(Press-News.org) Halfway through a true crime podcast, a morning commuter jerks the wheel to narrowly avoid a collision. When discussing the podcast with a coworker later that day, the driver can easily recall the details of the episode’s second half but retains only a blurry recollection of how it began.

A new study from psychologists at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology suggests that we remember the moments immediately following a distressing episode more sharply than the moments leading up to it. Clarifying the relationship between trauma and memory can improve how we evaluate eyewitness testimonies, inform therapies to treat PTSD, and help clinicians combat memory decline in brain disorders like Alzheimer’s disease.

This study appears in the journal Cognition and Emotion.

“It’s a clean finding, and it opens up an entirely new dimension for understanding emotion’s impacts on memory,” said lead author Paul Bogdan, whose Ph.D. research at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign formed the basis for this study.

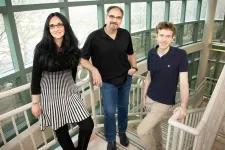

Bogdan’s research was conducted within the Dolcos Lab headed by psychology professors Florin Dolcos and Sanda Dolcos. For more than 15 years, the Dolcoses have studied the relationship between mental health and memory — specifically, unwanted memories that intrude into our daily lives, degrading mental health and aggravating anxiety, depression, and PTSD. The result of their research is an emotional security system, crafted with cognitive therapies that protect emotional security and preserve focus in the face of troublesome recollections.

Studying traumatic memories is tricky, the researchers say, because our brains tend to auto-edit negative experiences. Big ideas trump details, peripheral features concede to central ones, and specific moments are cut loose from their context: the where, when, and “what else,” Florin Dolcos said.

So far, there is little evidence to explain how negative emotion impacts the when: our ability to situate a sequence of memories along a timeline.

“Suppose your partner unexpectedly insults you in the middle of an otherwise neutral discussion. Later, when you are trying to make sense of the encounter …, will you more accurately remember what happened before or after the insult?” Bogdan said. “Existing research does not give us a clear answer.”

But Bogdan’s new research might. His team orchestrated two identical experiments: an initial study of 72 participants to pin down their procedures and predictions, and a replication study with 150 participants to confirm the results.

First, participants viewed a series of images simulating a string of memories. Half of the images elicited negative emotional responses, and half were emotionally neutral. To contextualize the images — and make them more memory-like — the participants were asked to privately imagine themselves traveling among the locations pictured and to craft a creative story arc to bind them together. This “promoted the feeling that pairs of sequential images are meaningfully related,” the researchers wrote.

An hour later, participants viewed pairs of images from the series. For each pair, they were asked whether the second picture occurred immediately before or immediately after the first. (They were also offered a “neither” option and could indicate if they did not remember the order.)

Results were consistent across both studies. The participants’ ability to accurately place the second image improved when the negative memories occurred before the neutral ones on the timeline. If participants were shown a negative image first, they did a better job of recalling neutral images that followed it; inversely, if participants were first shown a neutral image, they could more consistently place the negative images that came before.

In other words, memory flows from negative to neutral.

“So, our results suggest that if insulted in a conversation, one would better retrieve what was said immediately afterward than what was said immediately beforehand,” Bogdan said.

This is unintuitive, the researchers say.

“You might imagine that humans evolved to have a good memory for what led to negative things,” Bogdan said. “If you got bit by a snake, what foolhardy thing were you doing beforehand?”

One explanation is that negative emotional spikes (for example, upon sustaining a snake bite) cause a rush of focus and alertness, telling our brains to take exhaustive notes about what happens next and squirrel them away for future use.

But the prelude to trauma employs a much less diligent notetaker. This casts a dubious eye on scenarios like witness testimonies, where contextual details are paramount.

“Knowing that people are more likely to miss details leading to something negative that happened, we can be more cautious about statements related to events that have led to a crime, compared to memories of what happened after, which we know will be sharper,” Florin Dolcos said.

As relevant in a clinic as it is in a courtroom, these results help clarify the mechanisms behind PTSD, where an objectively neutral activity can trigger an involuntary surge of negative emotions.

“For example, a war veteran hearing a loud noise and inferring that their building will soon collapse due to an explosion,” Florin Dolcos said. “This happens because there is a rupture between the memory of the traumatic experience and its original context: the what breaks from the where and the when.”

Taking back control over traumatic memories, then, requires reattaching them to their context — their original place and time. The researchers hope to incorporate this strategy into cognitive therapies for people with PTSD.

In addition to muting the maelstrom of negative memories, another therapeutic avenue may entail using positive emotions to reconstruct sturdier, sharper memories for those who need them, according to Sanda Dolcos.

