(Press-News.org) At the beginning of November, The New York Times ran the headline, “America is using up its groundwater like there’s no tomorrow.” The journalists from the renowned media outlet had published an investigation into the state of groundwater reserves in the United States. They came to the conclusion that the United States is pumping out too much groundwater.

But the US isn’t an isolated case. “The rest of the world is also squandering groundwater like there’s no tomorrow,” says Hansjörg Seybold, Senior Scientist in the Department of Environmental Systems Science at ETH Zurich. He is coauthor of a study that has just been published in the journal Nature.

Scientific evidence of rapidly depleting water resources

Together with researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), he has corroborated the journalists’ worrying findings. It is not only in North America that far too much groundwater is being pumped out, but also in other parts of the world where humans have settled.

In an unprecedented feat of painstaking effort, the researchers have compiled and analysed data from over 170,000 groundwater monitoring wells and 1,700 groundwater systems over the past 40 years.

This measurement data shows that in recent decades, humans have massively expanded groundwater extraction worldwide. The water level in most groundwater-bearing rock layers, known as aquifers, has fallen drastically almost everywhere in the world since 1980. And since 2000, this decline in groundwater reserves has accelerated. The effects are most pronounced in aquifers in the world’s arid regions, including California and the High Plains in the US, along with Spain, Iran, and Australia.

“We weren’t surprised that groundwater levels have fallen sharply worldwide, but we were shocked at how the pace has picked up in the past two decades,” Seybold says.

One of the reasons Seybold cites for the accelerated drop in groundwater levels in arid regions is that people use these areas intensively for agriculture and are pumping (too) much of the groundwater to the surface to irrigate crops, for example in California’s Central Valley.

Food cultivation and climate change exacerbate the problem

Moreover, the world’s population is growing, which means more food needs to be produced, for example in the arid regions of Iran. This is one of the countries where groundwater reserves have fallen the most.

But climate change is also exacerbating the groundwater crisis: some areas have become drier and hotter in recent decades, meaning agricultural crops need to be irrigated more heavily. Where climate change is driving a decline in precipitation, groundwater resources recover more slowly, if at all.

Heavy rainfall, which is occurring more frequently in some places as a result of climate change, is also not of any help. If the water comes in huge quantities, the soil often cannot absorb it. Instead, the water drains off at the surface without seeping into the groundwater. This problem is particularly acute in places with a high level of soil sealing, such as large cities.

Trend can be reversed

“The study also reveals good news,” says co-author Debra Perrone. “Aquifers in some areas have recovered in places where there have been policy changes or where alternative sources of water are available for direct use or for recharging the aquifer.”

One of the positive examples is the Genevese aquifer, which supplies drinking water to around 700,000 people in the canton of Geneva and the neighbouring French department of Haute-Savoie. Between 1960 and 1970, its level fell drastically because both Switzerland and France were pumping out water in an uncoordinated manner. Some wells even dried up and had to be closed.

To preserve the shared water resource, politicians and authorities in both countries agreed to replenish the aquifer artificially with water from the Arve River. The intention was first to stabilise the groundwater level and later to raise it – and the intervention was a success. “While the water level in this aquifer may not have returned to its original level, the example shows that groundwater levels don’t always have to go only one way: down,” Seybold says.

Other countries are reacting, too

The authorities have also had to take action in other countries: In Spain, a large pipeline has been built to carry water from the Pyrenees to central Spain, where it feeds the Los Arenales aquifer. In Arizona, water is diverted from the Colorado River into other bodies of water to replenish the groundwater reservoirs – although this does cause the delta of the Colorado River to dry up at times.

“Such examples are a ray of hope,” says UCSB researcher and lead author Scott Jasechko. Nevertheless, he and his colleagues are urgently calling for more measures to combat the depletion of groundwater supplies. “Once heavily depleted, aquifers in semi-deserts and deserts may require hundreds of years to recover because there’s simply not enough rainfall to swiftly replenish these aquifers,” Jasechko says.

There is an additional danger on the coasts: if the groundwater level falls below a certain level, seawater can invade the aquifer. This salinises the wells, leaving the water that is pumped up unusable neither for drinking water nor for irrigating fields; trees whose roots reach into the flow of groundwater die. On the east coast of the US, there are already extensive ghost forests with not a single living tree.

“That’s why we can’t put the problem on the back burner,” Seybold says. “The world must take urgent action.”

END

Groundwater levels are sinking ever faster around the world

2024-01-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

$1.2 million grant awarded to LSU LCMC Health Cancer Center to help break down barriers to cervical cancer prevention

2024-01-24

NEW ORLEANS (Jan. 24, 2024) – A research team from LSU LCMC Health Cancer Center has been awarded a $1.5 million grant to eliminate barriers from cervical cancer prevention. The five-year program combines a $1.2 million award from the American Cancer Society and $75,000 a year for five years investment from LSU Health New Orleans.

