(Press-News.org) The 1 million-square-mile Tibetan Plateau — often called the “roof of the world” — is the highest landmass in the world, averaging 14,000 feet in altitude. Despite the extreme environment, humans have been permanent inhabitants there since prehistoric times.

Farming and herding play major roles in the economy of the Tibetan Plateau today — as they have throughout history. To make the most of a difficult environment, farmers, agropastoralists and mobile herders interact and move in conjunction with one another, which in turn shapes the overall economy and cultural geography of the plateau.

A new study by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and Sichuan University in China, published Feb. 2 in Scientific Reports, traces the roots of the longstanding cultural interactions across the Tibetan Plateau to prehistoric times, as early as the Bronze Age.

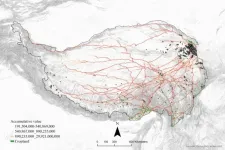

The researchers used advanced geospatial modeling to compare environmental and archaeological evidence that connects ancient mobility and subsistence strategies to cultural connections forged among farmers and herders in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Their findings show that these strategies influenced the settlement pattern and the transfer of ceramic styles — such as the materials used, characteristics and decorative features of the pottery — among distant prehistoric communities across the plateau.

The research was an enormous undertaking made possible thanks to advances in geospatial data analysis and high-resolution remote sensing, according to Michael Frachetti, a professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences at WashU and corresponding author of the study.

First, the researchers generated simulations of the optimal pathways of mobility used by prehistoric farmers and herders based on land cover and capacity of the environment to support the needs of their crops or herds. For example, highland herders typically move across zones with rich grass resources toward the more limited arable niches on the plateau. Repeated patterns emerging from these simulations were shown to statistically correlate with the geographic location of thousands of prehistoric sites across the Tibetan Plateau.

To test how these routes may have affected social interaction, the team compiled a large database of published archaeological findings from Bronze and Iron Age sites throughout Tibet and generated a social network based on shared technologies and designs of the ceramics found in these sites. The resulting social network suggests that even distant sites were well connected and in communication thousands of years ago across the Tibetan landmass.

“When we overlay the mobility maps with the social network, we see a strong correlation between routes for subsistence-oriented mobility and strong ties in material culture between regional communities, suggesting the emergence of ‘mobility highways’ over centuries of use,” Frachetti said. “This not only tells us that people were moving according to needs for farming and herding — which was largely influenced by environmental potential — but that mobility was key for building social relationships and the regional character of ancient communities on the Tibetan Plateau.”

Their findings also revealed an interesting caveat: The western part of Tibet did not match these patterns as well as the east. According to the authors, this suggests an alternative cultural orientation toward Central Asia, where similar mobility patterns connected prehistoric communities to the west. These east/west differences have been observed in other archaeological studies, they said.

“Archaeologists have been seeking to understand how and why ancient human communities build social relationships and cultural identities across the extreme terrain in Tibet for decades,” said lead author Xinzhou Chen, who earned his doctorate from WashU in 2023 and now works at the Center for Archaeological Sciences at Sichuan University. “This research provides a new perspective to explore the formation of human social cohesion in archaeology.”

END

Prehistoric mobility among Tibetan farmers, herders shaped highland settlement patterns, cultural interaction, study finds

2024-02-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

World Wetlands Day: Bogs hold an important key to the climate crisis

2024-02-02

World Wetlands Day: Bogs hold an important key to the climate crisis

Peat bogs store twice as much CO2 as all of the world's forests combined. A new research center at the University of Copenhagen will map Earth’s wetlands and provide important knowledge about the greenhouse gas budgets of these areas. The Global Wetland Center will teach us how to contain carbon from plants and trees in bogs and other wetlands – and preserve it as well as the ancient bog bodies also found there.

He is world-renowned ...

Natural therapy shows promise for dry-eye disease

2024-02-02

Researchers at the University of Auckland are running a trial of castor oil as a potential safe and natural treatment for dry-eye disease following a successful pilot study.

While exact figures aren’t available for New Zealand, in Australia, it is estimated dry-eye disease affects around 58 percent of the population aged over 50.

Advancing age, menopause, increased screen time, contact lens wear are just some of the risk factors for developing dry eye disease.

