplankton against the osmotic pressure created by saline water.

Scientists have, however, ...

A team of astronomers including those from the University of Tokyo created the first-ever map of magnetic field structures within a spiral arm of our Milky Way galaxy. Previous studies on galactic magnetic fields only gave a very general picture, but the new study reveals that magnetic fields in the spiral arms of our galaxy break away from this general picture significantly and are tilted away from the galactic average by a high degree. The findings suggest magnetic fields strongly impact star-forming regions which means they played a part in the creation of our own solar system.

It might come as a surprise to ...

Researchers have identified a 3D fragment of fossilized skin that is at least 21 million years than previously described skin fossils. The skin, which belonged to an early species of Paleozoic reptile, has a pebbled surface and most closely resembles crocodile skin. It’s the oldest example of preserved epidermis, the outermost layer of skin in terrestrial reptiles, birds, and mammals, which was an important evolutionary adaptation in the transition to life on land. The fossil is described on January 11 in the journal Current Biology along with several other specimens that were collected from the Richards Spur ...

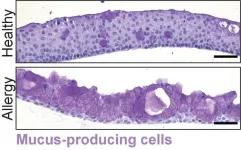

The Organoid group at the Hubrecht Institute produced the first organoid model of the human conjunctiva. These organoids mimic the function of the actual human conjunctiva, a tissue involved in tear production. Using their new model, the researchers discovered a new cell type in this tissue: tuft cells. The tuft cells become more abundant under allergy-like conditions and are therefore likely to play a role in allergies. The organoid model can now be used to test drugs for several diseases affecting the conjunctiva. The study will be published in Cell Stem Cell on 11 January 2024.

Our eyes produce tears to protect themselves from injuries and ...