(Press-News.org) **EMBARGOED UNTIL 7:01 P.M. ET TUESDAY, JAN 30**

Evolutionary biologists at Johns Hopkins Medicine report they have combined PET scans of modern pigeons along with studies of dinosaur fossils to help answer an enduring question in biology: How did the brains of birds evolve to enable them to fly?

The answer, they say, appears to be an adaptive increase in the size of the cerebellum in some fossil vertebrates. The cerebellum is a brain region responsible for movement and motor control.

The research findings are published in the Jan. 31 issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Scientists have long thought that the cerebellum should be important in bird flight, but they lacked direct evidence. To pinpoint its value, the new research combined modern PET scan imaging data of ordinary pigeons with the fossil record, examining brain regions of birds during flight and braincases of ancient dinosaurs.

“Powered flight among vertebrates is a rare event in evolutionary history,” says Amy Balanoff, Ph.D., assistant professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and first author on the published research.

In fact, Balanoff says, just three groups of vertebrates, or animals with a backbone, evolved to fly: extinct pterosaurs, the terrors of the sky during the Mesozoic period, which ended over 65 million years ago, bats and birds.

The three species are not closely related on the evolutionary tree, and the key factors or factor that enabled flight in all three have remained unclear.

Besides the outward physical adaptations for flight, such as long upper limbs, certain kinds of feathers, a streamlined body and other features, Balanoff and her colleagues designed research to find features that created a flight-ready brain.

To do so, she worked with biomedical engineers at Stony Brook University in New York to compare the brain activity of modern pigeons before and after flight.

The researchers performed positron emission tomography, or PET, imaging scans, the same technology commonly used on humans, to compare activity in 26 regions of the brain when the bird was at rest and immediately after it flew for 10 minutes from one perch to another. They scanned eight birds on different days.

PET scans use a compound similar to glucose that can be tracked to where it’s most absorbed by brain cells, indicating increased use of energy and thus activity. The tracker degrades and gets excreted from the body within a day or two.

Of the 26 regions, one area — the cerebellum — had statistically significant increases in activity levels between resting and flying in all eight birds. Overall, the level of activity increase in the cerebellum differed by more than two standard statistical deviations, compared with other areas of the brain.

The researchers also detected increased brain activity in the so-called optic flow pathways, a network of brain cells that connect the retina in the eye to the cerebellum. These pathways process movement across the visual field.

Balanoff says their findings of activity increase in the cerebellum and optic flow pathways weren’t necessarily surprising, since the areas have been hypothesized to play a role in flight.

What was new in their research was linking the cerebellum findings of flight-enabled brains in modern birds to the fossil record that showed how the brains of birdlike dinosaurs began to develop brain conditions for powered flight.

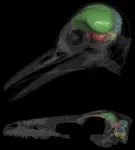

To do so, Balanoff used a digitized database of endocasts, or molds of the internal space of dinosaur skulls, which when filled, resemble the brain.

Balanoff identified and traced a sizable increase in cerebellum volume to some of the earliest species of maniraptoran dinosaurs, which preceded the first appearances of powered flight among ancient bird relatives, including Archaeopteryx, a winged dinosaur.

Balanoff and her team also found evidence in the endocasts of an increase in tissue folding in the cerebellum of early maniraptorans, an indication of increasing brain complexity.

The researchers cautioned that these are early findings, and brain activity changes during powered flight could also occur during other behaviors, such as gliding. They also note that their tests involved straightforward flying, without obstacles and with an easy flightpath, and other brain regions may be more active during complex flight maneuvers.

The research team plans next to pinpoint precise areas in the cerebellum that enable a flight-ready brain and the neural connections between these structures.

Scientific theories for why the brain gets bigger throughout evolutionary history include the need to traverse new and different landscapes, setting the stage for flight and other locomotive styles, says Gabriel Bever, Ph.D., associate professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“At Johns Hopkins, the biomedical community has a wide-ranging set of tools and technology to help us understand evolutionary history and link our findings to fundamental research on how the brain works,” he adds.

In addition to Balanoff and Bever, other authors of the study are Elizabeth Ferrer of the American Museum of Natural History and Samuel Merritt University; Lemise Saleh and Paul Vaska of Stony Brook University; Paul Gignac of the American Museum of Natural History and University of Arizona, M. Eugenia Gold of the American Museum of Natural History and Suffolk University; Jesús Marugán-Lobón of the Autonomous University of Madrid; Mark Norell of the American Museum of Natural History; David Ouellette of Weill Cornell Medical College; Michael Salerno of the University of Pennsylvania; Akinobu Watanabe of the American Museum of Natural History, New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Natural History Museum of London; and Shouyi Wei of the New York Proton Center.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Science Foundation.