Blepharitis is the most common cause of dry-eye disease, accounting for more than 80 percent of cases. It is a chronic condition with no known cure.

“Currently, patients ...

Researchers study role of post-transcriptional splicing in plant response to light

2024-02-02

In a study recently published in the PNAS on Jan. 30, a research team led by Prof. CAO Xiaofeng from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with researchers from the Southern University of Science and Technology, reported a new understanding of how light affects plant growth.

Light plays a central role in plant growth and development, providing an energy source and governing various aspects of plant morphology. Post-transcriptional splicing (PTS) has been previously discovered to generate polyadenylated full-length transcripts. These transcripts, ...

Gene-editing offers hope for people with hereditary disorder

2024-02-02

A group of patients with a hereditary disorder have had their lives transformed by a single treatment of a breakthrough gene-editing therapy, according to the lead researcher.

The patients from New Zealand, the Netherlands and the UK have hereditary angioedema, a genetic disorder characterised by severe, painful and unpredictable swelling attacks. These interfere with daily life and can affect airways and prove fatal.

Now researchers from the University of Auckland, Amsterdam University Medical Center and Cambridge University Hospitals have successfully treated more than ten patients with the CRISPR/Cas9 therapy, ...

New molecule from University step closer to treatment for rare disease

2024-02-02

A molecule created at the University of Auckland is one step closer to becoming a treatment for an extremely rare and severely debilitating neurological disorder called Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Children with the disorder showed significant improvements in a phase two clinical trial in the US, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, which is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, said in December.

Next steps would be a phase three trial and seeking approval from the US Food & Drug Administration. The molecule, NNZ-2591, comes from work years ago ...

Machine learning to battle COVID-19 bacterial co-infection

2024-02-02

University of Queensland researchers have used machine learning to help predict the risk of secondary bacterial infections in hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

The machine learning technique can help detect whether antibiotic use is critical for patients with these infections.

Associate Professor Kirsty Short from the School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences said secondary bacterial infections can be extremely dangerous for those hospitalised with COVID-19.

“Estimates of the incidents of secondary bacterial infections in COVID-19 ...

Some tumors ‘grow bad’: Why a dangerous subtype of Wilms tumor is so resistant to chemotherapy

2024-02-02

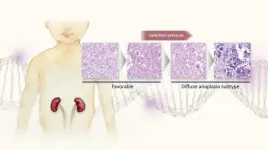

An international team, led by researchers at Nagoya University in Japan, may have determined why the diffuse anaplasia (DA) subtype of Wilms tumor (WT) resists chemotherapy. This subtype grows even when it has a high burden of DNA damage and increases the mutation rate of tumor protein 53 (TP53), a gene that plays a critical role in the regulation of cell growth and division. The team’s findings, published in Modern Pathology, suggest new ways to treat this subtype.

WT, also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common childhood cancer originating in the kidney. Fortunately, the survival rate of adolescents ...

Disrupted cellular function behind type 2 diabetes in obesity

2024-02-02

Disrupted function of “cleaning cells” in the body may help to explain why some people with obesity develop type 2 diabetes, while others do not. A study from the University of Gothenburg describes this newly discovered mechanism.

It is well known that obesity increases the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. It is also well known that some people who gain weight suffer from the disease and others do not. The reasons for these differences are not clear, but they are related ...

USC launches School of Advanced Computing

2024-02-02

USC President Carol Folt launched the university’s first new school in more than a decade: the USC School of Advanced Computing, a cornerstone of her $1 billion advanced computing initiative. The school seeks to educate all students, regardless of their major, in the ethical use of computing technology as part of the president’s Frontiers of Computing initiative.

Gaurav Sukhatme — a professor of computer science and electrical and computer engineering, and executive vice dean of the USC Viterbi School of ...

A clutch stretch goes a long way

2024-02-02

Kyoto, Japan -- Cell biology has possibly never jumped to the next level in the same way.

In multicellular organisms, cell migration and mechanosensing are essential for cellular development and maintenance. These processes rely on talin, the key focal adhesion -- or FA -- protein, central in connecting adjacent cellular matrices and enabling force transmission between them.

Talins are commonly considered fully extended at FAs between actin filaments -- or F-actin -- and the anchor-like integrin receptor.

Yet, a research ...