(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY—A team of scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Columbia University has demonstrated a way to produce large quantities of the receptor that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, binds to on the surface of human cells. That binding between the now-infamous viral spike protein and the human “ACE2” receptor is the first step of infection by the virus. Making functional human ACE2 protein in mouse cells gives scientists a new way to study these receptors and potentially put them to use. In addition, as described in a paper just published in the journal Virology, the method could facilitate the study of other complex proteins that have proven difficult to produce by other means.

The Brookhaven scientists’ initial goal, early in the pandemic, was to make large amounts of human ACE2 and then attach the protein to nanoparticles. The ACE2-coated nanoparticles could then be tested as anti-viral therapeutics and/or as sensors for detecting virus particles.

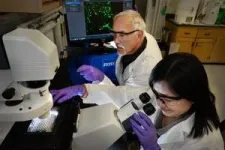

“For either of these applications, you need large quantities of protein, and the protein has to be fully functional,” said Brookhaven Lab virologist Paul Freimuth, who led the research in collaboration with scientists at Brookhaven Lab’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN). “But making functional membrane proteins like ACE2 is particularly challenging because the process by which proteins are localized in the cell membrane is complex.”

One reason is that these proteins are modified in various ways after they are synthesized and before they are inserted into the cell membrane. In particular, carbohydrate molecules added to the proteins play key roles in both how the long protein chain gets folded into its final 3D structure and how the protein functions in the membrane.

“Carbohydrates account for about one-third of the mass of ACE2 protein,” Freimuth said.

The simplest cells scientists use to generate proteins artificially, namely bacteria, lack the enzymes for attaching those carbohydrate add-ons. So, the Brookhaven team turned to cells from mice, which, as mammals, are more like us—and are thus able to do the same kind of carbohydrate processing. Mouse cells are known to be adept at picking up and expressing “foreign” genes. And while mouse cells also make an ACE2 receptor, the mouse version of the protein doesn’t bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike. That means the scientists would have an easy way to see if the mouse cells made the human ACE2 protein—by seeing if the spikes would bind to the cells.

Finding and expressing the ACE2 gene

To increase the chances that mouse cells would incorporate and read the human ACE2 gene correctly, the group used the intact gene. Genes from humans and other “higher organisms” contain lots of information in addition to the sequence of DNA that codes for the amino acid building blocks that make up a protein. This extra information helps to regulate gene structure and function within the cell’s chromosomes.

The scientists searched libraries of cloned DNA fragments that were generated as part of the Human Genome Project—a DOE-sponsored effort to map out the locations of all the genes that make us human—to find a fragment that contained the intact ACE2 gene, complete with its embedded regulatory information. Then, they exposed mouse cells to nanoparticles coated with this DNA fragment plus the gene for another protein that makes cells resistant to a lethal antibiotic.

“In this case, the nanoparticles serve as a DNA-delivery agent that gets engulfed by cells so the DNA can potentially become integrated into the mouse cell chromosomes,” Freimuth said. “To find the cells that picked up the foreign gene(s), we add the antibiotic to the cell cultures. Cells that failed to take up and express the antibiotic-resistance gene died, whereas those that acquired antibiotic resistance survived and grew into colonies.”

The scientists expanded about 50 of those colonies into individual cultures and then tested them to determine how many had also picked up the human ACE2 gene and produced the human receptor protein.

Detecting protein production

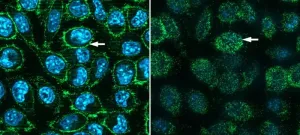

“About 70% of the antibiotic-resistant colonies expressed the human ACE2 protein on the cell surface,” Freimuth said. “Further analysis showed that these colonies contained, on average, 28 copies of the human ACE2 gene.”

Importantly, the mouse cells held onto the “foreign” ACE2 gene copies and kept making the human ACE2 protein encoded by these genes for at least 90 cell generations.

The level of human ACE2 protein produced by the cells was generally proportional to the number of ACE2 gene copies integrated into the mouse genome. Several of the mouse cell clones produced about 50 times more ACE2 than is normally present on mouse cells.

The scientists used a variety of methods to test whether the mouse-made human ACE2 proteins were functional. These included demonstrating that a “pseudovirus” containing the COVID spike protein—that is, a non-pathogenic stand-in for SARS-CoV-2—could bind to the receptors and infect the cells.

“These infectivity assays showed that the human ACE2 protein expressed on these mouse cells is fully functional,” Freimuth said.

Uses and implications

Meanwhile, Oleg Gang and Feiyue Teng, study co-authors from CFN, explored various ways to create extracellular nano-vesicles enriched with decoy human ACE2 for the potential treatment of COVID-19. They are also investigating the placement of ACE2 proteins onto nanoparticles for potential applications in infection treatment or rapid virus detection.

