(Press-News.org) Who hasn't seen it before: the view through the microscope in which a sperm penetrates an egg cell and fertilises it. This fundamental step in procreation happens dynamically and seemingly without problems. However, if you zoom in on the processes that take place during fertilisation at a molecular level, it becomes highly complex and it is thus not surprising that 15 percent of couples worldwide struggle to conceive. No microscope, however modern, can illuminate the countless interactions between the proteins involved. Therefore, the exact trigger for the fertilisation process and the molecular events that transpire just before the fusion of the sperm and egg have remained murky — until now.

With the help of simulations on "Piz Daint", the supercomputer of the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), a research team led by ETH Zurich Professor, Viola Vogel has now made the dynamics of these crucial processes in the fertilisation of a human egg cell visible for the first time. According to their study, which was recently published in the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers’ simulations have succeeded in revealing important secrets.

Special protein complex enables the fusion process

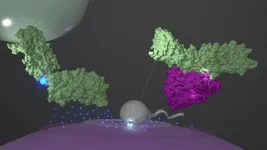

It was previously known that the first specific physical connection between the two germ cells is an interaction of two proteins: the JUNO, which is located on the outer membrane of the female egg cell, and the IZUMO1 on the surface of the male sperm cell. "It was assumed that the combination of the two proteins into a complex initiates the recognition and adhesion process between the germ cells, thereby enabling their fusion," says Paulina Pacak, a postdoctoral researcher in Vogel's group and first author of the study. However, based on the crystal structure scientists had not yet been able to clearly describe the mechanism.

The ETH research team finally succeeded in doing this in their latest simulations. In order to create a realistic environment in the in-silico experiment, the researchers needed to simulate JUNO and IZUMO1 in an aqueous solution. In water, however, the protein moves, and the interactions with the water molecules change both the way the proteins bind to each other and, in some cases, the function of the proteins themselves. "This makes the simulations much more complex, also because water alone already has a highly complex structure," says Vogel, "but the simulations provide a more detailed picture of the dynamic of the interactions."

The simulations on "Piz Daint" spanned 200 nanoseconds each and showed that the JUNO-IZUMO1 complex is stabilised by a network of over 30 short-lived contacts — the individual bonds lasted less than 50 nanoseconds each. According to the researchers, a deeper understanding of these network dynamics of the rapidly changing formation and breaking of individual bonds presents new possibilities for the development of contraceptives, as well as for better understanding mutations that affect fertility.

Zinc ions regulate bond strength

With these network dynamics brought to light, the researchers then investigated how these vital protein binding could be destabilised. Zinc ions (Zn2+) play an important role here: If they are present, IZUMO1 bends into a boomerang-like structure as shown by the simulations and, as a result, IZUMO1 can no longer firmly bind to the JUNO protein. According to the researchers, this could be one reason why the egg cell releases many zinc ions immediately after fertilisation in a so-called "zinc spark". This flood of zinc is known to prevent further sperm from penetrating the egg cell which would otherwise cause aberrant development.

"We can only find out something like this with the help of simulations. The findings that we derive from them would hardly be possible on the basis of the static crystal structures of the proteins," emphasises Vogel. "The highly dynamic process of fertilisation takes place far away from the equilibrium. As available protein structures show them embedded in the crystal, resources such as those at CSCS are essential to capture and understand these interaction dynamics."

Folic acid binding by IZUMO1

Thanks to the simulations, the researchers were able to unravel another mystery too: how naturally occurring folates and their synthetic equivalents, folic acids, bind to the JUNO protein. Expectant mothers are generally recommended to take folic acid supplements before a planned pregnancy and during the first three months to support healthy neural development in the fetus. However, laboratory experiments have shown that the JUNO protein does not bind with folate in aqueous solution, even though JUNO itself is a folate receptor. The molecular dynamics simulations have now shown that Folate binding is possible once IZUMO1 binds to JUNO. Only then can the folate enter the presumed folate-binding pocket of JUNO.

These new discoveries are not only of fundamental interest for structural biology. They also provide a detailed basis for the development of active pharmaceutical ingredients. According to the researchers, the decoded dynamic mechanisms of the interaction between the JUNO and IZUMO1 proteins could point to new ways of treating infertility, developing drug-based non-hormonal contraceptive methods, and improving in vitro fertilisation technology.

END

Scientists successfully simulate protein complex that initiates fertilization

2024-02-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Immune cells lose ‘killer instinct’ in cancerous tumors – but functionality can be re-awakened

2024-02-02

Some immune cells in our bodies see their ‘killer instinct’ restricted after entering solid tumours, according to new research.

In a new paper published in Nature Communications, a team led by researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Cambridge found how immune cells called natural killer cells (NK cells) rapidly lose their functionality when entering and residing in tumours.

Using tumour cells grown from mice models, the team established that NK cells adopt a dormant state when entering solid tumours through the loss of production of key effector mechanisms used to promote immune ...

Did climate change trigger pandemics in antiquity?

