Oldest known fossilized skin is 21 million years older than previous examples

2024-01-11

(Press-News.org) Researchers have identified a 3D fragment of fossilized skin that is at least 21 million years than previously described skin fossils. The skin, which belonged to an early species of Paleozoic reptile, has a pebbled surface and most closely resembles crocodile skin. It’s the oldest example of preserved epidermis, the outermost layer of skin in terrestrial reptiles, birds, and mammals, which was an important evolutionary adaptation in the transition to life on land. The fossil is described on January 11 in the journal Current Biology along with several other specimens that were collected from the Richards Spur limestone cave system in Oklahoma.

“Every now and then we get an exceptional opportunity to glimpse back into deep time,” says first author Ethan Mooney, a paleontology graduate student at the University of Toronto who worked on the project as an undergraduate with paleontologist Robert Reisz at the University of Toronto. “These types of discoveries can really enrich our understanding and perception of these pioneering animals.”

Skin and other soft tissues are rarely fossilized, but the researchers think that skin preservation was possible in this case because of the cave system’s unique features, which included fine clay sediments that slowed decomposition, oil seepage, and a cave environment that was likely an oxygenless environment.

“Animals would have fallen into this cave system during the early Permian and been buried in very fine clay sediments that delayed the decay process,” says Mooney. “But the kicker is that this cave system was also an active oil seepage site during the Permian, and interactions between hydrocarbons in petroleum and tar are likely what allowed this skin to be preserved.”

The skin fossil is tiny—smaller than a fingernail. Microscopic examination undertaken by coauthor Tea Maho of the University of Toronto Mississauga revealed epidermal tissues, a hallmark of the skin of amniotes, the terrestrial vertebrate group that includes reptiles, birds, and mammals and which evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous Period. “We were totally shocked by what we saw because it’s completely unlike anything we would have expected,” says Mooney. “Finding such an old skin fossil is an exceptional opportunity to peer into the past and see what the skin of some of these earliest animals may have looked like.”

The skin shares features with ancient and extant reptiles, including a pebbled surface similar to crocodile skin, and hinged regions between epidermal scales that resemble skin structures in snakes and worm lizards. However, because the skin fossil is not associated with a skeleton or any other remains, it is not possible to identify what species of animal or body region the skin belonged to.

The fact that this ancient skin resembles the skin of reptiles alive today shows how important these structures are for survival in terrestrial environments. “The epidermis was a critical feature for vertebrate survival on land,” says Mooney. “It's a crucial barrier between the internal body processes and the harsh outer environment.”

The researchers say that this skin may represent the ancestral skin structure for terrestrial vertebrates in early amniotes that allowed for the eventual evolution of bird feathers and mammalian hair follicles.

The skin fossil and other specimens were collected by lifelong paleontology enthusiasts Bill and Julie May at Richards Spur, a limestone cave system in Oklahoma that is an active quarry. The unique conditions at Richards Spur preserved many of the oldest examples of early terrestrial animals. The specimens are housed at the Royal Ontario Museum.

###

This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and Jilin University.

Current Biology, Mooney et al., “Paleozoic Cave System Preserves Oldest Known Evidence of Amniote Skin” https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(23)01663-9

Current Biology (@CurrentBiology), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. Visit http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-01-11

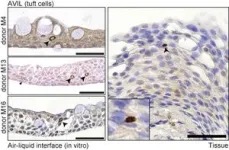

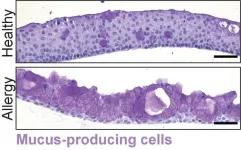

The Organoid group at the Hubrecht Institute produced the first organoid model of the human conjunctiva. These organoids mimic the function of the actual human conjunctiva, a tissue involved in tear production. Using their new model, the researchers discovered a new cell type in this tissue: tuft cells. The tuft cells become more abundant under allergy-like conditions and are therefore likely to play a role in allergies. The organoid model can now be used to test drugs for several diseases affecting the conjunctiva. The study will be published in Cell Stem Cell on 11 January 2024.

Our eyes produce tears to protect themselves from injuries and ...