“The challenge posed by ACE2-based nano-vesicles lies in enhancing their neutralization effect against SARS-CoV-2. We are also looking for ways to enhance and leverage the binding sensitivity and specificity of ACE2-coupled nanoparticles to make them useful for virus diagnostics. Both approaches would require future optimization efforts,” said Teng, a research associate at CFN who worked extensively on both the biological aspects of this study and the potential nanoscience-based applications.

“We are excited to combine advances in nanomaterial fabrication with biomolecular approaches for developing new therapeutic and sensing strategies,” said Gang, who holds a joint appointment at Columbia University. “This study allowed us to overcome some methodological problems since nanomaterials and biosystems required quite different characterization approaches. What we have learned here is important for our next steps in enhancing nanoparticle-based biosensing.”

In addition to enabling possible applications of recombinant ACE2 protein, the work also demonstrates a novel approach for producing a wide range of complex proteins. Examples include the vast array of cell-surface receptors that mediate countless biological and disease processes, as well as industrially important proteins such as monoclonal antibodies and enzymes.

“Our method of using intact genes along with mouse cells that can be adapted to grow in huge suspension cultures—much like the liquid broth cultures used to grow bacteria—could advance the large-scale production of these and other important proteins,” Freimuth said.

This research was supported by a Laboratory Directed Research and Development grant and used resources of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. CFN is a DOE Office of Science user facility supported by the Office of Science (BES).

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

END

Scientists make COVID receptor protein in mouse cells

Initially motivated to make receptor-based sensors and therapies for COVID-19, scientists develop general strategy for producing other complex proteins

2024-01-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

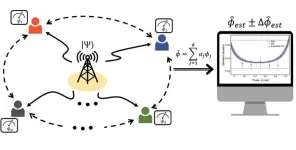

Researchers unveil new way to counter mobile phone ‘account takeover’ attacks

2024-01-22

Computer science researchers have developed a new way to identify security weaknesses that leave people vulnerable to account takeover attacks, where a hacker gains unauthorized access to online accounts.

Most mobiles are now home to a complex ecosystem of interconnected operating software and Apps, and as the connections between online services has increased, so have the possibilities for hackers to exploit the security weaknesses, often with disastrous consequences for their owner.

Dr Luca Arnaboldi, from the University of Birmingham’s School of Computer Science, explains: “The ruse of looking over someone’s shoulder to find out their PIN is well known. ...

What factors affect patients’ decisions regarding active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer?

2024-01-22

Because low-risk prostate cancer is unlikely to spread or impact survival, experts and guidelines recommend active surveillance, which involves regular monitoring and thus avoid or delay treatment like surgery or radiation therapy and their life-changing complications. A new study examined the rates of active surveillance use and evaluated the factors associated with selecting this management strategy over surgery or radiation, with a focus on underserved Black patients who have been underrepresented in prior studies. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

For the study, called the Treatment ...

New sustainable method for creating organic semiconductors

2024-01-22

Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, have developed a new, more environmentally friendly way to create conductive inks for use in organic electronics such as solar cells, artificial neurons, and soft sensors. The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, pave the way for future sustainable technology.

Organic electronics are on the rise as a complement and, in some cases, a replacement to traditional silicon-based electronics. Thanks to simple manufacturing, high flexibility, and low weight combined with the electrical properties typically associated with traditional semiconductors, it can be useful for applications such as digital displays, energy storage, ...

Digital dice and youth: 1 in 6 parents say they probably wouldn’t know if teens were betting online

2024-01-22

As young people increasingly have access and exposure to online gambling, only one in four parents say they have talked to their teen about some aspect of virtual betting, a national poll suggests.

But over half of parents aren’t aware of their state’s legal age for online gambling and one in six admit they probably wouldn’t know if their child was betting online, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health.

“Teens and young adults may have a difficult time going ...

Enable distributed quantum sensors for simultaneous measurements in distant places

2024-01-22

We've all had the experience of trying to get the exact time of a highly competitive concert ticket or class beforehand. If the time in Seoul and Busan is off by even a fraction of an hour, one will be less successful than the other. Sharing the exact time between distant locations is becoming increasingly important in all areas of our lives, including finance, telecommunications, security, and other fields that require improved accuracy and precision in sending and receiving data.

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) announced that Dr. Hyang-Tag Lim and his team at the Center ...

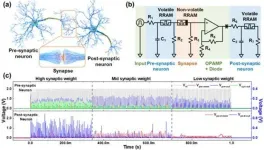

Implement artificial neural network hardware systems by stacking them like "neuron-synapse-neuron" structural blocks

2024-01-22

With the emergence of new industries such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and machine learning, the world's leading companies are focusing on developing next-generation artificial intelligence semiconductors that can process vast amounts of data while consuming energy efficiently. Neuromorphic computing, inspired by the human brain, is one of them. As a result, devices that mimic biological neurons and synapses are being developed one after another based on emerging materials and structures, but research on integrating individual devices into a system to verify and optimize them ...