Louisiana has one of the highest cervical cancer death rates in the country. Cervical cancer rates are higher in predominantly African American communities represented in both urban (New Orleans) and rural areas of Louisiana. Black women in Louisiana are diagnosed with and die from cervical cancer at a significantly ...

Off-road autonomy: U-M's Automotive Research Center funded with $100 million through 2028

2024-01-24

Images

The U.S. Army has extended its long-running relationship with the University of Michigan's Automotive Research Center, reaching a new five-year, agreement of up to $100 million to boost work on autonomous vehicle technologies.

This potentially doubles the federal government's financial investment with ARC since the last agreement, reached in 2019. Following its 1994 launch, the ARC has served as a source of technology and first-in-class modeling and simulation for the Army's fleet of vehicles—the largest such fleet in the world.

"We are driving the development of modern mobility systems with our advanced modeling ...

Atmospheric pressure changes could be driving Mars’ elusive methane pulses

2024-01-24

New research shows that atmospheric pressure fluctuations that pull gases up from underground could be responsible for releasing subsurface methane into Mars’ atmosphere; knowing when and where to look for methane can help the Curiosity rover search for signs of life.

“Understanding Mars’ methane variations has been highlighted by NASA’s Curiosity team as the next key step towards figuring out where it comes from,” said John Ortiz, a graduate student at Los Alamos National Laboratory who led the research team. “There are several challenges associated with meeting that goal, ...

New pieces in the puzzle of first life on Earth

2024-01-24

Microorganisms were the first forms of life on our planet. The clues are written in 3.5 billion-year-old rocks by geochemical and morphological traces, such as chemical compounds or structures that these organisms left behind. However, it is still not clear when and where life originated on Earth and when a diversity of species developed in these early microbial communities. Evidence is scarce and often disputed. Now, researchers led by the University of Göttingen and Linnӕus University in Sweden have uncovered key findings about the earliest forms of life. In rock ...

Post pandemic, US cardiovascular death rate continues upward trajectory

2024-01-24

Ann Arbor, January 24, 2024 – New research confirms what public health leaders have been fearing: the significant uptick in the cardiovascular disease (CVD) death rate that began in 2020 has continued. The continuing trend reverses improvements achieved in the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce mortalities from heart disease and stroke, the leading causes of death in the United States. The findings are reported in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, published by Elsevier.

Investigators from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ...

New model predicts how shoe properties affect a runner’s performance

2024-01-24

A good shoe can make a huge difference for runners, from career marathoners to couch-to-5K first-timers. But every runner is unique, and a shoe that works for one might trip up another. Outside of trying on a rack of different designs, there’s no quick and easy way to know which shoe best suits a person’s particular running style.

MIT engineers are hoping to change that with a new model that predicts how certain shoe properties will affect a runner’s performance.

The simple model incorporates ...

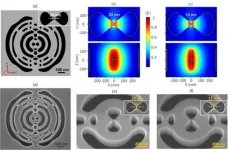

Sub-wavelength confinement of light demonstrated in indium phosphide nanocavity

2024-01-24

WASHINGTON — As we transition to a new era in computing, there is a need for new devices that integrate electronic and photonic functionalities at the nanoscale while enhancing the interaction between photons and electrons. In an important step toward fulfilling this need, researchers have developed a new III-V semiconductor nanocavity that confines light at levels below the so-called diffraction limit.

“Nanocavities with ultrasmall mode volumes hold great promise for improving a wide range of photonic ...

Laura M. Barzilai, JD, LLM, elected Chair of Board of Directors of the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR)

2024-01-24

NEW YORK— The American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), a national, nonprofit whose mission is to advance and support healthy aging through biomedical research, is pleased to announce the election of Laura M. Barzilai, JD, LLM, as Chair of the Board of Directors.

Stephanie Lederman, EdM, AFAR Executive Director, shares: "The Board of Directors of AFAR unanimously elected Laura Barzilai as Chair in December 2023. For nearly a decade, her contributions as a board member, committee chair, ...

Talking tomatoes: How their communication is influenced by enemies and friends

2024-01-24

Plants produce a range of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds that influence their interactions with the world around them. In a new study, researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign investigated how the type and amount of these VOCs change based on different features of tomato plants.

The smell of cut grass is one of the defining fragrances of summer. Smells like that are one of the ways plants signal their injury. Because they cannot run away from danger, plants have evolved to communicate with each other using chemical signals. They use VOCs for a ...

Thomas A. Rando, MD, PhD, elected President of the Board of Directors of the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR)

2024-01-24

The American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), a national, nonprofit whose mission is to advance and support healthy aging through biomedical research, is pleased to announce the election of Thomas A. Rando, MD, PhD, as President of the Board of Directors in December 2023.

Dr. Rando is currently the Director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Biology at UCLA, where he is a professor of Neurology and Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology. Previously, he ...