2024-02-02

For their study in Science Advances, the researchers reconstructed temperatures and precipitation for the period from 200 BC to 600 AD, with a resolution of three years. This means that two data points cover a period of three years – an extremely high resolution for paleoclimate researchers. The period extends from the so-called Roman Climatic Optimum to the Late Antique Little Ice Age. This period also includes three major pandemics known from historians’ records: the Antonine Plague (around 165 to 180 AD), the Cyprian Plague (around 251 to 266) and the Justinian ...

Outstanding success in the Excellence Strategy: TU Dresden enters the next round with three new Clusters of Excellence initiatives

2024-02-02

As a result, TUD ranks second overall in the number of calls for proposals in the current competition nationwide. This is according to today’s joint announcement (February 2, 2024) by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the German Science and Humanities Council (WR). An international panel of experts appointed by the DFG and the WR through the Joint Science Conference (GWK) has assessed a total of 143 draft proposals over the last few days and selected 41 as valuable funding opportunities.

In addition, TUD's three existing Clusters of Excellence have expressed their intent to the DFG that they wish to continue their outstanding research work. TUD, therefore, ...

HMSOM researchers: Data shows clinical trials becoming more inclusive

2024-02-02

Clinical trials and medical research have been historically lacking in diversity among all groups.

But recent trends have been turning the tide at least a little bit toward equity and inclusivity, according to a new meta-analysis published by a team of investigators from the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine (HMSOM) and the Hackensack Meridian Health Research Institute (HMHRI).

The meta-analysis of clinical trials which included New Jersey patients from 2017 to 2022 show a snapshot of more diverse representation - and better reporting of race and ethnicity factors, according to the new paper in the Elsevier ...

CAR T cells show promise against age-related diseases in mice

2024-02-02

Highlights

Laboratory research led by MSK and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory demonstrates the potential for CAR T cells to improve “healthspan” by eliminating senescent cells associated with aging-related diseases.

Not only was the treatment able to improve the metabolic function of aging mice and mice fed a high-fat diet, but it also proved protective against metabolic decline when given to younger mice.

The CAR T cell-based approach offers a powerful alternative to more traditional small-molecule drugs target senescent cells, supported by its long-lasting effects and the potential to fine-tune ...

Clinique partners with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to establish the Mount Sinai-Clinique Healthy Skin Dermatology Center

2024-02-02

New York, NY (February 2, 2024) – Clinique and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai today announced a philanthropic partnership to establish the Mount Sinai-Clinique Healthy Skin Dermatology Center. The Center will develop forward-thinking research in dermatology, exploring the biological underpinnings of how skin ages, skin allergies and inflammatory or eczematous skin conditions, including eczema (or atopic dermatitis) and contact dermatitis. Rooted in a shared mission to conduct dermatological research that improves patients’ lives, the partnership will focus on applicable scientific discovery and leading-edge innovation to modernize allergy science in order to ...

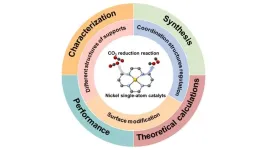

Strategies for enhancing the performance of nickel single-atom catalysts for the electroreduction of CO2 to CO

2024-02-02

Electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) is considered as an effective strategy for mitigating the energy crisis and the greenhouse effect. Among the multiple reduction products, CO is regarded as having the highest market value as it is a crucial feedstock for Fischer-Tropsch process which can synthesize high-value long-chain hydrocarbons. Since the carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR) has complex intermediates and multiple proton-coupled electron transfer processes, improving the reaction activity and products selectivity remain two great challenges.

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have the advantages of high atom utilization, tunable coordination structure ...

Brexit-induced spatial restrictions reveal alarming increase of fishing fleet’s carbon footprint

2024-02-02

In a study published today in Marine Policy, researchers have unveiled striking evidence that fisheries management decisions such as spatial fisheries restrictions can increase greenhouse gas emissions. The study, conducted by a team of scientists led by postdoctoral researcher Kim Scherrer at the University of Bergen, sheds light on the unforeseen consequences of policy changes on fishing fleets and their carbon footprint.

In the North Atlantic, international agreements often allow fleets to follow the fish across national borders. This allows fishers to catch the fish where it is most efficient. But when the UK left the EU (Brexit), ...

Scammed! Animals ‘led by the nose’ to leave plants alone

2024-02-02

University of Sydney researchers have shown it is possible to shield plants from the hungry maws of herbivorous mammals by fooling them with the smell of a variety they typically avoid.

Findings from the study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution show tree seedlings planted next to the decoy smell solution were 20 times less likely to be eaten by animals.

“This is equivalent to the seedlings being surrounded by actual plants that are unpalatable to the herbivore. In most cases it does trick the animals into leaving the plants alone,” said PhD student Patrick ...

Why are people climate change deniers?

2024-02-02

Do climate change deniers bend the facts to avoid having to modify their environmentally harmful behavior? Researchers from the University of Bonn and the Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) ran an online experiment involving 4,000 US adults, and found no evidence to support this idea. The authors of the study were themselves surprised by the results. Whether they are good or bad news for the fight against global heating remains to be seen. The study is being published in the journal Nature Climate Change. STRICTLY EMBARGOED: Do not publish before Friday, February 02, 11 a.m. CET!

A surprisingly large number of people ...