The megalodon was less mega than previously believed

2024-01-22

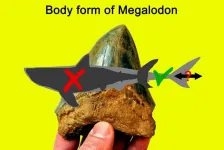

A new study shows the Megalodon, a gigantic shark that went extinct 3.6 million years ago, was more slender than earlier studies suggested. This finding changes scientists’ understanding of Megalodon behavior, ancient ocean life, and why the sharks went extinct.

The Megalodon or megatooth shark is typically portrayed as a super-sized monster in popular culture, with recent examples in the sci-fi films “The Meg” (2018) and “Meg 2: The Trench” (2023). Previous studies assume that the shark likely reached lengths of at least 50 feet and possibly as much as 65 feet.

However, the Megalodon is largely known only from its teeth and vertebrae in the ...

Slender shark: Study finds Megalodon was not like a gigantic great white shark

2024-01-22

CHICAGO — A new scientific study shows that the prehistoric gigantic shark, Megalodon or megatooth shark, which lived roughly 15-3.6 million years ago nearly worldwide, was a more slender shark than previous studies have suggested.

Formally called Otodus megalodon, it is typically portrayed as a super-sized, monstrous shark in novels and sci-fi films, including “The Meg.” Previous studies suggest the shark likely reached lengths of at least 50 to 65 feet (15 to 20 meters). However, ...

New criteria for sepsis in children based on organ dysfunction

2024-01-21

Clinician-scientists from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago were among a diverse, international group of experts tasked by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) with developing and validating new data-based criteria for sepsis in children. Sepsis is a major public heath burden, claiming the lives of over 3.3 million children worldwide every year. The new pediatric sepsis criteria – called the Phoenix criteria – follow the paradigm shift in the recent adult criteria that define sepsis as severe ...

Development and validation of the Phoenix criteria for pediatric sepsis and septic shock

2024-01-21

About The Study: In this international, multicenter, retrospective cohort study including more than 3.6 million pediatric encounters, a novel score, the Phoenix Sepsis Score, was derived and validated to predict mortality in children with suspected or confirmed infection. The new criteria for pediatric sepsis and septic shock based on the score performed better than existing organ dysfunction scores and the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference criteria.

Authors: Tellen D. Bennett, M.D., M.S., of the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, is the corresponding author.

To access the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New findings highlight two decades of evidence supporting pecans in heart-healthy diets

Case report explores potential link between mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and cancer

Healthy versions of low-carb and low-fat diets linked to better cardiovascular and metabolic health

Low-carb and low-fat diets associated with lower heart disease risk if rich in high-quality, plant-based foods, low in animal products

ASH publishes clinical practice guidelines on frontline and relapsed/refractory management of all in adolescents and young adults

City of Hope research spotlight, January 2026

Keeping an eagle eye on carbon stored in the ocean

FAU study: Tiny worm offers clues to combat chemotherapy neurotoxicity

The ACMG Foundation 2026 Early Career Travel Award is presented to Bianca Seminotti, Ph.D.

Rural cancer patients do just as well when having surgery close to home

New biosensor technology could improve glucose monitoring

Successful press conference for Special Issue II of the JSE Himalayas Series

Hair extensions contain many more dangerous chemicals than previously thought

Elevated lead levels could flow from some US drinking water kiosks

Fragile X study uncovers brainwave biomarker bridging humans and mice

Robots that can see around corners using radio signals and AI

A non-invasive therapeutic strategy for improving bone healing in aged patients

Molecule found to drive skin cancer growth and evade immune detection

Smokefree generation law could see English smoking prevalence drop below 5% decades earlier than expected

Heart disease risk factors appeared at younger age among South Asian adults in the U.S.

Paralysis treatment heals lab-grown human spinal cord organoids

US South Asians face elevated heart risk at age 45 despite healthier habits

DNA barcoding reveals the complexity of breast cancer liquid biopsies

Flagship whales facing climate-driven decline in Australia

Does a past abortion or miscarriage affect a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer?

Could a treatment redirect the body’s anti-viral immune response to target cancer cells?

How does universal, free prescription drug coverage affect older adults’ finances and behaviors?

Do certain factors affect life expectancy in people with spina bifida?

New study: Routine aspirin therapy prevents severe preeclampsia in at-risk populations

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

[Press-News.org] Scientists make COVID receptor protein in mouse cellsInitially motivated to make receptor-based sensors and therapies for COVID-19, scientists develop general strategy for producing other complex proteins