2024-01-11

A new species of tyrannosaur from southern North America that may the closest known relative of Tyrannosaurus rex is described in a study published in Scientific Reports.

Sebastian Dalman and colleagues identified the new species — which they have named Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis — by examining a fossilised partial skull, which was previously discovered in the Hall Lake Formation, New Mexico, USA. Although these remains were initially assigned to T. rex and are comparable in size to those of T. rex (which was up to 12 metres long), the authors propose that they belong to a new species due ...

2024-01-11

MIAMI, FLORIDA (EMBARGOED UNTIL JAN. 11, 2024, at 11 AM EST) – Certain cancers are more difficult to treat because they contain cells that are highly skilled at evading drugs or our immune systems by disguising themselves as healthy cells.

Glioblastoma, for example, an incurable brain cancer, is characterized by cells that can mimic human neurons, even growing axons and making active connections with healthy brain neurons. This cancer is usually deadly – average survival time is just over one year from diagnosis ...

2024-01-11

A new study led by researchers from the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center shows that using high doses of radiation while integrating an ablative radiotherapy technique called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) concurrently with chemotherapy is safe and effective in treating people with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer that is not suitable for surgery.

Based on mid-treatment response, researchers found the combination treatment, which involves a second radiation plan to personalize a boost for the last third of radiation treatments, is a viable and promising option that helps reduce the risk of toxic side effects and having the cancer ...

2024-01-11

Whether picking up a small object like a pen or coordinating different body parts, the cerebellum in the brain performs essential functions for controlling our movement. Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) investigated how a crucial set of synapses between neurons within it functions and develops. Their findings have now been published in the journal Neuron.

Even if you do not think about it, every day you are using the intricate circuits of neurons in your brain to perform astonishingly delicate movements with your body. One essential unit in this is the cerebellum playing a key role in fine motor control, coordination, and timing.

“Every ...

2024-01-11

UPTON, NY—Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Columbia University have developed a way to convert carbon dioxide (CO2), a potent greenhouse gas, into carbon nanofibers, materials with a wide range of unique properties and many potential long-term uses. Their strategy uses tandem electrochemical and thermochemical reactions run at relatively low temperatures and ambient pressure. As the scientists describe in the journal Nature Catalysis, this approach could successfully lock carbon away in a useful solid form to offset or even achieve negative carbon emissions.

“You can put the carbon nanofibers ...

2024-01-11

About The Study: The findings of this study of 6,101 adult cancer survivors suggest that substance use disorder (SUD) prevalence is higher among survivors of certain types of cancer; this information could be used to identify cancer survivors who may benefit from integrated cancer and SUD care. Future efforts to understand and address the needs of adult cancer survivors with comorbid SUD should prioritize cancer populations in which SUD prevalence is high.

Authors: Devon K. Check, Ph.D., of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, is the corresponding author.

To access the ...

2024-01-11

About The Study: In this study of patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer from 2017 to 2020 in the U.S., the incidence of localized head and neck cancer declined during the first year of the pandemic. A subsequent increase in advanced-stage diagnoses may be observed in later years.

Authors: Nosayaba (Nosa) Osazuwa-Peters, B.D.S., Ph.D., M.P.H., C.H.E.S., of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

2024-01-11

A new, systematic analysis of cancer cells identifies 370 candidate priority drug targets across 27 cancer types, including breast, lung and ovarian cancers.

By looking at multiple layers of functional and genomic information, researchers were able to create an unbiased, panoramic view of what enables cancer cells to grow and survive. They identify new opportunities for cancer therapies in a significant leap towards a new generation of smarter, more effective cancer treatments.

In the most comprehensive study of its kind, researchers ...

2024-01-11

AI language models are booming. The current frontrunner is ChatGPT, which can do everything from taking a bar exam, to creating an HR policy, to writing a movie script.

But it and other models still can’t reason like a human. In this Q&A, Dr. Vered Shwartz (she/her), assistant professor in the UBC department of computer science, and masters student Mehar Bhatia (she/her) explain why reasoning could be the next step in AI—and why it’s important to train these models using diverse ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Oldest known fossilized skin is 21 million years older than previous examples