(Press-News.org) A new study by physicists and neuroscientists from the University of Chicago, Harvard and Yale describes how connectivity among neurons comes about through general principles of networking and self-organization, rather than the biological features of an individual organism.

The research, published on January 17, 2024 in Nature Physics, accurately describes neuronal connectivity in a variety of model organisms and could apply to non-biological networks like social interactions as well.

“When you’re building simple models to explain biological data, you expect to get a good rough cut that fits some but not all scenarios,” said Stephanie Palmer, PhD, Associate Professor of Physics and Organismal Biology and Anatomy at UChicago and senior author of the paper. “You don’t expect it to work as well when you dig into the minutiae, but when we did that here, it ended up explaining things in a way that was really satisfying.”

Understanding how neurons connect

Neurons form an intricate web of connections between synapses to communicate and interact with each other. While the vast number of connections may seem random, networks of brain cells tend to be dominated by a small number of connections that are much stronger than most.

This “heavy-tailed” distribution of connections (so-called because of the way it looks when plotted on a graph) forms the backbone of circuitry that allows organisms to think, learn, communicate and move. Despite the importance of these strong connections, scientists were unsure if this heavy-tailed pattern arises because of biological processes specific to different organisms, or due to basic principles of network organization.

To answer these questions, Palmer and Christopher Lynn, PhD, Assistant Professor of Physics at Yale University, and Caroline Holmes, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University, analyzed connectomes, or maps of brain cell connections. The connectome data came from several different classic lab animals, including fruit flies, roundworms, marine worms and the mouse retina.

To understand how neurons form connections to one another, they developed a model based on Hebbian dynamics, a term coined by Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb in 1949 that essentially says, “neurons that fire together, wire together.” This means the more two neurons activate together, the stronger their connection becomes.

Across the board, the researchers found these Hebbian dynamics produce “heavy-tailed” connection strengths just like they saw in the different organisms. The results indicate that this kind of organization arises from general principles of networking, rather than something specific to the biology of fruit flies, mice, or worms.

The model also provided an unexpected explanation for another networking phenomenon called clustering, which describes the tendency of cells to link with other cells via connections they share. A good example of clustering occurs in social situations. If one person introduces a friend to a third person, those two people are more likely to become friends with them than if they met separately.

"These are mechanisms that everybody agrees are fundamentally going to happen in neuroscience,” Holmes said. “But we see here that if you treat the data carefully and quantitatively, it can give rise to all of these different effects in clustering and distributions, and then you see those things across all of these different organisms.”

Accounting for randomness

As Palmer pointed out, though, biology doesn’t always fit a neat and tidy explanation, and there is still plenty of randomness and noise involved in brain circuits. Neurons sometimes disconnect and rewire with each other — weak connections are pruned, and stronger connections can be formed elsewhere. This randomness provides a check on the kind of Hebbian organization the researchers found in this data, without which strong connections would grow to dominate the network.

The researchers tweaked their model to account for randomness, which improved its accuracy.

“Without that noise aspect, the model would fail,” Lynn said. “It wouldn’t produce anything that worked, which was surprising to us. It turns out you actually need to balance the Hebbian snowball effect with the randomness to get everything to look like real brains.”

Since these rules arise from general networking principles, the team hopes they can extend this work beyond the brain.

“That’s another cool aspect of this work: the way the science got done,” Palmer said. “The folks on this team have a huge diversity of knowledge, from theoretical physics and big data analysis to biochemical and evolutionary networks. We were focused on the brain here, but now we can talk about other types of networks in future work.”

The study, “Heavy–tailed neuronal connectivity arises from Hebbian self–organization,” was supported by the National Science Foundation, through the Center for the Physics of Biological Function (PHY–1734030) and a Graduate Research Fellowship (C.M.H.); by the James S. McDonnell Foundation through a Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (C.W.L.); and by the National Institutes of Health BRAIN initiative (R01EB026943).

END

Surprisingly simple model explains how brain cells organize and connect

Scientists from UChicago, Harvard, and Yale propose a self-organizing model of connectivity that applies across a wide range of organisms and potentially other types of networks as well.

2024-01-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Transforming clinical recording of deep brain activity with a new take on sensor manufacturing

2024-01-17

Sensors built with a new manufacturing approach are capable of recording activity deep within the brain from large populations of individual neurons–with a resolution of as few as one or two neurons–in humans as well as a range of animal models, according to a study published in the Jan. 17, 2024 issue of the journal Nature Communications. The research team is led by the Integrated Electronics and Biointerfaces Laboratory (IEBL) at the University of California San Diego.

The approach is unique in several ways. It relies on ultra-thin, flexible and customizable probes, made of clinical-grade materials, and equipped with sensors that can record extremely localized ...

Role of inherited genetic variants in rare blood cancer uncovered

2024-01-17

Large-scale genetic analysis has helped researchers uncover the interplay between cancer-driving genetic mutations and inherited genetic variants in a rare type of blood cancer.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge, and collaborators, combined various comprehensive data sets to understand the impact of both cancer-driving spontaneous mutations and inherited genetic variation on the risk of developing myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN).

