(Press-News.org) University of Sydney researchers have shown it is possible to shield plants from the hungry maws of herbivorous mammals by fooling them with the smell of a variety they typically avoid.

Findings from the study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution show tree seedlings planted next to the decoy smell solution were 20 times less likely to be eaten by animals.

“This is equivalent to the seedlings being surrounded by actual plants that are unpalatable to the herbivore. In most cases it does trick the animals into leaving the plants alone,” said PhD student Patrick Finnerty, the study’s lead author from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences Behavioural Ecology and Conservation Lab.

“Herbivores cause significant damage to valuable plants in ecological and economically sensitive areas worldwide, but killing the animals to protect the plants can be unethical,” he said.

“So, we created artificial odours that mimicked the smell of plant species they naturally avoid, and this gently nudged problematic herbivores away from areas we didn’t want them to be.

“Given that many herbivores use plant odour as their primary sense to forage, this method provides a new approach that could be used to help protect valued plants globally, either in conservation work or protecting agricultural crops.”

The experiment, conducted in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Sydney, used the swamp wallaby as model herbivore. The researchers selected an unpalatable shrub in the citrus family, Boronia pinnata, and a palatable canopy species, Eucalyptus punctata, to test the concept.

The study compared using B. pinnata solution and the real plant and found both were equally successful at protecting eucalypt seedlings from being eaten by wallabies.

As part of his doctoral research, Mr Finnerty has also tested the method successfully with African elephants, but that fieldwork does not form part of this research paper.

Previous attempts to use repellent substances, such as chilli oil or motor oil, to control animal consumption of plants have inherent limitations, Mr Finnerty said.

“Animals tend to habituate to these unnatural cues and so deterrent effects are only temporary,” he said. “By contrast, by mimicking the smell of plants herbivore naturally encounter, and avoid in day-to-day foraging, our approach works with the natural motivators of these animals, with herbivores less likely to habituate to these smells.”

Researchers took this idea and used solutions that produce these undesired aromas.

“As a management tool to protect palatable plants, our technique offers many advantages over real plants as a repellent,” Mr Finnerty said. “Real plants compete for water and resources, which can outweigh protective effects in providing browsing refuge.

“Our approach should be transferable to any mammalian, or potentially invertebrate, herbivore that relies primarily on plant odour information to forage and could protect valued plants globally, such as threatened species.”

Current solutions to herbivore-related problems often involve costly and environmentally impactful measures such as lethal control or fencing.

The new research introduces an alternative low-cost, humane strategy based on understanding herbivores’ foraging cues, motivations and decisions.

“Plant browsing damage caused by mammalian herbivore populations like deer, elephants and wallabies is a growing global concern,” said senior study author Professor Clare McArthur.

“This damage is one of the greatest limiting factors in areas of post-fire recovery and revegetation, destroying more than half the seedlings in these areas. It also threatens endangered plants and causes billions of dollars of damage in forestry and agriculture globally.

“Current methods to protect plants are expensive and increasingly limited by concerns over animal welfare, so alternate approaches are needed.”

Research: ‘Olfactory misinformation provides refuge to palatable plants from mammalian browsing’, Finnerty, et al (Nature Ecology & Evolution). DOI: 0.1038/s41559-024-02330-x

Download photos of the researcher, wallabies in the experiment set-up and video and photographs of fieldwork with elephants at this link.

AVAILABLE FOR INTERVIEW

Patrick Finnerty | patrick.finnerty@sydney.edu.au | +61 498 102 984

Professor Clare McArthur | clare.mcarthur@sydney.edu.au

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Marcus Strom | marcus.strom@sydney.edu.au | +61 474 269 459

Declaration: The authors declare no competing interests. The research was funded by the Ecological Soceity of Australia, Australian Academy of Science, Royal Zoological Society of Australia, Australian Wildlife Society, NSW Department of Planning and Environment, and the Australian Research Council.

The research was funded by the Ecological Soceity of Australia, Australian Academy of Science, Royal Zoological Society of Australia, Australian Wildlife Society, NSW Department of Planning and Environment, and the Australian Research Council.

END

Scammed! Animals ‘led by the nose’ to leave plants alone

Tested on swamp wallabies, the method looks like it also works with African elephants

2024-02-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Why are people climate change deniers?

2024-02-02

Do climate change deniers bend the facts to avoid having to modify their environmentally harmful behavior? Researchers from the University of Bonn and the Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) ran an online experiment involving 4,000 US adults, and found no evidence to support this idea. The authors of the study were themselves surprised by the results. Whether they are good or bad news for the fight against global heating remains to be seen. The study is being published in the journal Nature Climate Change. STRICTLY EMBARGOED: Do not publish before Friday, February 02, 11 a.m. CET!

A surprisingly large number of people ...

Epigenetic status determines metastasis

2024-02-02

Scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and Heidelberg University investigated in mice how spreading tumor cells behave at the site of metastasis: Some tumor cells immediately start to form metastases. Others leave the blood vessel and may then enter a long period of dormancy. What determines which path the cancer cells take is their epigenetic status. This was also confirmed in experiments with human tumor cells. The results of the study could pave the way for novel diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

What makes cancer so dangerous? ...

