(Press-News.org) Living organisms often create what is needed for life from scratch.

For humans, this process means the creation of most essential compounds needed to survive. But not every living thing has this capability, such as the parasite that causes malaria, which affected an estimated 249 million people in 2022.

Virginia Tech researchers in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences found that by preventing the malaria parasite from scavenging fatty acids, a type of required nutrient, it could no longer grow.

“The key to this breakthrough is that we were able to develop a screening method for the malaria parasite and block this process,” said Michael Klemba, associate professor of biochemistry and principal investigator on the project. “While very much in its infancy, the results could open the door to a new way to fight malaria.”

Malaria is caused while the parasite is replicating in human red blood cell and it relies on scavenging, rather than creating, to satisfy its need for fatty acids. Many fatty acids are obtained by metabolizing a class of host lipid, called lysophospholipids. However, scientists didn't know how the parasite releases fatty acids from the host lipids.

The Virginia Tech research team did experiments with infected red blood cells and found chemicals that can stop the parasite from getting the needed fatty acids. Researchers discovered that two enzymes were instrumental in breaking down host lipids to release the fatty acids the parasite needs. These enzymes work in different places: One works outside in the red blood cell, and the other works inside the parasite.

When scientists removed these two enzymes, they found that the parasite struggled to get the needed fatty acids and couldn't grow well. This was especially true when that host lipid was the only fatty acid source available. When both enzymes were stopped from working, either by changing the parasite's genes or by using drugs, the parasites couldn't grow in human blood.

This shows that breaking down the host lipid, called lysophosphatidylcholine, to get fatty acids is critical for the malaria parasite's survival in our bodies and that targeting these two enzymes could be a new way to fight malaria.

The research was published today by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America and was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant, United States Department of Agriculture Hatch funding, and through the Department of Biochemistry at Virginia Tech.

Laying the groundwork

In 2017, a study came out that showed when lysophosphatidic acid levels drop in the host that the malaria parasite, known as Plasmodium falciparum, converts into a form that can be taken up by mosquitoes. P. falciparum causes malaria while replicating in host erythrocytes, or red blood cells, and relies on scavenging rather than synthesis, or the creation of compounds, to satisfy its need for fatty acids.

This seemed to be an important environmental cue, Klemba said, and that there was also evidence that host lipids were a preferred source of fatty acids.

“There wasn't clarity on what the metabolic pathways were,” he said. “If we could show that that these metabolic pathways were useful, then that would be an important contribution to the field.”

For Klemba, this was an important question to answer and one that his lab – and students – were in a unique position to do. Two graduate students worked on the project - Jiapeng Liu ’23, now a postdoctoral scholar at Rutgers University, and Christie Dapper, a former professor at Virginia Tech. Liu was the lead author and Katherine Fike assisted with the project as a research specialist.

“There are two enzymes that are really important for this process: one is inside the parasite, and the other is exported into the host cell,” Klemba said. “Which is not typical of metabolic processes as they are typically carried out within the parasite. Why did the parasite find it useful to put one of these enzymes into the host? We have some ideas that that could be involved in host modification, which could be that the parasite remodels the red cell once it's once it's set up shop.”

The researchers found that only removing one of the two enzymes, which they named XL2 and XLH4, doesn’t do anything. Both have to be removed to inhibit parasitic growth.

Future work

There are some limitations of the discovery: The research was conducted only using a culture dish, commonly referred to as in vitro. The researchers also are not sure if the compounds used to inhibit the two enzymes are toxic.

Some level of toxicity is expected, Klemba explained, and it may be possible to engineer the toxicity out of the compounds.

“But that could be a major challenge,” he said.

In the meantime, this discovery could open the door to therapeutic treatments for malaria.

END

Virginia Tech researchers discover that blocking an essential nutrient inhibits malaria parasite growth

The four-year study could lead to a new way to fight malaria, one of the most devastating infectious diseases in the world.

2024-02-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Children's Hospital Los Angeles researchers uncover social and economic factors that influence acute liver failure in children—and ways to overcome them

2024-02-13

Imagine your healthy child gets sick—so sick that you take them to the emergency department. You are shocked to find out that their liver is failing, and they will need a transplant to survive. Studies show that their chances of survival are higher the faster they can get to a hospital that performs liver transplants. But what factors affect how quickly that happens?

Pediatric acute liver failure, also called PALF, is a life-threatening condition that emerges with very little warning in previously healthy children. It is rare, affecting about 5,000 children in the United States a year, and can result from viral ...

Uncovering insights about prostate cancer risk and genetic ancestry

2024-02-13

This study included larger groups of people from African, Hispanic and Asian ancestries than many other previous studies.

A recent study involving scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory has uncovered insights into the prostate cancer risks of people from a variety of genetic ancestries. The project, which was led by the University of Southern California, included large increases in representation among men of African, Hispanic and Asian ancestries, that were contributed in part by an ongoing collaboration between the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and DOE as ...

