(Press-News.org) New Haven, Conn. — A Yale-led research team has picked a side in the “Snowball Earth” debate over the possible cause of planet-wide deep freeze events that occurred in the distant past.

According to a new study, these so-called “Snowball” Earth periods, in which the planet’s surface was covered in ice for thousands or even millions of years, could have been triggered abruptly by large asteroids that slammed into the Earth.

The findings, detailed in the journal Science Advances, may answer a question that has stumped scientists for decades about some of the most dramatic known climate shifts in Earth’s history. In addition to Yale, the study included researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Vienna.

Climate modelers have known since the 1960s that if the Earth became sufficiently cold, the high reflectivity of its snow and ice could create a “runaway” feedback loop that would create more sea ice and colder temperatures until the planet was covered in ice. Such conditions occurred at least twice during Earth’s Neoproterozoic era, 720 to 635 million years ago.

Yet efforts to explain what initiated these periods of global glaciation, which have come to be known as “Snowball Earth” events, have been inconclusive. Most theories have centered on the notion that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere somehow declined to a point where “snowballing” began.

“We decided to explore an alternative possibility,” said lead author Minmin Fu, the Richard Foster Flint Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “What if an extraterrestrial impact caused this climate change transition very abruptly?”

For the study, the researchers used a sophisticated climate model that represents atmospheric and ocean circulation, as well as the formation of sea ice, under different conditions. It is the same type of climate model that is used to predict future climate scenarios.

In this instance, the researchers applied their model to the aftermath of a hypothetical asteroid strike in four distinct periods of the past: preindustrial (150 years ago), Last Glacial Maximum (21,000 years ago), Cretaceous (145 to 66 million years ago), and Neoproterozoic (1 billion to 542 million years ago).

For two of the warmer climate scenarios (Cretaceous and preindustrial), the researchers found that it was unlikely that an asteroid strike could trigger global glaciation. But for the Last Glacial Maximum and Neoproterozoic scenarios, when the Earth’s temperature may have been already cold enough to be considered an ice age — an asteroid strike could have tipped Earth into a “Snowball” state.

“What surprised me most in our results is that, given sufficiently cold initial climate conditions, a ‘Snowball’ state after an asteroid impact can develop over the global ocean in a matter of just one decade,” said co-author Alexey Fedorov, a professor of ocean and atmospheric sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “By then the thickness of sea ice at the Equator would reach about 10 meters. This should be compared to a typical sea ice thickness of one to three meters in the modern Arctic.”

As for the chances of an asteroid-induced “Snowball Earth” period in the years to come, the researchers said it was unlikely — due in part to human-caused warming that has heated the planet — even though other impacts could be as devastating.

The research was supported by the Flint Postdoctoral Fellowship at Yale and the ARCHANGE project. Co-authors of the study are Dorian Abbot of the University of Chicago and Christian Koeberl of the University of Vienna.

END

Yale joins the ‘Snowball’ fight over global deep freeze periods

2024-02-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sensors made from ‘frozen smoke’ can detect toxic formaldehyde in homes and offices

2024-02-09

Researchers have developed a sensor made from ‘frozen smoke’ that uses artificial intelligence techniques to detect formaldehyde in real time at concentrations as low as eight parts per billion, far beyond the sensitivity of most indoor air quality sensors.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, developed sensors made from highly porous materials known as aerogels. By precisely engineering the shape of the holes in the aerogels, the sensors were able to detect the fingerprint of formaldehyde, a common indoor air pollutant, at room temperature.

The proof-of-concept sensors, which require minimal power, could be adapted to detect ...

University Hospitals now offering FDA-approved medication for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

2024-02-09

CLEVELAND—University Hospitals (UH) Brain Health & Memory Center is now treating patients with LEQEMBI® (lecanemab), a Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Those with Alzheimer’s disease often have an abnormal buildup of plaques in their brain that contain a protein called beta-amyloid,” said Charles J. Duffy, MD, PhD, neurologist and Director of the Brain Health & Memory Center within the UH Neurological Institute. “Lecanemab ...

Unlocking quantum precision: Expanded superconducting strips for enhanced photon-counting accuracy

2024-02-09

Using single photons as qubits has become a prominent strategy in quantum information technology. Accurately determining the number of photons is crucial in various quantum systems, including quantum computation, quantum communication, and quantum metrology. Photon-number-resolving detectors (PNRDs) play a vital role in achieving this accuracy and have two main performance indicators: resolving fidelity, which measures the probability of accurately recording the number of incident photons, and dynamic range, which describes the maximum resolvable photon number.