“As people age, problems with memories become more serious, especially conditions like Alzheimer’s,” she said. “The memory for context suffers the most. If we know exactly what’s happening, we can build future strategies to better encode information that will help us help others with those conditions.”

Editor’s note

The paper titled “Emotional dissociations in temporal associations: opposing effects of arousal on memory for details surrounding unpleasant events” is available online here: https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2270196

For full author information, please consult the publication.

Bogdan recently defended his Ph.D. thesis and will soon begin a postdoctoral research position at Duke University. Florin Dolcos is also a professor of biomedical and translational sciences, and both Florin and Sanda Dolcos are affiliates of the Center for Social and Behavioral Science.

END

Don’t look back: The aftermath of a distressing event is more memorable than the lead-up, study suggests

The moments that follow a distressing episode are more memorable than the moments leading up to it.

2024-01-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

FIFA World Cup ends with win for Argentina and COVID-19, new research finds

2024-01-18

TORONTO, Jan. 18, 2024 – The 2022 FIFA World Cup ended with a tight win for Argentina over France on penalties, but it was also a triumph for SARS-CoV-2 with a significant jump in the number of cases, some of which York University researchers say could have been prevented.

New research published today and led by York used the 2022 FIFA World Cup as a case study to help determine the best ways to mitigate virus spread and hospitalizations at mass gatherings in the future. A technique was used ...

New PET/CT technique accurately diagnoses adrenal gland disorder, informs personalized treatment plans

2024-01-18

Reston, VA—A novel imaging approach, 68Ga-pentixafor PET/CT, has been shown to accurately identify sub-types of primary aldosteronism (an adrenal gland disorder), outperforming traditional methods for diagnosis. Reported in the January issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine, this detailed imaging technique provides a clearer picture of the adrenal glands, helping doctors decide more confidently whether surgery is the right option for patients.

Primary aldosteronism is an endocrine disorder that occurs when the adrenal glands produce too much of the hormone aldosterone, frequently ...

A window into plant evolution: The unusual genetic journey of lycophytes

2024-01-18

An international team of researchers has uncovered a remarkable genetic phenomenon in lycophytes, which are similar to ferns and among the oldest land plants. Their study, recently published in the journal PNAS, reveals that these plants have maintained a consistent genetic structure for over 350 million years, a significant deviation from the norm in plant genetics.

"The exceptionally slow pace of genomic evolution sets these plants apart," said Dr. Fay-Wei Li, a professor at the Boyce Thompson Institute and a senior author of the study. ...

Climate change linked to spread of diarrheal illness

2024-01-18

Temperature, day length and humidity have been found to be linked to the increased spread of a diarrhoeal illness a new study from the University of Surrey reveals. The findings could help predict further outbreaks of the illness, potentially leading to better preparedness within health services.

During this unique study, researchers led by Dr Giovanni Lo Iacono, investigated the impact of weather on the transmission of campylobacteriosis, a bacterial infection which can cause diarrhoea and stomach pains. According to the World Health Organisation, Campylobacter infections are the most common causes of human bacterial gastroenteritis in the world. Infections are generally ...

Injectable agents could improve liquid biopsy for cancer detection and monitoring

2024-01-18

Scientists have developed two agents, made of therapeutic nanoparticles and antibodies, that could be given to patients shortly before a blood draw to allow physicians to better detect tumor DNA in blood using a technology called liquid biopsy.

Liquid biopsies promise to transform how cancers are diagnosed, monitored, and treated by detecting DNA that tumors shed into the blood. But the body presents a significant challenge. Immune cells in the liver and DNA-degrading enzymes in blood remove circulating tumor DNA from the bloodstream within minutes, making this DNA difficult to capture and detect in a blood test.

To overcome this, a team from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard ...

A fungal pathogen, Rosellinia necatrix, that attacks plants, produces antimicrobials to combat the plant-hosted bacteria that would otherwise inhibit its infection success

2024-01-18

A fungal pathogen, Rosellinia necatrix, that attacks plants, produces antimicrobials to combat the plant-hosted bacteria that would otherwise inhibit its infection success.

####

Article Title: The soil-borne white root rot pathogen Rosellinia necatrix expresses antimicrobial proteins during host colonization

Article URL: http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1011866

Author Countries: Germany, Spain, the Netherlands

Funding: EACC and DET acknowledge receipt of PhD fellowships from CONACyT, Mexico. ALM is holder of a postdoctoral research fellow funded by the 'Fundación Ramón Areces'. BPHJT ...