END

Scientists pinpoint growth of brain’s cerebellum as key to evolution of bird flight

2024-01-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Machine learning informs a new tool to guide treatment for acute decompensated heart failure

2024-01-30

A recent study co-authored by Dr. Matthew Segar, a third-year cardiovascular disease fellow at The Texas Heart Institute and led by his research and residency mentor, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Dr. Ambarish Pandey, utilized a machine learning-based approach to identify, understand, and predict diuretic responsiveness in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

The study “A Phenomapping Tool and Clinical Score to Identify Low Diuretic Efficiency in Acute Decompensated ...

Clear legal rules about the use of sperm and eggs in fertility treatment must remain to protect the vulnerable, study says

2024-01-30

Clear legal rules outlining the use of the sperm and eggs of those who are incapacitated must remain in place to protect the vulnerable from being involved in fertility treatment without their consent, a new study says.

There are strict laws in England and Wales involving the use of reproductive materials, but the research outlines how recent court cases have weakened this existing rigorous consent regime.

It warns this could create a common law exception to informed consent, leaving the current law in a delicate position. The research says it is “not outside the realms of possibility” that some people may try to take ...

New interview with Eric Topol, MD, on the state of artificial intelligence in precision oncology

2024-01-30

An interview with Eric J. Topol, MD, a world-renowned cardiologist, best-selling author of several books on personalized medicine, and the founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, California, has been published. in the new peer-reviewed journal, AI in Precision Oncology. Dr. Topol is an advocate for using digital technologies and artificial intelligence in health care. click here to read the interview now.

Douglas Flora, MD, Editor-in-Chief of AI in Precision Oncology, interviewed Dr. ...

Rotman School Professor named to Thinkers50 Radar Class

2024-01-30

Rotman School Professor Named to Thinkers50 Radar Class

Toronto – Maja Djikic, an associate professor of organizational behaviour and human resource management at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, has been named to the Thinkers50 Radar class for 2024.

Announced every January, the Thinkers50 Radar identifies a cohort of 30 up-and-coming thinkers from around the world whose ideas have the potential to make an important impact on management thinking in the future.

A personality psychologist specializing in adult development, Prof. Djikic is executive director of the Self-Development Lab at the Rotman School, which provides ...

Researchers find early symptoms of psychosis spectrum disorder in youth higher than expected

2024-01-30

A new study co-led by Associate Professor Kristin Cleverley of the Lawrence Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing has found evidence that Psychosis Spectrum Symptoms (PSS) are often present in youth accessing mental health services.

From a profile of the initial 417 youth aged 11-24 participating in the study, 50 per cent were shown to meet the threshold for Psychosis Spectrum Symptoms, a number Cleverley says was higher than expected, meaning there is a large number of children with these symptoms accessing mental health services.

Cleverley, ...

Pitt receives new grant to improve opioid use disorder treatment

2024-01-30

PITTSBURGH – The University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy’s Program Evaluation and Research Unit (PERU) has received a five-year, $7.8 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to improve quality of care for patients with opioid use disorder across Pennsylvania.

The project will establish the Helping to End Addiction Long-term (HEALing) Measures Center at Pitt, which will focus on developing and implementing measurement-based care into 20 community opioid treatment programs across Pennsylvania with the goal of enhancing treatment ...

Researchers craft new way to make high-temperature superconductors – with a twist

2024-01-30

An international team that includes Rutgers University–New Brunswick scientists has developed a new method to make and manipulate a widely studied class of high-temperature superconductors.

This technique should pave the way for the creation of unusual forms of superconductivity in previously unattainable materials.

When cooled to a critical temperature, superconductors can conduct electricity without resistance or energy loss. These materials have intrigued physicists for decades because they can achieve a state of ...

Study suggests secret for getting teens to listen to unsolicited advice

2024-01-30

A new study may hold a secret for getting your teenager to listen to appreciate your unsolicited advice.

The University of California, Riverside, study, which included “emerging adults” — those in their late teens and early 20s — found teens will appreciate parents’ unsolicited advice, but only if the parent is supportive of their teens’ autonomy.

Parents support autonomy by providing clear guidelines for limitations and rules that will be enforced. They ...

Tech inefficiencies, piles of (electronic) paperwork, and increased patient volume contribute to burnout of primary care physicians, study finds

2024-01-30

Burnout is an occupational phenomenon that results from chronic workplace stress, according to the World Health Organization. Burnout often includes emotional exhaustion, negative feelings or mental distance from one’s job, and a low sense of accomplishment at work. COVID-19 increased feelings of burnout in primary care physicians, and a new study, sought to understand primary care clinicians’ perspectives on burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic, the causes of burnout, and strategies to improve clinician well-being.

Inefficiencies of electronic health records systems and high levels of documentation contribute ...

XRCC1: A potential prognostic and immunological biomarker in low-grade gliomas

2024-01-30

“We conducted a comprehensive investigation into the potential of XRCC1 as a valuable diagnostic and prognostic indicator in diverse cancer types.”

BUFFALO, NY- January 30, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 1, entitled, “XRCC1: a potential prognostic and immunological biomarker in LGG based on systematic pan-cancer analysis.”

X-ray repair cross-complementation ...