Superconducting nanostrip single-photon detectors (SNSPDs) are considered the leading ...

From growing roots, clues to how stem cells decide their fate

2024-02-09

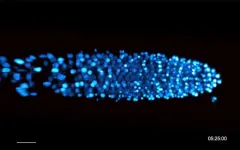

DURHAM, N.C. -- It might look like a comet or a shooting star, but this time-lapse video is actually a tiny plant root, not much thicker than a human hair, magnified hundreds of times as it grows under the microscope.

Researchers at Duke University have been making such movies by peering at stem cells near the root’s tip and taking snapshots as they divide and multiply over time, using a technique called light sheet microscopy.

The work offers more than a front row seat to the drama of growing roots. By watching how the cells divide in response to certain chemical signals, the team is finding new clues to how stem cells choose one ...

UK's Nursing’s Stanifer chosen as scholar in Environmental Health Research Institute for Nurse and Clinician Scientists

2024-02-09

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Feb. 8, 2024) — A researcher in the University of Kentucky College of Nursing has been selected as a scholar for the Environmental Health Research Institute for Nurse and Clinician Scientists (EHRI-NCS).

EHRI-NCS is a year-long flipped classroom, train-the-trainer and mentorship program aimed at developing a new era of environmental health nursing science. It’s led by Castner Incorporated, a health research company, in partnership with Emory University, Washington State University and University of Alabama in Huntsville.

Stacy Stanifer, Ph.D., an advanced practice registered nurse and an assistant professor of nursing, was selected to participate. ...

Protein accumulation on fat droplets implicated in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

2024-02-09

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – UNC School of Medicine researcher Sarah Cohen, PhD, and Ian Windham, a former PhD student from the Cohen lab, have made a new discovery about apolipoprotein E (APOE) – the biggest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Older people who inherited a genetic variant called APOE4 from their parents have a two- or three-times greater risk of developing the late-onset neurodegenerative disease. If researchers can better understand how APOE4 is affecting brain cells, it may help them design effective therapeutics and target the mechanisms causing the enhanced disease risk.

Cohen and Windham performed an exceptionally ...

New strategy for safer CAR T cell therapy in lymphomas

2024-02-09

In the treatment of aggressive lymphomas and blood cancer (leukaemia), so-called chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T cells) are increasingly being used. For this therapy, immune cells are taken from patients and programmed by means of genetic engineering to detect proteins on the malignant tumour cells. Back in the body, the CAR T cells then fight the cancer cells. Due to some heavy side effects, this therapy requires extreme caution and long hospital stays. Scientists at University Hospital Cologne are therefore researching ...

Mariana Mesel-Lemoine appointed as Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the Institut Pasteur

2024-02-09

Acting on a proposal from the Institut Pasteur President Yasmine Belkaid, the Institut Pasteur Board of Governors appointed Mariana Mesel-Lemoine as Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion on Wednesday February 7, 2024.

This appointment marks a significant milestone in the history of the Institut Pasteur, and it is the first French research institute to establish a position of this kind at such a senior and strategic level. Mariana Mesel-Lemoine will report directly to the President. Her mission will be to propose policy and strategy priorities related to diversity, equity and inclusion for the "Pasteur 2030" Strategic Plan, to oversee ...

Time to anticoagulation reversal and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage

2024-02-09

About The Study: In hospitals participating in Get With The Guidelines–Stroke, earlier anticoagulation reversal was associated with improved survival for patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. These findings support intensive efforts to accelerate evaluation and treatment for patients with this devastating form of stroke.

Authors: Kevin N. Sheth, M.D., of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

Data shows significant prevalence of sleep apnea among cardio-oncology patients

2024-02-09

Sleep apnea is prevalent among cardio-oncology patients who are at higher risk for congestive heart failure from cancer therapy, according to a new study being presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Advancing the Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient course.

Sleep apnea is a disorder of altered breathing while asleep with two types, obstructive (OSA) or central (CSA). Both can be treated to alleviate symptoms and improve cardiovascular outcomes. This study pertains to obstructive sleep apnea. A well-established screening tool for detecting sleep apnea is the STOP-BANG questionnaire utilizing eight questions using ...