Researchers improve blood tests’ ability to detect and monitor cancer

2024-01-18

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Tumors constantly shed DNA from dying cells, which briefly circulates in the patient’s bloodstream before it is quickly broken down. Many companies have created blood tests that can pick out this tumor DNA, potentially helping doctors diagnose or monitor cancer or choose a treatment.

The amount of tumor DNA circulating at any given time, however, is extremely small, so it has been challenging to develop tests sensitive enough to pick up that tiny signal. A team of researchers from MIT and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has now come up with a way to significantly boost that signal, by temporarily slowing the clearance of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream.

The ...

Sea otters may be key drivers of changes in California's kelp forests, according to data spanning a century

2024-01-18

Sea otters may be key drivers of changes in California's kelp forests, according to data spanning a century

#####

In your coverage please use this URL to provide access to the freely available article in PLOS Climate: https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000290

Article Title: Sea otter recovery buffers century-scale declines in California kelp forests

Citation: Nicholson TE, McClenachan L, Tanaka KR, Van Houtan KS (2024) Sea otter recovery buffers century-scale declines in California ...

Norovirus outbreaks are detectable by wastewater monitoring earlier than by other surveillance methods depending on reporting practices, making this a potentially important public health tool

2024-01-18

Norovirus outbreaks are detectable by wastewater monitoring earlier than by other surveillance methods depending on reporting practices, making this a potentially important public health tool.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/water/article?id=10.1371/journal.pwat.0000198

Article Title: Norovirus GII wastewater monitoring for epidemiological surveillance

Author Countries: USA

Funding: This study was supported by funding from the University of Michigan through the Public Health Infection ...

Climate change may reduce life expectancy by half a year, study suggests

2024-01-18

The cost of climate change may be six months off the average human lifespan, according to a study published January 18, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS Climate by Amit Roy from Shahjalal University of Science and Technology and The New School for Social Research, U.S.

Temperature and rainfall — two telltale signals of climate change — cause myriad public health concerns, from the acute and direct (e.g., natural disasters like flooding and heat waves) to the indirect yet equally devastating (e.g., respiratory and mental illnesses). While impacts like these are observable and well documented, existing research has not established a direct link between climate change and life ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Lifestyle medicine experts call meaning, purpose, and spirituality foundational to evidence-based, whole-person lifestyle change

Significant acceleration of global warming since 2015

FAU awarded $2.4M NIH grant to study immune signaling and social behavior

Deep learning-enabled virtual multiplexed immunostaining of label-free tissue for vascular invasion assessment

New PET imaging study reveals how ketamine relieves treatment-resistant depression

New study reveals differences between anime bamboo muzzle and actual bamboo

The ‘Great Texas Freeze’ killed thousands of purple martins; biologists worry recovery could take decades

Cancer has a unique nuclear metabolic fingerprint

Tiny thermometers offer on-chip temperature monitoring for processors

New compound stops common complications after intestinal surgery

Breaking through water treatment limits with defect-free, high-efficiency next-generation ceramic filters!

Researchers determine structural motifs of water undecamer cluster

Researchers enhance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of covalent organic frameworks by constitutional isomer strategy

Molecular target drives immunogenicity in cancer immunotherapy

Plant cell structure could hold key to cancer therapies and improved crops

Sustainable hydrogen peroxide production: Breakthroughs in electrocatalyst design for on-site synthesis

Cash rewards for behavior change: A review of financial incentives science in one health contexts and implications

One Health antimicrobial resistance modelling: from science to policy

Artificial feeding platform transforms study of ticks and their diseases

Researchers uncover microscopic mechanism of alkali species dissolution in water clusters

Methionine restriction for cancer therapy: A comprehensive review of mechanisms and clinical applications

White House autism briefing linked to swift shifts in prescribing patterns, study finds

Specialist palliative care can save the NHS up to £8,000 per person and improves quality of life

New research warns charities against ‘AI shortcut’ to empathy

Cannabis compounds show promise in fighting fatty liver disease

Study in mice reveals the brain circuits behind why we help others

Online forum to explore how organic carbon amendments can improve soil health while storing carbon

Turning agricultural plastic waste into valuable chemicals with biochar catalysts

Hidden viral networks in soil microplastics may shape the future of sustainable agriculture

Americans don’t just fear driverless cars will crash — they fear mass job losses

[Press-News.org] Don’t look back: The aftermath of a distressing event is more memorable than the lead-up, study suggestsThe moments that follow a distressing episode are more memorable than the moments leading up to it.