A century of reforestation helped keep the eastern US cool

2024-02-13

American Geophysical Union

13 February 2024

AGU Release No. 24-5

For Immediate Release

This press release and accompanying multimedia are available online at: https://news.agu.org/press-release/a-century-of-reforestation-helped-keep-the-eastern-us-cool/

A century of reforestation helped keep the eastern US cool

Much of the U.S. warmed during the 20th century, but the eastern part of the country remained mysteriously cool. The recovery of forests could explain why

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, news@agu.org (UTC-5 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Kim ...

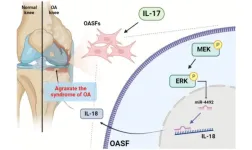

IL-17 promotes IL-18 production in osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts via…

2024-02-13

“This study provides novel insights into the pathogenesis of OA and suggests a potential therapeutic target in OA treatment.”

BUFFALO, NY- February 13, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 2, entitled, “IL-17 promotes IL-18 production via the MEK/ERK/miR-4492 axis in osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts.”

The concept of osteoarthritis (OA) as a low-grade inflammatory ...

New data speed record on optical fiber

2024-02-13

As data traffic continues to increase, there is a critical need for miniaturized optical transmitters and receivers that operate with high-order multi-level modulation formats and faster data transmission rates. In an important step toward fulfilling this requirement, researchers developed a new compact indium phosphide (InP)-based coherent driver modulator (CDM) and showed that it can achieve a record high baud rate and transmission capacity per wavelength compared to other CDMs. CDMs are optical transmitters used in optical communication systems that can put information on light by modulating the amplitude and phase before it is transmitted through optical fiber.

“Services that require ...

UBCO researchers get to the bottom of non-invasive gut tests

2024-02-13

New research from UBC Okanagan could make monitoring gut health easier and less painful by tapping into a common—yet often overlooked—source of information: the mucus in our digestive system that eventually becomes part of fecal matter.

Correct, what’s in our poop.

Researcher Dr. Kirk Bergstrom and post-graduate student Noah Fancy of UBCO's Biology department discovered a non-invasive technique to study MUC2, a critical gut protein, from what we leave behind in the bathroom.

“MUC2 is like the silent star in our guts. It’s constantly working ...

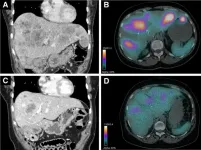

Radiopharmaceutical therapy controls symptoms and reduces medications in insulinoma patients

2024-02-13

Reston, VA—Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) is effective for clinical control of symptomatic metastatic insulinomas, according to new research published in the February issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. In the largest study to date of metastatic insulinoma patients treated with PRRT, more than 80 percent of patients had long-lasting symptom control, and nearly 60 percent were able to reduce the use of other drugs to treat the disease.

Metastatic insulinoma is a rare malignant neuroendocrine tumor characterized ...

First-of-its-kind ACC registry tracks cardiac procedures performed in ambulatory surgical settings

2024-02-13

The American College of Cardiology’s newest registry offers data-driven insights on cardiac procedures performed in the ambulatory surgery setting through its first-of-its-kind dashboard. The number of cardiac procedures being performed in ambulatory surgery centers has grown significantly in the last decade, leading ACC’s NCDR to create the CV ASC Registry Suite to fit into the established workflow and allow these facilities to measure and compare their patient care and outcomes to similar procedures performed in the hospital outpatient setting.

Ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) are health care facilities that provide same-day surgical care, ...

Business operations affect fishermen's resilience to climate change, new study finds

2024-02-13

Timothy Frawley has spent the better of the past two decades working in and around commercial fisheries. Born and raised in Casco Bay, Maine, he grew up packing lobsters and pitching bait on Portland’s working waterfront. He has worked in commercial fisheries in California, Alaska and the Mexican state of Baja California Sur.

Throughout his years spent on working waterfronts, Frawley, a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, closely observed the ways in which fishermen conducted their business, making decisions about what and how they fished, and how it affected their operations and profit.

“While ...

Not too late to repair: gene therapy improves advanced heart failure in animal model

2024-02-13

Heart failure remains the leading cause of mortality in the U.S. During a heart attack blood stops flowing into the heart. Without oxygen, part of the heart muscle dies. The heart muscle does not regenerate, instead it replaces dead tissue with a scar made of cells called fibroblasts that do not help the heart pump. If there is too much scarring, the heart progressively enlarges, or dilates, weakens and eventually stops working.

“The current thought is that advanced or chronic heart failure, a stage in which the cardiac muscle has become too weak, is a point of no return. The present ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Start school later, sleep longer, learn better

Many nations underestimate greenhouse emissions from wastewater systems, but the lapse is fixable

The Lancet: New weight loss pill leads to greater blood sugar control and weight loss for people with diabetes than current oral GLP-1, phase 3 trial finds

Pediatric investigation study highlights two-way association between teen fitness and confidence

Researchers develop cognitive tool kit enabling early Alzheimer's detection in Mandarin Chinese

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

[Press-News.org] Virginia Tech researchers discover that blocking an essential nutrient inhibits malaria parasite growthThe four-year study could lead to a new way to fight malaria, one of the most devastating infectious diseases in the world.