The study, published today (17 January) in Nature Genetics, describes how inherited genetic variants can influence whether a spontaneous mutation in a particular ...

AI model predicts death, complications for patients undergoing angioplasty, stents

2024-01-17

When a person has one or more blocked arteries, providers may choose to conduct a minimally invasive procedure known as percutaneous coronary intervention, or PCI.

By inflating a balloon and potentially placing a stent, blood can flow more freely from the heart.

Despite carrying less risk than open surgery, stenting and balloon angioplasty can result in complications like bleeding and kidney injury.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine developed an AI-driven algorithm that accurately predicts death and complications after PCI — which could emerge as a tool ...

E-cigarettes help pregnant smokers quit without risks to pregnancy

2024-01-17

A new analysis of trial data on pregnant smokers, led by researchers at Queen Mary University of London, finds that the regular use of nicotine replacement products during pregnancy is not associated with adverse pregnancy events or poor pregnancy outcomes.

The PREP 2 study used data collected from over 1100 pregnant smokers attending 23 hospitals in England and 1 stop-smoking service in Scotland to compare pregnancy outcomes in women who did or did not use nicotine in the form of e-cigarettes (EC) or nicotine patches ...

John Innes Centre researcher honored with prestigious Blavatnik award

2024-01-17

The pioneering research of Dr Yiliang Ding investigating the structure and function of RNA in living cells has been recognised with a major award.

Yiliang a group leader at the John Innes Centre, is among nine recipients of the 2024 Blavatnik Awards for Young Scientists in the UK, announced today by the Blavatnik Family Foundation and The New York Academy of Sciences.

The awards recognise research that is transforming medicine, technology, and our understanding of the world across three categories: Chemical Sciences, Physical Sciences & Engineering, and ...

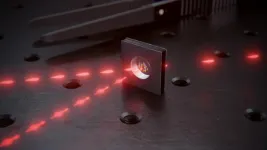

Mass-producible miniature quantum memory

2024-01-17

Researchers at the University of Basel have built a quantum memory element based on atoms in a tiny glass cell. In the future, such quantum memories could be mass-produced on a wafer.

It is hard to imagine our lives without networks such as the internet or mobile phone networks. In the future, similar networks are planned for quantum technologies that will enable the tap-proof transmission of messages using quantum cryptography and make it possible to connect quantum computers to each other.

Like their conventional counterparts, such quantum networks require memory elements in which information can be temporarily stored ...

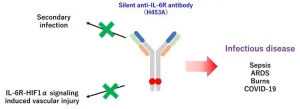

A new targeted treatment calms the cytokine storm

2024-01-17

Osaka, Japan – Cytokines are chemical messengers that help the body get rid of invading bacteria and viruses, and control inflammation. The body carefully balances cytokines because they help keep the immune system healthy. However, this balance is upset if the immune system overreacts. A serious infection or a severe burn can unleash a cytokine storm in the body. During the storm—also called cytokine release syndrome (CRS)—the body produces too many cytokines, leading to life-threatening inflammation.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a key cytokine in the storm because it helps to drive the inflammation that damages ...

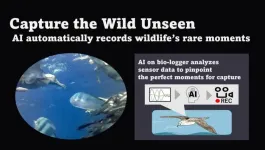

Tiny AI-based bio-loggers revealing the interesting bits of a bird’s day

2024-01-17

Osaka, Japan – Have you ever wondered what wildlife animals do all day? Documentaries offer a glimpse into their lives, but animals under the watchful eye do not do anything interesting. The true essence of their behaviors remains elusive. Now, researchers from Japan have developed a camera that allows us to capture these behaviors.

In a study recently published in PNAS Nexus, researchers from Osaka University have created a small sensor-based data logger (called a bio-logger) that automatically detects and records video of infrequent behaviors in wild seabirds without supervision by researchers.

Infrequent behaviors, such as diving into the water for food, can ...

SDG-washing found among Canada's top companies

2024-01-17

Canada's biggest companies often speak of their plans to be more sustainable, but a new study found corporations aren't fully backing up those commitments.

A team of University of Waterloo researchers concluded that corporate investing in communities fell despite an increase in companies committing to the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) over the last decade.

Researchers investigated the community investment of Canada's 58 leading private-sector companies as a percentage of their net profit after tax to determine whether introducing SDGs created ...

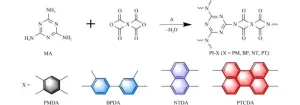

Enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting with a donor-acceptor polyimide

2024-01-17

Polyimide (PI) has emerged as a promising organic photocatalyst owing to its distinct advantages of high visible-light response, facile synthesis, molecularly tunable donor-acceptor structure, and excellent physicochemical stability. However, the synthesis of high-quality PI photoelectrode remains a challenge, and photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting for PI has been less studied.

A research group of Huiyan Zhang and Sheng Chu from Southeast University prepared PI films by a ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

[Press-News.org] Surprisingly simple model explains how brain cells organize and connectScientists from UChicago, Harvard, and Yale propose a self-organizing model of connectivity that applies across a wide range of organisms and potentially other types of networks as well.