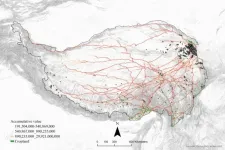

Prehistoric mobility among Tibetan farmers, herders shaped highland settlement patterns, cultural interaction, study finds

2024-02-02

The 1 million-square-mile Tibetan Plateau — often called the “roof of the world” — is the highest landmass in the world, averaging 14,000 feet in altitude. Despite the extreme environment, humans have been permanent inhabitants there since prehistoric times.

Farming and herding play major roles in the economy of the Tibetan Plateau today — as they have throughout history. To make the most of a difficult environment, farmers, agropastoralists and mobile herders interact and move in conjunction with one another, which in turn shapes ...

World Wetlands Day: Bogs hold an important key to the climate crisis

2024-02-02

World Wetlands Day: Bogs hold an important key to the climate crisis

Peat bogs store twice as much CO2 as all of the world's forests combined. A new research center at the University of Copenhagen will map Earth’s wetlands and provide important knowledge about the greenhouse gas budgets of these areas. The Global Wetland Center will teach us how to contain carbon from plants and trees in bogs and other wetlands – and preserve it as well as the ancient bog bodies also found there.

He is world-renowned ...

Natural therapy shows promise for dry-eye disease

2024-02-02

Researchers at the University of Auckland are running a trial of castor oil as a potential safe and natural treatment for dry-eye disease following a successful pilot study.

While exact figures aren’t available for New Zealand, in Australia, it is estimated dry-eye disease affects around 58 percent of the population aged over 50.

Advancing age, menopause, increased screen time, contact lens wear are just some of the risk factors for developing dry eye disease.

Blepharitis is the most common cause of dry-eye disease, accounting for more than 80 percent of cases. It is a chronic condition with no known cure.

“Currently, patients ...

Researchers study role of post-transcriptional splicing in plant response to light

2024-02-02

In a study recently published in the PNAS on Jan. 30, a research team led by Prof. CAO Xiaofeng from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with researchers from the Southern University of Science and Technology, reported a new understanding of how light affects plant growth.

Light plays a central role in plant growth and development, providing an energy source and governing various aspects of plant morphology. Post-transcriptional splicing (PTS) has been previously discovered to generate polyadenylated full-length transcripts. These transcripts, ...

Gene-editing offers hope for people with hereditary disorder

2024-02-02

A group of patients with a hereditary disorder have had their lives transformed by a single treatment of a breakthrough gene-editing therapy, according to the lead researcher.

The patients from New Zealand, the Netherlands and the UK have hereditary angioedema, a genetic disorder characterised by severe, painful and unpredictable swelling attacks. These interfere with daily life and can affect airways and prove fatal.

Now researchers from the University of Auckland, Amsterdam University Medical Center and Cambridge University Hospitals have successfully treated more than ten patients with the CRISPR/Cas9 therapy, ...

New molecule from University step closer to treatment for rare disease

2024-02-02

A molecule created at the University of Auckland is one step closer to becoming a treatment for an extremely rare and severely debilitating neurological disorder called Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Children with the disorder showed significant improvements in a phase two clinical trial in the US, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, which is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, said in December.

Next steps would be a phase three trial and seeking approval from the US Food & Drug Administration. The molecule, NNZ-2591, comes from work years ago ...

Machine learning to battle COVID-19 bacterial co-infection

2024-02-02

University of Queensland researchers have used machine learning to help predict the risk of secondary bacterial infections in hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

The machine learning technique can help detect whether antibiotic use is critical for patients with these infections.

Associate Professor Kirsty Short from the School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences said secondary bacterial infections can be extremely dangerous for those hospitalised with COVID-19.

“Estimates of the incidents of secondary bacterial infections in COVID-19 ...

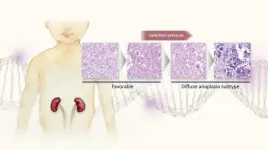

Some tumors ‘grow bad’: Why a dangerous subtype of Wilms tumor is so resistant to chemotherapy

2024-02-02

An international team, led by researchers at Nagoya University in Japan, may have determined why the diffuse anaplasia (DA) subtype of Wilms tumor (WT) resists chemotherapy. This subtype grows even when it has a high burden of DNA damage and increases the mutation rate of tumor protein 53 (TP53), a gene that plays a critical role in the regulation of cell growth and division. The team’s findings, published in Modern Pathology, suggest new ways to treat this subtype.

WT, also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common childhood cancer originating in the kidney. Fortunately, the survival rate of adolescents ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

Researchers visualize the dynamics of myelin swellings

Cheops discovers late bloomer from another era

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

New-onset nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and initiators of semaglutide in US veterans with type 2 diabetes

Availability of higher-level neonatal care in rural and urban US hospitals

Researchers identify brain circuit and cells that link prior experiences to appetite

Frog love songs and the sounds of climate change

Hunter-gatherers northwestern Europe adopted farming from migrant women, study reveals

Light-based sensor detects early molecular signs of cancer in the blood

3D MIR technique guides precision treatment of kids’ heart conditions

Which childhood abuse survivors are at elevated risk of depression? New study provides important clues

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

[Press-News.org] Scammed! Animals ‘led by the nose’ to leave plants aloneTested on swamp wallabies, the method looks like it also works with African elephants